Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-02-06

Date: 2023-10-24

Date: 2023-10-06

|

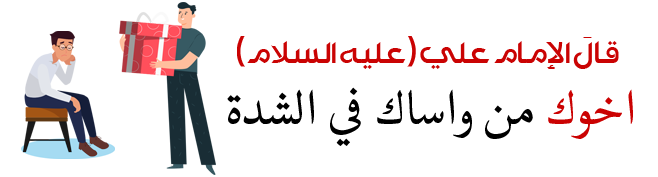

You might wonder why English has so little inflection. In fact, if you study the history of English, you’ll find that at one time English had quite a bit more inflection than it now has. The earliest form of English, Old English, was spoken from about 450 to 1100 CE. Old English had three genders – masculine, feminine, and neuter – and a case system with four cases – nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive, see (31). Articles and adjectives agreed with nouns in case and number, as (32) shows:

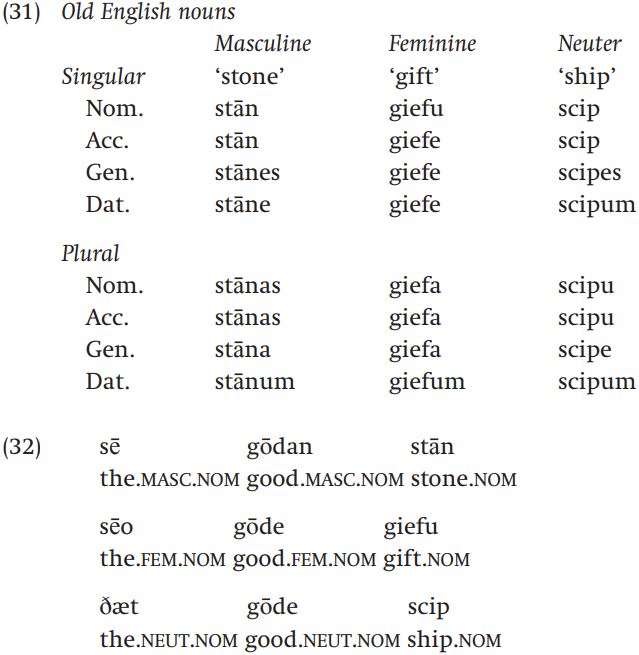

Verb inflection was also more complex in Old English than in Modern English. In Old English, verbs were inflected for person and number, and were different for present tense and past tense in both the indicative and the subjunctive. In addition, some verbs were strong verbs, which means that they show internal stem change – specifically ablaut – in some forms. For example, in the strong verb drīfan ‘to drive’ the present tense always has a long [i] vowel, but the past has the vowel [a] in the first and third person singular and a short [i] in the plural form and the second person singular. Other verbs were called weak verbs; these inflected using suffixes rather than ablaut. As you can see with the weak verb dēman ‘to judge’ in (33), the vowel of the stem never changes, but in the past tense there is always a suffix -d(e):

Why did English lose all this inflection? There are probably two reasons. The first one has to do with the stress system of English: in Old English, unlike modern English, stress was typically on the first syllable of the word. Ends of words were less prominent, and therefore tended to be pronounced less distinctly than beginnings of words, so inflectional suffixes tended not to be emphasized. Over time this led to a weakening of the inflectional system. But this alone probably wouldn’t have resulted in the nearly complete loss of inflectional marking that is the situation in present day English; after all, German – a language closely related to English – also shows stress on the initial syllables of words, and nevertheless has not lost most of its inflection over the centuries.

Some scholars attribute the loss of inflection to language contact in the northern parts of Britain. For some centuries during the Old English period, northern parts of Britain were occupied by the Danes, who were speakers of Old Norse. Old Norse is closely related to Old English, with a similar system of four cases, masculine, feminine, and neuter genders, and so on. The actual inflectional endings, however, were different, although the two languages shared a fair number of lexical stems. For example, the stem bōt meant ‘remedy’ in both languages, and the nominative singular in both languages was the same. But the nominative plural in Old English was bōta and in Old Norse bótaR. 2 The form bóta happened to be the genitive plural in Old Norse. Some scholars hypothesize that speakers of Old English and Old Norse could communicate with each other to some extent, but the inflectional endings caused confusion, and therefore came to be de-emphasized or dropped. One piece of evidence for this hypothesis is that inflection appears to have been lost much earlier in the northern parts of Britain where Old Norse speakers cohabited with Old English speakers, than in the southern parts of Britain, which were not exposed to Old Norse. Inflectional loss spread from north to south, until all parts of Britain were eventually equally poor in inflection.

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|