Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-06-14

Date: 2023-09-26

Date: 2023-11-14

|

Inflection versus derivation revisited

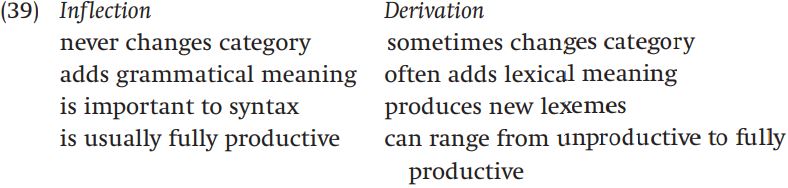

We have now looked in some detail both at inflection and at derivation (or lexeme formation, more generally). Remember that we distinguished the two sorts of morphology in the following ways:

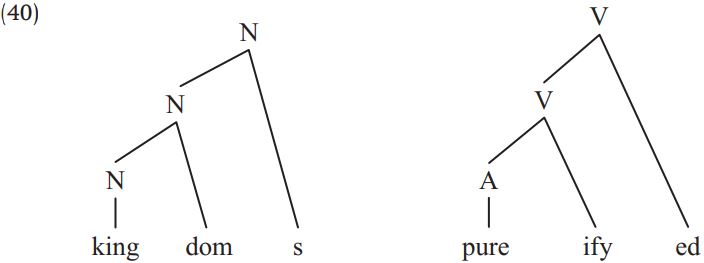

One more thing we can add to these differences is that in words that have both inflectional and derivational affixes, the derivational affixes almost always occur inside the inflectional ones. Remember that words are formed like onions, with successive layers added one by one. In these word structures, derivational affixes go closer to the base (or root or stem) than inflectional affixes do. For example, in English we can have words like kingdoms where the noun suffix -dom attaches to its base before the plural suffix -s, or purified where the verbforming suffix -ify attaches to the adjective pure before the past tense suffix -ed is added:

It’s not possible in English to attach a plural or past tense suffix and then a derivational suffix; we never form words like *kingsdom or *walkeder.

We’ve seen that the differences between inflection and derivation are usually quite clear, in terms of function, meaning, and position in word structures. In most cases, when we look at the morphology of languages it’s not too hard to distinguish inflection from derivation. There are cases, however, where the distinction doesn’t seem so clear-cut. One puzzling case is that of nouns in the West Atlantic language Fula . . Each noun in Fula belongs to up to seven different noun classes. One of those classes is a singular class, another a plural class, and the remainder are classes for singular and plural diminutives, pejorative diminutives (meaning something like ‘nasty little X’), augmentatives, and pejorative augmentatives. The various noun class forms for ‘monkey’ are shown in (41):

As (41) illustrates, noun class is marked in Fula not only by different suffixes, but also by mutation of the initial consonant of the noun stem. So in class 11, for example, the initial consonant of the stem is a continuant [w], in classes 25, 3, and 5, the initial consonant is a stop [b] that corresponds in point of articulation to the continuant, and in classes 6, 7, and 8 it is a prenasalized stop [mb], again corresponding in point of articulation. Singular and plural, of course, are number distinctions, and thus belong to the realm of inflection. Augmentatives and diminutives, however, are expressive morphology (look back to chapter 3, section 2), and are usually considered derivational. The whole list in (41) has the look of a paradigm, though, and even more perplexing, adjectives and articles agree with Fula nouns, even in the noun classes that form augmentatives and diminutives. Agreement, of course, is a hallmark of inflection. The point here is that it’s not at all clear in the case of Fula whether to count augmentatives and diminutives as inflectional or derivational, or just to concede that in this particular case the distinction just doesn’t make sense.

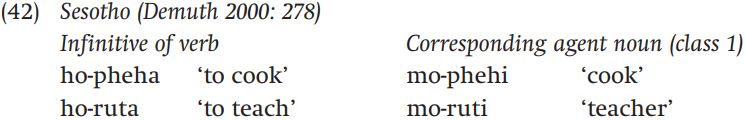

An equally perplexing case can be found in the Bantu language Sesotho. Like Fula, Sesotho has noun classes. Classes 1 and 2 are classes that contain human nouns. Interestingly, agent nouns can be derived from verbs by putting them into classes 1/2:

Formation of agent nouns from verbs certainly looks like derivation. Yet in Sesotho, as in Fula, articles and adjectives must agree with the nouns they modify, in that they must bear the class prefixes corresponding to those nouns. And agreement, of course, is part of inflection

We leave this issue unresolved here – although it may not seem particularly satisfying to a beginning student of morphology to know that the distinction between inflection and derivation is not always crystal clear, it is precisely cases like these that most intrigue morphologists!

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|