Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-02-15

Date: 4-2-2022

Date: 2023-10-02

|

We focus here on constructions in clauses. Two ideas are central to our discussion. The first is that we can recognize basic clauses and more complex clauses and can work out the relationships between them. That is, constructions are not isolated structures but fit into a general network.

The second idea is that different constructions exist, or have been created by the speakers and writers of given languages, to enable speakers and writers to signal what they are doing with a particular utterance. This connection between different constructions and different acts performed by speakers and writers is also central in the discussion of meaning and word classes. We first examine a number of different constructions in English and then consider the question of the relationships among them.

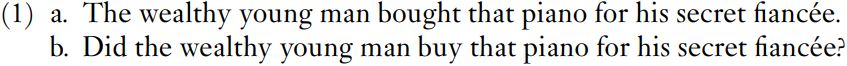

Consider the examples in (1).

Example (1a) and (1b) are clearly related. They are related semantically in that they both have to do with a situation in which one person, a wealthy young man, bought something, a piano, for another person, his secret fiancée. Both examples place that situation at some point in past time, and both present the event as completed. The young man completed the purchase of the piano, whereas was buying that piano would have left it open whether the purchase was completed or not. The semantic relationship is indicated by three properties of the examples. They share the major lexical items, wealthy, young, man, buy, piano, secret and fiancée; in both examples, wealthy and young modify man and secret modifies fiancée; and buy has as its complements the wealthy young man, referring to the buyer, that piano, referring to the thing bought, and his secret fiancée, referring to the recipient of the piano. Note that although (1a) contains bought and (1b) contains buy these are both forms of one and same lexical item.

Example (1a) and (1b) are clearly related. They are related semantically in that they both have to do with a situation in which one person, a wealthy young man, bought something, a piano, for another person, his secret fiancée. Both examples place that situation at some point in past time, and both present the event as completed. The young man completed the purchase of the piano, whereas was buying that piano would have left it open whether the purchase was completed or not. The semantic relationship is indicated by three properties of the examples. They share the major lexical items, wealthy, young, man, buy, piano, secret and fiancée; in both examples, wealthy and young modify man and secret modifies fiancée; and buy has as its complements the wealthy young man, referring to the buyer, that piano, referring to the thing bought, and his secret fiancée, referring to the recipient of the piano. Note that although (1a) contains bought and (1b) contains buy these are both forms of one and same lexical item.

Both examples share past tense, which is marked on bought in (1a) and on did in (1b). The two examples differ in that (1b) has did at the beginning of the clause while (1a) does not. The presence or absence of did is immaterial for the semantics as discussed so far because it has no effect on the type of event – buying, on the participants involved in the event, on whether the event is presented as completed or on the time of the event. The presence or absence of did at the front of the clause signals a difference in the speaker’s or writer’s attitude to the event; (1a) is used in order to assert or declare that the event took place, while (1b) is used in order to ask if the event did take place. (We ignore the various nuances of meaning that can be signaled in spoken language by changes in intonation and stress and that might signaled in writing by the use of italics or bold or underlining.)

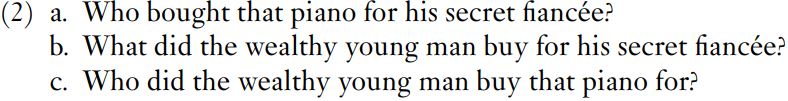

Example (1a) is an instance of a declarative construction (reflecting the idea that the speaker or writer declares something to be the case); (1b) is an example of an interrogative construction, used by speakers who wish to ask whether the event took place, that is, speakers who wish to interrogate the person or persons they are addressing (their addressees). Other interrogative constructions are used when speakers know that a particular type of event took place but not the identity of one or more participants. Consider the examples in (2).

Examples (2a–c) are not directly related in meaning to (1a–b), for the simple reason that (1a–b) specify all the participants in the buying event – the wealthy young man, the piano and the secret fiancée. In (2a–c), one of the participants is unknown. It makes more sense to consider (2a) as related in meaning to Someone bought a piano for his secret fiancée and (2b) as related in meaning to The wealthy young man bought something for his secret fiancée. (Note that Someone bought that piano for his secret fiancée has the same general syntactic structure as (1a), namely a noun phrase – the wealthy young man in (1a), then the verb and then a prepositional phrase for his secret fiancée.) The syntactic changes are slightly more complex. Where the identity of the buyer is requested, as in (2a), the noun phrase someone is replaced by who. Where the identity of another participant is requested, someone is replaced by who and something is replaced by what. Who and what move to the front of the clause, and did is inserted into the clause just following who or what.

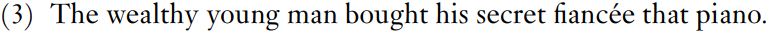

Returning to (1a), we see that other constructions are related to it (more accurately, to the construction exemplified in it). Consider (3).

What has changed is that the preposition for is missing and that piano has swapped places with his secret fiancée. Example (3) might be used when the fiancée has already been mentioned and the piano is being introduced into the conversation; (1a) is more likely to be used when the piano has already been mentioned and it is the fiancée who is being brought into the narrative. The semantic difference between these two constructions is minimal; the distinction has to do with which participant has already been mentioned and with which is being mentioned for the first time. The syntactic structure of (3) is the subject noun phrase the wealthy young man, followed by the verb bought, followed by the noun phrase his secret fiancée and finally the noun phrase that piano.

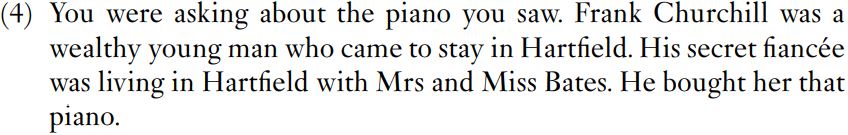

We can usefully note that (3) adds another factor to our view of language. We stated at the beginning of this chapter that different constructions have been developed by the speakers of languages to allow them to distinguish clearly between the different things they do with language – making assertions, asking questions and so on. Example (3) drives home a very important point; although it is convenient in textbooks such as this to take sentences and clauses one at a time, in real speech and writing they are accompanied by many other clauses and sentences. The choice of the construction in (3) is determined by what precedes it in a given conversation or letter, say. In fact, to make the example more realistic, we should change it to He bought her that piano; one of the enduring habits of speakers is that they introduce a participant into a narrative by means of a full noun phrase containing a noun and possibly an article and adjective and so on, but thereafter refer to that participant by means of a pronoun. We might have a text as in (4).

The fact that sentences are typically combined to create longer texts is why many manuals of languages include a selection of different texts in addition to the details of the morphology and syntax of a given language.

The fact that sentences are typically combined to create longer texts is why many manuals of languages include a selection of different texts in addition to the details of the morphology and syntax of a given language.

Utterance (1a) is an example of a declarative clause. It is also an example of an active clause, which contrasts with the corresponding passive clause in (5).

Why call this a ‘passive’ clause? The term ‘passive’ comes historically from the Latin verb patior (I suffer), or more exactly from its past participle, as in passus sum (having-suffered I-am, that is, ‘I have suffered’). This label was chosen for clauses in English and other languages which take as their starting point the participant on whom an action is carried out, that is, who suffers the action. In contrast, active clauses take as their starting point the participant who carries out an action, who is active in a given situation.

Why call this a ‘passive’ clause? The term ‘passive’ comes historically from the Latin verb patior (I suffer), or more exactly from its past participle, as in passus sum (having-suffered I-am, that is, ‘I have suffered’). This label was chosen for clauses in English and other languages which take as their starting point the participant on whom an action is carried out, that is, who suffers the action. In contrast, active clauses take as their starting point the participant who carries out an action, who is active in a given situation.

Notice two properties of passive clauses. First, the noun phrase referring to the passive participant, that piano in (5), is at the front of the clause and is in a special relationship with the verb (agreement in person and number. Second, although (5) does have a noun phrase, the wealthy young man, referring to the buyer, it can be omitted, as in That piano was bought for his secret fiancée. The construction in (5) is called the ‘long passive’ because it contains an agent noun phrase; but approximately 95 per cent of passive clauses in spoken and written texts do not have a phrase referring to the do-er or agent. Without its agent phrase, as in the above example That piano was bought for his secret fiancée, this construction is known as the ‘short passive’.

The final construction we look at is that of (6).

The clause in brackets provides a plausible context for the second clause. The speaker contrasts the two types of drink, producing a normal neutral clause to pass judgement on the plum juice and driving home the contrast by putting the direct object the juice at the front of the second clause. Not only does the second clause have an unusual construction, which in itself makes the message conspicuous, but the milk immediately follows the plum juice; the positioning of the two phrases right next to each other also highlights the contrast. As far as the syntactic structure is concerned, I just love the milk is a neutral main clause and the only change to the structure is that the phrase the milk moves to the beginning of the clause.

In the discussion of (3) above, we observed that, although we analyze clauses and sentences individually for convenience, in real language they do not occur in isolation but as part of longer texts. Constructions too can be and are analyzed in isolation because it is convenient to focus on one structure at a time; however, in a given language, constructions exist not in isolation but as part of a system of structures. We finish this by addressing the question ‘What is meant by “system”?’ and we do so on the basis of the six structures discussed above. To facilitate the discussion, the six structures are exemplified in (7) and (8) by means of simpler sentences.

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|