The lexicon Syntax and lexical items

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

47-5

الجزء والصفحة:

47-5

31-1-2022

31-1-2022

2843

2843

Syntax and lexical items

Syntax cannot be isolated from other areas of language; and individual lexical items, particularly verbs, exercise strong control over syntactic structure. We have already seen that when setting up word classes we have to appeal to syntactic criteria, to morphology and morpho-syntax and to meaning. We examined the idea that the head of a given phrase controls the other constituents in the phrase, and we saw immediately that there are different subclasses of nouns and verbs that impose different requirements on phrases and clauses. We saw only a small fraction of the extensive interplay between syntactic structure and individual lexical items; Again we can discuss only the main features, going into the topic in more detail but leaving huge areas untouched.

Analysts can isolate the syntactic constructions of a given language, as we started to do for English on constituent structure and on constructions. Syntactic constructions, however, are not identical with specific clauses; particular clauses do not appear until lexical items are inserted into a general syntactic structure. For example, the structure Noun Phrase–Verb–Noun Phrase corresponds to indefinitely many clauses: The dog chewed its bone, The cat scratched the dog, Dogs like meat and so on. The process of insertion is not simple. As mentioned above, particular lexical items only fit into particular pieces of structure – some verbs combine with one noun phrase, others with two, and a third set of verbs with three. Some singular nouns combine with the and a, and some exclude them. In addition there are many instances both of particular lexical items that typically combine with other specific lexical items (rock hard ) and of fixed phrases (know something like the back of one’s hand ). Current searches of very large electronic bodies of text are beginning to reveal just how pervasive these restricted combinations and fixed phrases are.

Information about the interplay between lexical items and syntactic structure has always been available in all but the smallest dictionaries.

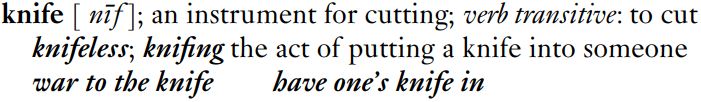

Chambers 20th Century Dictionary(1983), for example, includes the following information in the entry for knife.

The entry gives some information about syntax; the verb is described as transitive, which means that in the basic ACTIVE DECLARATIVE construction it requires a noun phrase to its right. There is a rough guide to the pronunciation which does not use the International Phonetic Alphabet, a definition of the meaning of the noun, two words that are derived from the basic stem and two idiomatic phrases. The entry would not be very useful for a non-native speaker with a limited knowledge of English, but the dictionary is intended primarily for native speakers. The limitations become clear from the entry for put, which describes it as a transitive verb but does not say that put is different from knife in requiring a noun phrase and prepositional phrase to its right – put the parcel on the table vs *put the parcel. The entry for accuse does not specify that it requires a noun phrase and a prepositional phrase to its right, nor that the preposition must be of – Mandragora accused Panjandrum of plagiarism.

This kind of information is supplied in dictionaries intended for schoolchildren and for people learning English as a second language, and must be included in adequate descriptions of English. What counts as an adequate description of a language? The major grammars of languages, particularly languages that are both spoken and written, include information about all the word, phrase, clause and sentence constructions in a large body of data, mostly drawn from written texts but nowadays likely to include transcripts of speech. The current most comprehensive grammar of English, A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language by Sir Randolph Quirk et al. (1985), also includes information about how sentences combine to form larger texts and about typical or fixed combinations of lexical items.

Another approach to the writing of grammars has as its goal the writing of explicit rules, which ‘generate’ sentences. This task involves the writing of rules that specify syntactic constructions, it involves the writing of an accurate and detailed dictionary and it involves a detailed account of how the correct lexical item is inserted into a given syntactic structure and of how only acceptable combinations of lexical items are specified. This approach must also ensure that the rules do not specify unacceptable structures. This introduction does not aim at completely explicit rules, but we will exploit the idea of explicit rules and of a system of rules in order to organize our discussion of the lexicon. What is of crucial concern, of course, is the set of concepts to be used in the analysis of syntax (whether the syntax of English or of some other language); that is what we will focus on.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة