Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Vowel classification

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

74-6

18-3-2022

1820

Vowel classification

The labels outlined in the previous section are helpful, but may leave questions unresolved when used in comparisons between different languages or different accents of the same language. Thus, French [u:] in rouge is very close in quality to English [u:] in goose, but not identical; the French vowel is a little more peripheral, slightly higher and more back. Similarly, [o:] in rose for a GA speaker is slightly lower and more centralized than ‘the same’ vowel for a speaker of Scottish English. None of the descriptors introduced so far would allow us to make these distinctions clear, since in the systems of the languages or accents concerned, these pairs of vowels would quite appropriately be described as long, high, back and rounded, or long, high-mid, back and rounded respectively.

Furthermore, a classification of this sort, based essentially on articulation, is arguably less appropriate for vowels than for consonants. In uttering a vowel, the important thing is to produce a particular sort of auditory impression, so that someone listening understands which vowel in the system you are aiming at; but it does not especially matter which articulatory strategies you use to convey that auditory impression. If you were asked to produce an [u:], but not allowed to round your lips, then with a certain amount of practice you could make at least something very similar; and yet it would not be a rounded vowel in the articulatory sense, although you would have modified the shape of your vocal tract to make it sound like one. This is not possible with most consonants, where the auditory impression depends on the particular articulators used, and how close they get, not just the overall shape of the vocal tract and the effect that has on a passing airstream. It is true that the whole oral tract is a continuum, but it is easier to see the places for consonants as definite ‘stopping off places’ along that continuum, helped by the fact that most consonants are obstruents, and we can feel what articulators are involved.

One possible solution is to abandon an articulatory approach to vowel classification altogether, and turn instead to an analysis of the speech wave itself. it is true that most speakers of particular accents or even languages will produce certain vowels in an articulatorily similar fashion. For comparative purposes, what we need is an approach which allows vowel qualities to be expressed as relative rather than absolute values.

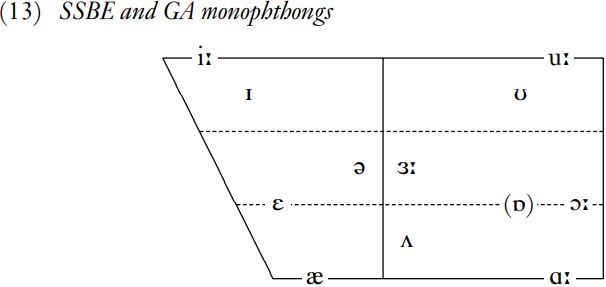

We can achieve this comparative perspective by plotting vowels on a diagram rather than simply defining them in isolation. The diagram conventionally used for this purpose is known as the Vowel Quadrilateral, and is an idealized representation of the vowel space, roughly between palatal and velar, where vowels can be produced in the vocal tract. The left edge corresponds to the palatal area, and hence to front vowels, and the right edge to the velar area, and back vowels. The top line extends slightly further than the bottom one because there is physically more space along the roof of the mouth than along the base. Finally, the chart is conventionally divided into six sectors, allowing high, high-mid, low-mid and low vowels to be plotted, as well as front, central and back ones. There is no way of reading information on rounding directly from the vowel quadrilateral, so that vowels are typically plotted using an IPA symbol rather than a dot; it is essential to learn these IPA symbols to see which refer to rounded, and which to unrounded vowels. The SSBE and GA monophthongs discussed in Section 6.2 are plotted in (13); the monophthongs of the two accents are similar enough to include on a single chart, although the [ɒ] vowel is bracketed, since it occurs in SSBE but not in GA, where words like lot have low [ɑ:] instead.

Diphthongs are not really well suited to description in terms of the labels introduced above, since they are essentially trajectories of articulation starting at one point and moving to another; in this respect, they are parallel to affricate consonants. Saying that [ɔI] in noise, for instance,

is a low-mid back rounded vowel followed by a high front unrounded vowel would not distinguish it from a sequence of vowels in different syllables or even different words; but the diphthong in noise is clearly different from the sequence of independent vowels in law is. Using the vowel quadrilateral, we can plot the changes in pronunciation involved in the production of a diphthong using arrows, as in (14). Plotting several diphthongs in this way can lead to a very messy chart, but it is nonetheless helpful in clarifying exactly how a particular diphthong is composed, and what its starting and stopping points are; and the notation reminds us that a symbolic representation like [ɔI] is actually short-hand for a gradual articulatory and auditory movement.

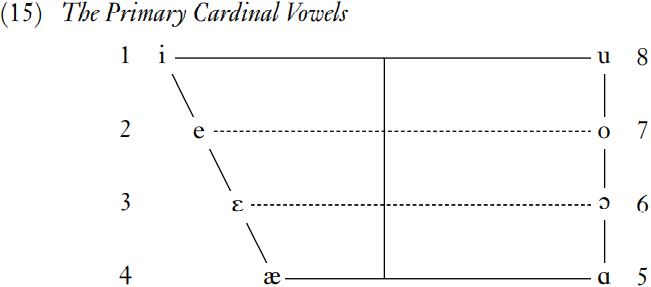

However, plotting vowels on the quadrilateral is only reliable if the person doing the plotting is quite confident about the quality she is hearing, and this can be difficult to judge without a good deal of experience, especially if a non-native accent or language is being described. To provide a universal frame of reference for such situations, phoneticians often work with an idealized set of vowels known as the Cardinal Vowels. For our purposes, we need introduce only the primary cardinals, which are conventionally numbered 1–8. Cardinal Vowel 1 is produced by raising and fronting the tongue as much as possible; any further, and a palatal fricative would result.

This vowel is like a very extreme form of English [i:] in fleece. Its opposite, in a sense, is Cardinal Vowel 5, the lowest, backest vowel that can be produced without turning into a fricative; this is like a lower, backer version of SSBE [ɑ:] in palm. Between these two fixed points, organized equidistantly around the very edges of the vowel quadrilateral, are the other six primary cardinal vowels, as shown in (15). Cardinal 8 is like English [u:] in goose, but again higher and backer; similarly, Cardinals 3, 4 and 6 can be compared with the vowels of English dress, trap and thought, albeit more extreme in articulation. Finally, Cardinals 2 and 7 are, like the monophthongal pronunciations of a Scottish English speaker in words like day, go. The steps between Cardinals 1–4 and 5–8 should be articulatorily and acoustically equidistant, and lip rounding also increases from Cardinals 6, through 7, to 8.

In truth, the only way of learning the Cardinal Vowels properly, and ensuring that they can act as a fixed set of reference points as they were designed to do, is to learn them from someone who already knows the system, and do a considerable amount of practice (various tapes and videos are available if you wish to do this). For the moment, what matters is to have an idea of what the Cardinal Vowels are, and what the theoretical justification for such a system is, in terms of describing the vowels of an unfamiliar language, or giving a principled account of the differences between the vowels of English and some other language, or different accents of English. We turn to such differences, as well as a more detailed outline of English vowel phonemes and allophones .

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)