Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-20

Date: 2024-05-29

Date: 2024-03-11

|

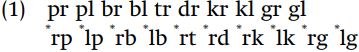

Previous chapters have focused on rules, but we haven’t paid much attention to how they should be formulated. English has rules defining allowed clusters of two consonants at the beginning of the word. The first set of consonant sequences in (1) is allowed, whereas the second set of sequences is disallowed.

This restriction is very natural and exists in many languages – but it is not inevitable, and does not reflect any insurmountable problems of physiology or perception. Russian allows many of these clusters, for example [rtutj ] ‘mercury’ exemplifies the sequence [rt] which is impossible in English.

We could list the allowed and disallowed sequences of phonemes and leave it at that, but this does not explain why these particular sequences are allowed. Why don’t we find a language which is like English, except that the specific sequence [lb] is allowed and the sequence [bl] is disallowed? An interesting generalization regarding sequencing has emerged after comparing such rules across languages. Some languages (e.g. Hawaiian) do not allow any clusters of consonants and some (Bella Coola, a Salishan language of British Columbia) allow any combination of two consonants, but no language allows initial [lb] without also allowing [bl]. This is a more interesting and suggestive observation, since it indicates that there is something about such sequences that is not accidental in English; but it is still just a random fact from a list of accumulated facts if we have no basis for characterizing classes of sounds, and view the restrictions as restrictions on letters, as sounds with no structure.

There is a rule in English which requires that all vowels be nasalized when they appear before a nasal consonant, and thus we have a rule something like (2).

If rules just replace one arbitrary list of sounds by another list when they stand in front of a third arbitrary list, we have to ask why these particular sets of symbols operate together. Could we replace the symbol [n] with the symbol [tʃ ], or the symbol [õ] with the symbol [ø], and still have a rule in some language? It is not likely to be an accident that these particular symbols are found in the rule: a rule similar to this can be found in quite a number of languages, and we would not expect this particular collection of letters to assemble themselves into a rule in many languages, if these were just random collections of letters.

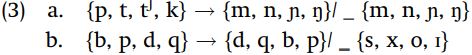

Were phonological rules stated in terms of randomly assembled symbols, there would be no reason to expect (3a) to have a different status from (3b).

Rule (3a) – nasalization of stops before nasals – is quite common, but (3b) is never found in human language. This is not an accident, but rather reflects the fact that the latter process cannot be characterized in terms of a unified phonetic operation applying to a phonetically defined context. The insight which we have implicitly assumed, and make explicit here, is that rules operate not in terms of specific symbols, but in terms of definable classes. The basis for defining those classes is a set of phonetic properties.

As a final illustration of this point, rule (4a) is common in the world’s languages but (4b) is completely unattested.

The first rule refers to phonetically definable classes of segments (velar stops, alveopalatal affricates, front vowels), and the nature of the change is definable in terms of a phonetic difference (velars change place of articulation and become alveopalatals). The second rule cannot be characterized by phonetic properties: the sets {p, r}, {i, b}, and {o, n} are not defined by some phonetic property, and the change of [p] to [i] and [r] to [b] has no coherent phonetic characterization.

The lack of rules like (4b) is not just an isolated limitation of knowledge – it’s not simply that we haven’t found the specific rules (4b) but we have found (4a) – but rather these kinds of rules represent large, systematic classes. (3b) and (4b) represent a general kind of rule, where classes of segments are defined arbitrarily. Consider the constraint on clusters of two consonants in English. In terms of phonetic classes, this reduces to the simple rule that the first consonant must be a stop and the second consonant must be a liquid. The second rule changes vowels into nasalized vowels before nasal consonants. The basis for defining these classes will be considered now

|

|

|

|

دراسة تحدد أفضل 4 وجبات صحية.. وأخطرها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|