Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Phrases

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

66-3

5-8-2022

2789

Phrases

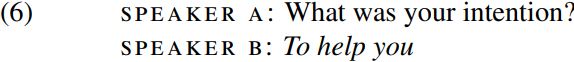

To put our discussion on a concrete footing, let’s consider how an elementary two-word phrase such as that produced by speaker B in the following mini-dialogue is formed:

As speaker B’s utterance illustrates, the simplest way of forming a phrase is by merging (a technical term meaning ‘combining’) two words together: for example, by merging the word help with the word you in (1), we form the phrase help you. The resulting phrase help you seems to have verb-like rather than noun-like properties, as we see from the fact that it can occupy much the same range of positions as the simple verb help, and hence e.g. occur after the infinitive particle to:

By contrast, the phrase help you cannot occupy the kind of position occupied by a pronoun such as you, as we see from (3) below:

So, it seems clear that the grammatical properties of a phrase like help you are determined by the verb help, and not by the pronoun you. Much the same can be said about the semantic properties of the expression, since the phrase help you describes an act of help, not a kind of person. Using the appropriate technical terminology, we can say that the verb help is the head of the phrase help you, and hence that help you is a verb phrase: and in the same way as we abbreviate category labels like verb to V, so too we can abbreviate the category label verb phrase to VP. If we use the traditional labelled bracketing technique to represent the category of the overall verb phrase help you and of its constituent words (the verb help and the pronoun you), we can represent the structure of the resulting phrase as in (4) below:

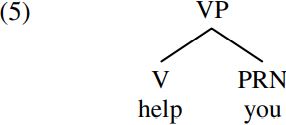

An alternative (equivalent) way of representing the structure of phrases like help you is via a labelled tree diagram such as (5) below (which is a bit like a family tree diagram – albeit for a small family):

What the tree diagram in (5) tells us is that the overall phrase help you is a verb phrase (VP), and that its two constituents are the verb (V) help and the pronoun (PRN) you. The verb help is the head of the overall phrase (and so is the key word which determines the grammatical and semantic properties of the phrase help you); introducing another technical term at this point, we can say that conversely, the VP help you is a projection of the verb help – i.e. it is a larger expression formed by merging the head verb help with another constituent of an appropriate kind. In this case, the constituent which is merged with the verb help is the pronoun you, which has the grammatical function of being the complement (or direct object) of the verb help. The head of a projection/phrase determines the grammatical properties of its complement: in this case, since help is a transitive verb, it requires a complement with accusative case (e.g. a pronoun like me/us/him/them), and this requirement is satisfied here since you can function as an accusative form.

The tree diagram in (5) is entirely equivalent to the labelled bracketing in (4), in the sense that the two provide us with precisely the same information about the structure of the phrase help you. The differences between a labelled bracketing like (4) and a tree diagram like (5) are purely notational: each category is represented by a single labelled node in a tree diagram (i.e. by a point in the tree which carries a category label like VP, V or PRN), but by a pair of labelled brackets in a labelled bracketing. In each case, category labels like V/verb and PRN/pronoun should be thought of as shorthand abbreviations for the set of grammatical features which characterize the overall grammatical properties of the relevant words (e.g. the pronoun you as used in (5) carries a set of features including [second-person] and [accusative-case], though these features are not shown by the category label PRN).

Since our goal in developing a theory of Universal Grammar is to uncover general structural principles governing the formation of phrases and sentences, let’s generalize our discussion of (5) at this point and hypothesize that all phrases are formed in essentially the same way as the phrase in (5), namely by a binary (i.e. pairwise) merger operation which combines two constituents together to form a larger constituent. In the case of (5), the resulting phrase help you is formed by merging two words. However, not all phrases contain only two words – as we see if we look at the structure of the phrase produced by speaker B in (6) below:

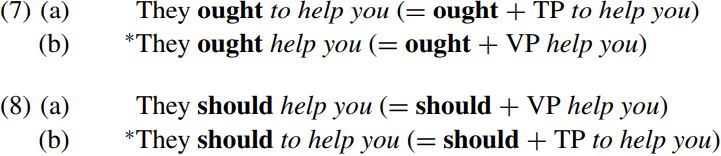

The phrase in (6B) is formed by merging the infinitive particle to with the verb phrase help you. What’s the head of the resulting phrase to help you? A reasonable guess would be that the head is the infinitival tense particle/T to, so that the resulting expression to help you is an infinitival TP (= infinitival tense projection = infinitival tense phrase). This being so, we’d expect to find that TPs containing infinitival to have a different distribution (and so occur in a different range of positions) from VPs/verb phrases – and this is indeed the case, as we see from the contrast below:

If we assume that help you is a VP whereas to help you is a TP, we can account for the contrasts in (7) and (8) by saying that ought is the kind of word which selects (i.e. ‘takes’) an infinitival TP as its complement, whereas should is the kind of word which selects an infinitival VP as its complement. Implicit in this claim is the assumption that different words like ought and should have different selectional properties which determine the range of complements they permit (as we saw in §2.11).

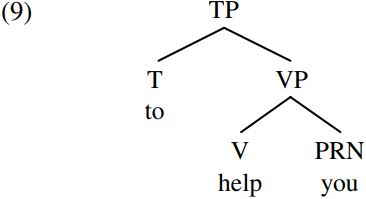

The infinitive phrase to help you is formed by merging the infinitive particle to with the verb phrase help you. If infinitival to is a non-finite tense particle (belonging to the category T) and if to is the head of the phrase to help you, the structure formed by merging the infinitival T-particle to with the verb phrase/VP help you in (5) will be the TP (i.e. non-finite/infinitival tense projection/phrase) in (9) below:

The head of the resulting infinitival tense projection to help you is the infinitive particle to, and the verb phrase help you is the complement of to; conversely, to help you is a projection of to. In keeping with our earlier observation that ‘The head of a projection/phrase determines grammatical properties of its complement’, the non-finite tense particle to requires an infinitival complement: more specifically, to requires the head V of its VP complement to be a verb in its infinitive form, so that we require the infinitive form help after infinitival to (and not a form like helping/helped/helps). Refining our earlier observation somewhat, we can therefore say that ‘The head of a projection/phrase determines grammatical properties of the head word of its complement’. In (9), to is the head of the TP to help you, and the complement of to is the VP help you; the head of this VP is the V help, so that to determines the form of the V help (requiring it to be in the infinitive form help).

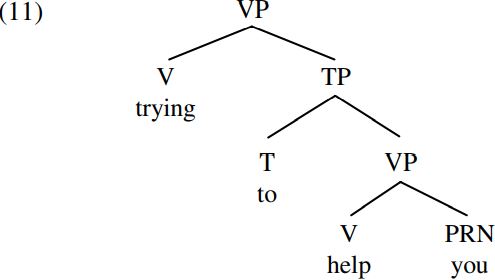

More generally, our discussion here suggests that we can build up phrases by a series of binary merger operations which combine successive pairs of constituents to form ever larger structures. For example, by merging the infinitive phrase to help you with the verb trying, we can form the even larger phrase trying to help you produced by speaker B in (10) below:

The resulting phrase trying to help you is headed by the verb trying, as we see from the fact that it can be used after words like be, start or keep which select a complement headed by a verb in the -ing form (cf. They were/started/kept trying to help you). This being so, the italicized phrase produced by speaker B in (10) is a VP (= verb phrase) which has the structure (11) below:

(11) tells us (amongst other things) that the overall expression trying to help you is a verb phrase/VP; its head is the verb/V trying, and the complement of trying is the TP/infinitival tense phrase to help you: conversely, the VP trying to help you is a projection of the V trying. An interesting property of syntactic structures illustrated in (11) is that of recursion – that is, the property of allowing a given structure to contain more than one instance of a given category (in this case, more than one verb phrase/VP – one headed by the verb help and the other headed by the verb trying).

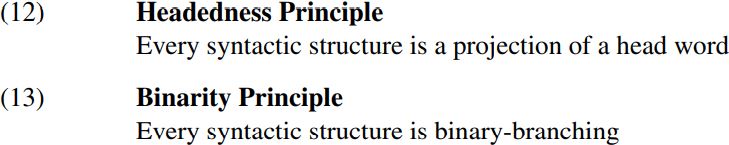

Since our goal in developing a theory of Universal Grammar/UG is to attempt to establish universal principles governing the nature of linguistic structure, an important question to ask is whether there are any general principles of constituent structure which we can abstract from structures like (5), (9) and (11). If we look closely at the relevant structures, we can see that they obey the following two (putatively universal) constituent structure principles:

(The term syntactic structure is used here as an informal way of denoting an expression which contains two or more constituents.) For example, the structure (11) obeys the Headedness Principle (12) in that the VP help you is headed by the V help, the TP to help you is headed by the T to, and the VP trying to help you is headed by the V trying. Likewise, (11) obeys the Binarity Principle (13) in that the VP help you branches into two immediate constituents (in the sense that it has two constituents immediately beneath it, namely the V help and the PRN you), the TP to help you branches into two immediate constituents (the non-finite tense particle T to and the VP help you), and the VP trying to help you likewise branches into two immediate constituents (the V trying and the TP to help you). Our discussion thus leads us towards a principled account of constituent structure – i.e. one based on a set of principles of Universal Grammar.

There are several reasons for trying to uncover constituent structure principles like (12) and (13). From a learnability perspective, such principles reduce the range of alternatives which children have to choose between when trying to determine the structure of a given kind of expression: they therefore help us develop a more constrained theory of syntax. Moreover, additional support for the Binarity Principle comes from evidence that phonological structure is also binary, in that (e.g.) a syllable like bat has a binary structure, consisting of the onset |b| and the rhyme |at|, and the rhyme in turn has a binary structure, consisting of the nucleus |a| and the coda|t| (see Radford et al. 1999, pp. 88ff. for an outline of syllable structure). Likewise, there is evidence that morphological structure is also binary: for example (under the analysis proposed in Radford et al. 1999, p. 164), the noun indecipherability is formed by adding the prefix de- to the noun cipher to form the verb decipher; then adding the suffix -able to this verb to form the adjective decipherable; then adding the prefix in- to this adjective to form the adjective indecipherable; and then adding the suffix -ity to the resulting adjective to form the noun indecipherability. It would therefore seem that binarity is an inherent characteristic of the phonological, morphological and syntactic structure of natural languages. There is also a considerable body of empirical evidence in support of a binary-branching analysis of a range of syntactic structures in a range of languages (see e.g. Kayne 1984a) – though much of this work is highly technical and it would therefore not be appropriate to consider it here.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)