Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Testing structure

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

84-3

6-8-2022

2582

Testing structure

Thus far, we have argued that phrases and sentences are built up by merging successive pairs of constituents into larger and larger structures, and that the resulting structure can be represented in terms of a labelled tree diagram. The tree diagrams which we use to represent syntactic structure make specific claims about how sentences are built up out of various different kinds of constituent (i.e. syntactic unit): hence, trees can be said to represent the constituent structure of sentences. But this raises the question of how we know (and how we can test) whether the claims made about syntactic structure in tree diagrams are true. So far, we have relied mainly on intuition in analyzing the structure of sentences – we have in effect guessed at the structure. However, it is unwise to rely on intuition in attempting to determine the structure of a given expression in a given language. For, while experienced linguists over a period of years tend to acquire fairly strong intuitions about structure, novices by contrast tend to have relatively weak, uncertain and unreliable intuitions; moreover, even the intuitions of supposed experts may ultimately turn out to be based on little more than personal preference.

For this reason, it is more satisfactory (and more accurate) to regard constituent structure as having the status of a theoretical construct. That is to say, it is part of the theoretical apparatus which linguists find they need to make use of in order to explain certain data about language (just as molecules, atoms and subatomic particles are constructs which physicists find they need to make use of in order to explain the nature of matter in the universe). It is no more reasonable to rely wholly on intuition to determine syntactic structure than it would be to rely on intuition to determine molecular structure. Inevitably, then, much of the evidence for syntactic structure is of an essentially empirical character, based on the observed grammatical properties of particular types of expression. The evidence typically takes the form ‘Unless we posit that such-and-such an expression has such-and-such a constituent structure, we shall be unable to provide a principled account of the observed grammatical properties of the expression.’ Thus, structural representations ultimately have to be justified in empirical terms, i.e. in terms of whether or not they provide a principled account of the grammatical properties of phrases and sentences.

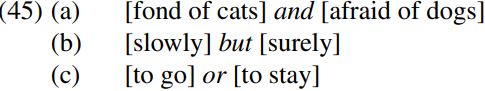

So, a tree diagram like (44) has the status of a hypothesis (i.e. untested and unproven assumption) about the structure of the corresponding sentence The chairman has resigned from the board. How can we test our hypothesis and determine whether (44) is or isn’t an appropriate representation of the structure of the sentence? The answer is that there are a number of standard heuristics (i.e. ‘tests’) which we can use to determine structure. One such test relates to the phenomenon of coordination. English and other languages have a variety of coordinating conjunctions (which we might designate by the category label CONJ – or perhaps just J) like and/but/or which can be used to coordinate (= conjoin = join together) expressions such as those bracketed below:

In each of the expressions in (45), an italicized coordinating conjunction has been used to conjoin the bracketed pairs of expressions. Clearly, any adequate grammar of English will have to provide a principled answer to the question: ‘What kinds of strings (i.e. sequences of words) can and cannot be coordinated?’

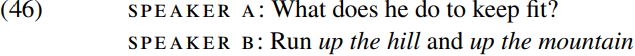

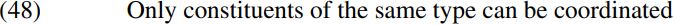

Now, it turns out that we can’t just coordinate any random set of strings, as we see by comparing the grammatical reply produced by speaker B in (46) below:

with the ungrammatical reply produced by speaker B in (47) below:

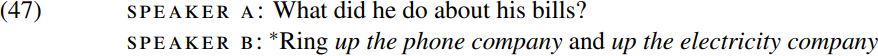

Why should it be possible to coordinate the string up the hill with the string up the mountain in (46), but not possible to coordinate the string up the phone company with the string up the electricity company in (47)? We can provide a principled answer to this question in terms of constituent structure: the italicized string up the hill in (46) is a constituent of the phrase run up the hill (up the hill is a prepositional phrase, in fact), and so can be coordinated with another similar type of prepositional phrase (e.g. a PP such as up the mountain, or down the hill, or along the path, etc.). Conversely, however, the string up the phone company in (47) is not a constituent of the phrase ring up the phone company, and so cannot be coordinated with another similar string like up the electricity company. (Traditional grammarians say that up is associated with ring in expressions like ring up someone, and that the expression ring up forms a kind of complex verb which carries the sense of ‘telephone’.) On the basis of contrasts such as these, we can formulate the following generalization:

Why should it be possible to coordinate the string up the hill with the string up the mountain in (46), but not possible to coordinate the string up the phone company with the string up the electricity company in (47)? We can provide a principled answer to this question in terms of constituent structure: the italicized string up the hill in (46) is a constituent of the phrase run up the hill (up the hill is a prepositional phrase, in fact), and so can be coordinated with another similar type of prepositional phrase (e.g. a PP such as up the mountain, or down the hill, or along the path, etc.). Conversely, however, the string up the phone company in (47) is not a constituent of the phrase ring up the phone company, and so cannot be coordinated with another similar string like up the electricity company. (Traditional grammarians say that up is associated with ring in expressions like ring up someone, and that the expression ring up forms a kind of complex verb which carries the sense of ‘telephone’.) On the basis of contrasts such as these, we can formulate the following generalization:

A constraint (i.e. principle imposing restrictions on certain types of grammatical operation) along the lines of (48) is assumed in much work in traditional grammar.

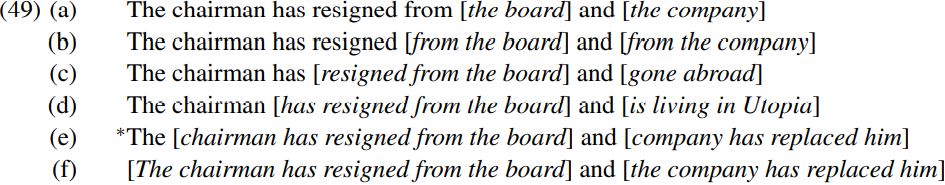

Having established the constraint (48), we can now make use of it as a way of testing the tree diagram in (44) above. In this connection, consider the data in (49) below (in which the bracketed strings have been coordinated by and):

(49a) provides us with evidence in support of the claim in (44) that the board is a determiner phrase constituent, since it can be coordinated with another DP like the company; similarly, (49b) provides us with evidence that from the board is a prepositional phrase constituent, since it can be coordinated with another PP like from the company; likewise, (49c) provides evidence that resigned from the board is a verb phrase constituent, since it can be coordinated with another VP like gone abroad; in much the same way, (49d) provides evidence that has resigned from the board is a T-bar constituent, since it can be coordinated with another

(49a) provides us with evidence in support of the claim in (44) that the board is a determiner phrase constituent, since it can be coordinated with another DP like the company; similarly, (49b) provides us with evidence that from the board is a prepositional phrase constituent, since it can be coordinated with another PP like from the company; likewise, (49c) provides evidence that resigned from the board is a verb phrase constituent, since it can be coordinated with another VP like gone abroad; in much the same way, (49d) provides evidence that has resigned from the board is a T-bar constituent, since it can be coordinated with another  like is living in Utopia (thereby providing interesting empirical evidence in support of the binary-branching structure assumed in the TP analysis of clauses, and against the ternary-branching analysis assumed in the S analysis of clauses); and in addition, (49f) provides evidence that the chairman has resigned from the board is a TP constituent, since it can be coordinated with another TP like the company has replaced him. Conversely, however, the fact that (49e) is ungrammatical suggests that (precisely as (44) claims) the string chairman has resigned from the board is not a constituent, since it cannot be coordinated with a parallel string like company has replaced him (and the constraint in (48) tells us that two strings of words can only be coordinated if both are constituents – and more precisely, if both are constituents of the same type). Overall, then, the coordination data in (49) provide empirical evidence in support of the analysis in (44). (It should be noted, however, that the coordination test is not always straightforward to apply, in part because there is more than one type of coordination – see e.g. Radford 1997a, pp. 104–7. Apparent complications arise in relation to sentences like ‘He is cross with her and in a pure mood’, where the AP/adjectival phrase cross with her has been coordinated with the PP/prepositional phrase in a pure mood: to say that these seemingly different AP and PP constituents are ‘of the same type’ requires a more abstract analysis than is implied by category labels like AP and PP, perhaps taking them to share in common the property of being predicative expressions. See Phillips 2003 for an alternative approach to coordination, and Johnson 2002 for problematic cases in German.)

like is living in Utopia (thereby providing interesting empirical evidence in support of the binary-branching structure assumed in the TP analysis of clauses, and against the ternary-branching analysis assumed in the S analysis of clauses); and in addition, (49f) provides evidence that the chairman has resigned from the board is a TP constituent, since it can be coordinated with another TP like the company has replaced him. Conversely, however, the fact that (49e) is ungrammatical suggests that (precisely as (44) claims) the string chairman has resigned from the board is not a constituent, since it cannot be coordinated with a parallel string like company has replaced him (and the constraint in (48) tells us that two strings of words can only be coordinated if both are constituents – and more precisely, if both are constituents of the same type). Overall, then, the coordination data in (49) provide empirical evidence in support of the analysis in (44). (It should be noted, however, that the coordination test is not always straightforward to apply, in part because there is more than one type of coordination – see e.g. Radford 1997a, pp. 104–7. Apparent complications arise in relation to sentences like ‘He is cross with her and in a pure mood’, where the AP/adjectival phrase cross with her has been coordinated with the PP/prepositional phrase in a pure mood: to say that these seemingly different AP and PP constituents are ‘of the same type’ requires a more abstract analysis than is implied by category labels like AP and PP, perhaps taking them to share in common the property of being predicative expressions. See Phillips 2003 for an alternative approach to coordination, and Johnson 2002 for problematic cases in German.)

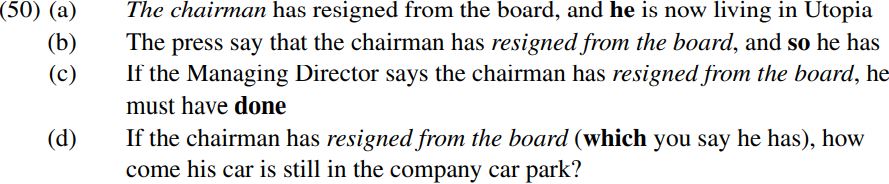

There are a variety of other ways of testing structure, but we will not attempt to cover them all here (see Radford 1997a, pp. 102–16 for more detailed discussion). However, we will briefly mention two which are already familiar from earlier discussion. We have noted that substitution is a useful tool for determining the categorial status of words. We can also use substitution as a way of testing whether a given string of words is a constituent or not, by seeing whether the relevant string can be replaced by (or serve as the antecedent of) a single word. In this connection, consider:

The fact that the expression the chairman in (50a) can be substituted (or referred back to) by a single word (in this case, the pronoun he) provides evidence in support of the claim in (44) that the chairman is a single constituent (a DP/determiner phrase, to be precise). Likewise, the fact that the expression resigned from the board in (50b,c,d) can serve as the antecedent of so/done/which provides evidence in support of the claim in (44) that resigned from the board is a constituent (more precisely, a VP/verb phrase).

The fact that the expression the chairman in (50a) can be substituted (or referred back to) by a single word (in this case, the pronoun he) provides evidence in support of the claim in (44) that the chairman is a single constituent (a DP/determiner phrase, to be precise). Likewise, the fact that the expression resigned from the board in (50b,c,d) can serve as the antecedent of so/done/which provides evidence in support of the claim in (44) that resigned from the board is a constituent (more precisely, a VP/verb phrase).

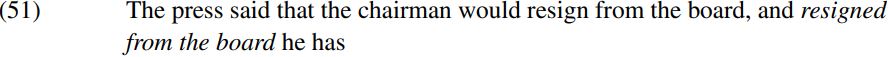

A further kind of constituent structure test which we made use above relates to the possibility of preposing a constituent in order to highlight it in some way (i.e. in order to mark it out as a topic containing familiar/old information, or a focused constituent containing unfamiliar/new information). In our earlier discussion of (32), (33) and (37) above, we concluded that only a maximal projection can be highlighted in this way. This being so, one way we can test whether a given expression is a maximal projection or not is by seeing whether it can be preposed. In this connection, consider the following sentence:

The fact that the italicized expression resigned from the board can be preposed in (51) indicates that it must be a maximal projection: this is consistent with the analysis in (44) which tells us that resigned from the board is a verb phrase which is the maximal projection of the verb resigned.

The fact that the italicized expression resigned from the board can be preposed in (51) indicates that it must be a maximal projection: this is consistent with the analysis in (44) which tells us that resigned from the board is a verb phrase which is the maximal projection of the verb resigned.

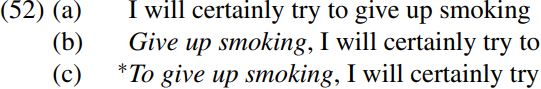

However, an important caveat which should be noted in relation to the preposing test is that particular expressions can sometimes be difficult (or even impossible) to prepose even though they are maximal projections. This is because there are constraints (i.e. restrictions) on such movement operations. One such constraint can be illustrated by the following contrast:

Here, the VP/verb phrase give up smoking can be highlighted by being preposed, but the TP/infinitival tense phrase to give up smoking cannot – even though it is a maximal projection (by virtue of being the largest expression headed by infinitival to). What is the nature of the restriction on preposing to+ infinitive expressions illustrated by the ungrammaticality of (52c)? The answer is not clear, but may be semantic in nature. When an expression is preposed, this is in order to highlight its semantic content in some way (e.g. for purposes of contrast – as in ‘Syntax, I don’t like but phonology I do’). It may be that its lack of intrinsic lexical content makes infinitival to an unsuitable candidate for highlighting, and this may in turn be reflected in the fact that infinitival to cannot carry contrastive stress – as we see from the ungrammaticality of ∗‘I don’t want to’, where capitals mark contrastive stress. What this suggests is that:

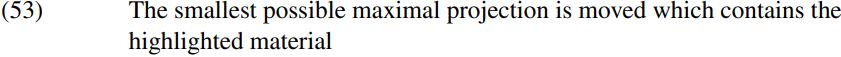

So, if we want to highlight the semantic content of the VP give up smoking, we prepose the VP give up smoking rather than the TP to give up smoking because the VP is smaller than the TP containing it.

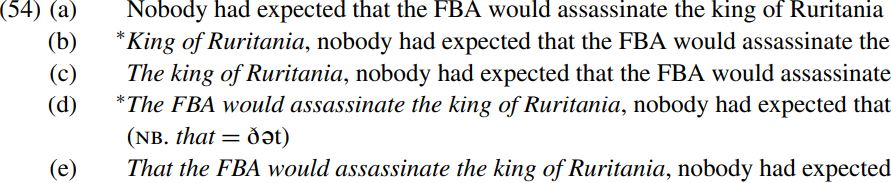

However, this is by no means the only constraint on preposing, as we see from (54) below (where FBA is an abbreviation for the Federal Bureau of Assassinations – a purely fictitious body, of course):

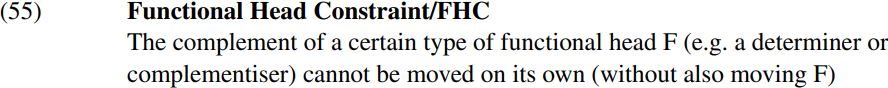

The ungrammaticality of (54b,d) tells us that we can’t prepose the NP king of Ruritania or the TP the FBA would assassinate the king of Ruritania. Why should this be? One possibility (briefly hinted at in Chomsky 1999) is that there may be a constraint on movement operations to the effect that a DP can be preposed but not an NP which is contained within a DP, and likewise that a CP can be preposed but not a TP which is contained within a CP. One implementation of this idea would be to posit a constraint like (55) below:

The ungrammaticality of (54b,d) tells us that we can’t prepose the NP king of Ruritania or the TP the FBA would assassinate the king of Ruritania. Why should this be? One possibility (briefly hinted at in Chomsky 1999) is that there may be a constraint on movement operations to the effect that a DP can be preposed but not an NP which is contained within a DP, and likewise that a CP can be preposed but not a TP which is contained within a CP. One implementation of this idea would be to posit a constraint like (55) below:

Suppose, then, that we want to highlight the NP king of Ruritania in (54) by preposing. (53) tells us to move the smallest possible maximal projection containing the highlighted material, and hence we first try to move this NP on its own: but the Functional Head Constraint tells us that it is not possible to prepose this NP on its own, because it is the complement of the determiner the. We therefore prepose the next smallest maximal projection containing the highlighted NP king of Ruritania – namely the DP the king of Ruritania; and as the grammaticality of (54c) shows, the resulting sentence is grammatical.

Suppose, then, that we want to highlight the NP king of Ruritania in (54) by preposing. (53) tells us to move the smallest possible maximal projection containing the highlighted material, and hence we first try to move this NP on its own: but the Functional Head Constraint tells us that it is not possible to prepose this NP on its own, because it is the complement of the determiner the. We therefore prepose the next smallest maximal projection containing the highlighted NP king of Ruritania – namely the DP the king of Ruritania; and as the grammaticality of (54c) shows, the resulting sentence is grammatical.

Now suppose that we want to highlight the TP the FBA would assassinate the king of Ruritania. (53) tells us to move the smallest maximal projection containing the highlighted material – but FHC (55) tells us that we cannot prepose a constituent which is the complement of a complementizer. Hence, we prepose the next smallest maximal projection containing the TP we want to highlight, namely the CP that the FBA would assassinate the king of Ruritania – as in (54e).

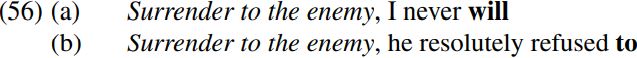

However, an apparent problem for the Functional Head Constraint (55) is posed by examples like:

The preposed verb phrase surrender to the enemy is the complement of will in (56a), and the complement of to in (56b). Given the analysis in §2.7 and §2.8, will is a finite T/tense constituent and to is a non-finite T/tense particle. If (as we have assumed so far) T is a functional category, we would expect the Functional Head Constraint (55) to block preposing of the VP surrender to the enemy because this VP is the complement of the functional T constituent will/to. The fact that the resulting sentences (56a,b) are grammatical might lead us to follow Chomsky (1999) in concluding that T is a substantive category rather than a functional category, and hence does not block preposing of its complement. Alternatively, it may be that the constraint only applies to certain types of functional category (as hinted at in (55)) – e.g. D and C but not T (perhaps because D and C are the ‘highest’ heads within nominal and clausal structures respectively – and indeed we shall reformulate this constraint along such lines).

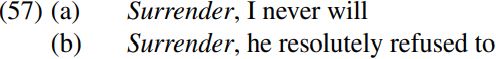

It is interesting to note that alongside sentences like (56) above in which a phrase has been highlighted by being preposed, we also find sentences like (57) below in which a single word has been preposed:

In (57) the verb surrender has been preposed on its own. At first sight, this might seem to contradict our earlier statement that only maximal projections can undergo preposing. However, more careful reflection shows that there is no contradiction here: after all, the maximal projection of a head H is the largest expression headed by H; and in a sentence like I never will surrender, the largest expression headed by the verb surrender is the verb surrender itself – hence, surrender in (57) is indeed a maximal projection. More generally, this tells us that an individual word can itself be a maximal projection, if it has no complement or specifier of its own.

The overall conclusion to be drawn from our discussion here is that the preposing test has to be used with care. If an expression can be preposed in order to highlight it, it is a maximal projection; if it cannot, this may either be because it is not a maximal projection, or because (even though it is a maximal projection) a syntactic constraint of some kind prevents it from being preposed, or because its head word has insufficient semantic content to make it a suitable candidate for highlighting.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)