Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2023-07-25

Date: 2023-09-23

Date: 2023-08-17

|

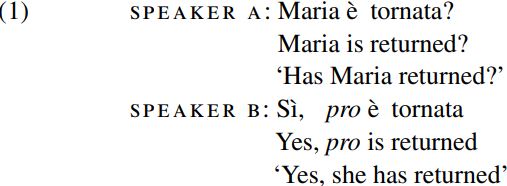

We are already familiar with one kind of null constituent from the discussion of the Null-Subject Parameter. There, we saw that alongside finite clauses like that produced by speaker A in the dialogue in (1) below with an overt subject like Maria, Italian also has finite clauses like that produced by speaker B, with a null subject pronoun conventionally designated as pro (and referred to affectionately as ‘little pro’):

One reason for positing that the sentence in (1B) has a null pro subject is that tornare ‘return’ (in the use illustrated here) is a one-place predicate which requires a subject: this requirement is satisfied by the overt subject Maria in (1A), and by the null pro subject in (1B). A second reason relates to the agreement morphology carried by the auxiliary e` ‘is’ and the participle tornata ‘returned’ in (1). Just as the form of the (third-person-singular) auxiliary e` ‘is’ and the (feminine-singular) participle tornata is determined via agreement with the overt (third-person-feminine singular) subject Maria in (1A), so too the auxiliary and participle agree in exactly the same way with the null pro subject in (1B), which (as used here) is third person feminine singular by virtue of referring to Maria. If the sentence in (1B) were subjectless, it is not obvious how we would account for the relevant agreement facts. Since all finite clauses in Italian allow a null pro subject, we can refer to pro as a null finite subject.

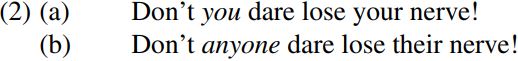

Although English is not an Italian-style null-subject language (in the sense that it is not a language which allows any and every kind of finite clause to have a null pro subject), it does have three different types of null subject (briefly discussed in exercise 1.1). One of these are imperative null subjects. As the examples in (2) below illustrate, an imperative sentence in English can have an overt subject which is either a second-person expression like you, or a third-person expression like anyone:

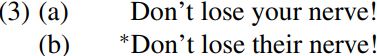

However, imperative null subjects are intrinsically second person, as the contrast in (3) below shows:

In other words, imperative null subjects seem to be a silent counterpart of you. One way of describing this is to say that the pronoun you can have a null spellout (and thereby have its phonetic features not spelled out – i.e. deleted/omitted) when it is the subject of an imperative sentence.

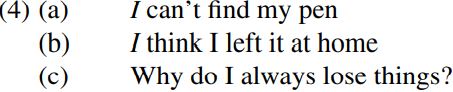

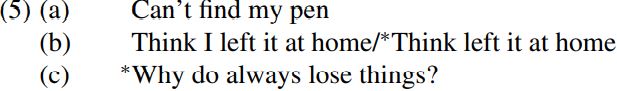

A second type of null subject found in English are truncated null subjects. In cryptic styles of colloquial spoken English (and also in diary styles of written English) a sentence can be truncated (i.e. shortened) by giving a subject pronoun like I/you/he/we/they a null spellout if it is the first word in a sentence. So, in sentences like those in (4) below:

the two italicized occurrences of the subject pronoun I can be given a null spellout because in each case I is the first word in the sentence, but not other occurrences of I – as we see from (5) below:

However, not all sentence-initial subjects can be truncated (e.g. we can’t truncate He in a sentence like He is tired, giving ∗Is tired): the precise nature of the constraints on truncation is unclear.

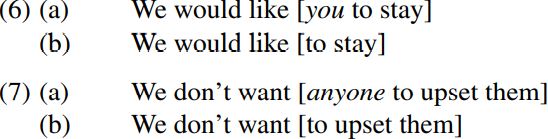

A third type of null subject found in English are non-finite null subjects, found in non-finite clauses which don’t have an overt subject. In this connection, compare the structure of the bracketed infinitive clauses in the (a) and (b) examples below:

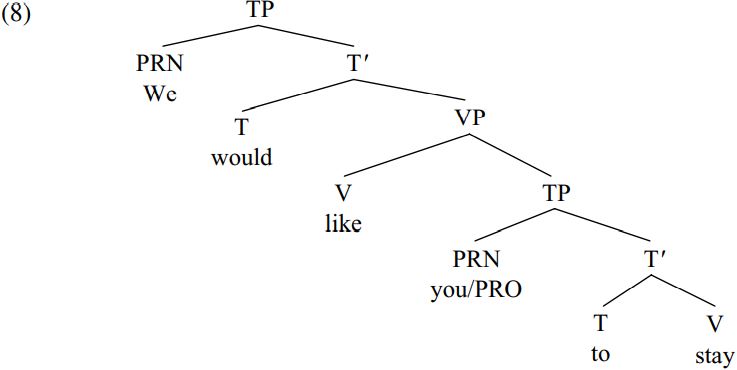

Each of the bracketed infinitive complement clauses in the (a) examples in (6) and (7) contains an overt (italicized) subject. By contrast, the bracketed complement clauses in the (b) examples appear to be subjectless. However, we shall argue that apparently subjectless infinitive clauses contain a null subject. The particular kind of null subject found in the bracketed clauses in the (b) examples has the same grammatical and referential properties as a pronoun, and hence appears to be a null pronoun. In order to differentiate it from the null (‘little pro’) subject found in finite clauses in null-subject languages like Italian, it is conventionally designated as PRO and referred to as ‘big PRO’. Given this assumption, a sentence such as (6b) will have a parallel structure to (6a), except that the bracketed TP has an overt pronoun you as its subject in (6a), but a null pronoun PRO as its subject in (6b) – as shown below:

Using the relevant technical terminology, we can say that the null PRO subject in (8) is controlled by (i.e. refers back to) the subject we of the matrix (= containing = next highest) clause – or, equivalently, that we is the controller or antecedent of PRO: hence, a structure like ‘We would like PRO to stay’ has an interpretation akin to that of ‘We would like ourselves to stay’. Verbs (such as like) which allow an infinitive complement with a PRO subject are said to function (in the relevant use) as control verbs; likewise, a complement clause with a null PRO subject is known as a control clause.

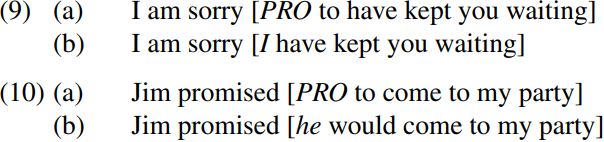

An obvious question to ask at this juncture is why we should posit that apparently subjectless infinitive complements like those bracketed in (6b) and (7b) above have a null PRO subject. Part of the motivation for PRO comes from considerations relating to argument structure. The verb stay (as used in (6b) above) is a one-place predicate which requires a subject argument – and positing a PRO subject for the stay clause satisfies the requirement for stay to have a subject. The null PRO subject of a control infinitive becomes overt if the infinitive clause is substituted by a finite clause, as we see from the paraphrases for the (a) examples given in the (b) examples below:

The fact that the bracketed clauses in the (b) examples contain an overt (italicized) subject makes it plausible to suppose that the bracketed clauses in the synonymous (a) examples have a null PRO subject. (Note, however, that only verbs which select both an infinitive complement and a finite complement allow a control clause to be substituted by a finite clause with an overt subject – hence, not a control verb like want in I want to go home because want does not allow a that-clause complement, as we see from the ungrammaticality of ∗I want that I should leave. Interestingly, Xu 2003 claims that all control verbs in Chinese allow an overt subject pronoun in place of PRO in control clauses.)

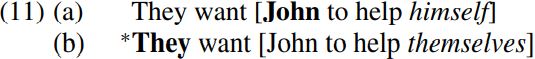

Further evidence in support of positing a null PRO subject in such clauses comes from the syntax of reflexive anaphors (i.e. self/selves forms such as myself/yourself/himself/themselves etc.). As examples such as the following indicate, reflexives generally require a local antecedent (the reflexive being italicized and its antecedent bold-printed):

In the case of structures like (11), a local antecedent means ‘an antecedent contained within the same [bracketed] clause/TP as the reflexive’. (11a) is grammatical because it satisfies this locality requirement: the antecedent of the reflexive himself is the noun John, and John is contained within the same (bracketed) help-clause as himself. By contrast, (11b) is ungrammatical because the reflexive themselves does not have a local antecedent (i.e. it does not have an antecedent within the bracketed clause containing it); its antecedent is the pronoun they, and they is contained within the want clause, not within the [bracketed] help clause. In the light of the requirement for reflexives to have a local antecedent, consider now how we account for the grammaticality of the following:

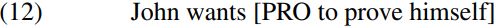

Given the requirement for reflexives to have a local antecedent, it follows that the reflexive himself must have an antecedent within its own [bracketed] clause. This requirement is satisfied in (12) if we assume that the bracketed complement clause has a PRO subject, and that PRO is the antecedent of himself. Since PRO in turn is controlled by John (i.e. John is the antecedent of PRO), this means that himself is coreferential to (i.e. refers to the same individual as) John.

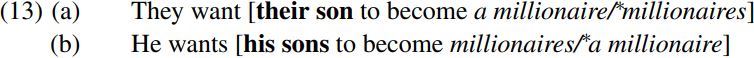

We can formulate a further argument in support of positing a PRO subject in apparently subjectless infinitive clauses in relation to the syntax of predicate nominals: these are nominal (i.e. noun-containing) expressions used as the complement of a copular (i.e. linking) verb such as be, become, remain (etc.) in expressions such as John was/became/remained my best friend, where the predicate nominal is my best friend, and the property of being/becoming/remaining my best friend is predicated of John. Predicate nominals of the relevant type have to agree in number with the subject of their own clause in copular constructions, as we see from examples such as the following:

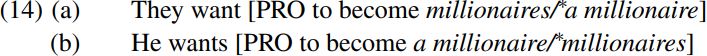

The italicized predicate nominal has to agree with the (bold-printed) subject of its own [bracketed] become clause, and cannot agree with the subject of the want clause. In the light of this local (clause-internal) agreement requirement, consider now how we account for the agreement pattern in (14) below:

If we posit that the become clause has a PRO subject which is controlled by (i.e. refers back to) the subject of the want clause, the relevant agreement facts can be accounted for straightforwardly: we simply posit that the predicate nominal (a) millionaire(s) agrees with PRO (since PRO is the subject of the become clause), and that PRO in (14a) is plural because its controller/antecedent is the plural pronoun they, and conversely that PRO in (14b) is singular because its antecedent/controller is the singular pronoun he.

A further argument in support of positing that control clauses have a silent PRO subject can be formulated in theoretical terms. We noted that finite auxiliaries have an [EPP] feature which requires them to have a subject specifier. Since finite auxiliaries belong to the category T of tense-marker, we can generalize this conclusion by positing that all finite T constituents have an [EPP] feature requiring them to have a subject. However, since we have argued that infinitival to also belongs to the category T (by virtue of its status as a non-finite tense-marker), we can suggest the broader generalization that not only a finite T but also a non-finite T containing the infinitive particle to has an [EPP] feature and hence must likewise project a subject. The analysis in (8) above is consistent with this generalization, since it posits that the stay clause either has an overt you subject or a null PRO subject, with either type of subject satisfying the [EPP] feature of to.

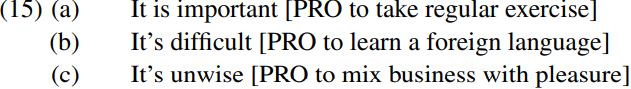

The overall conclusion which our discussion here leads us to is that just as infinitive complements like you to stay in (6a) have an overt subject (you), so too seemingly subjectless infinitive complements like to stay in (6b) have a null PRO subject – as shown in (8) above. In structures like (8), PRO has an explicit controller, which is the subject of the matrix clause (i.e. of the clause which immediately contains the control verb). However, this is not always the case, as we can see from structures like (15) below:

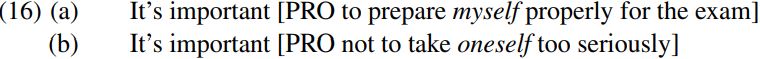

It is clear from examples like (16) below that apparently subjectless clauses like those bracketed in (15) and (16) must have a null PRO subject:

since the reflexives myself/oneself require a local antecedent within the bracketed clause containing them, and PRO serves the function of being the antecedent of the reflexive. However, PRO itself has no explicit antecedent in structures like (15) and (16). In such cases (where PRO lacks an explicit controller), PRO can either refer to some individual outside the sentence (e.g. the speaker in (16a)) or can have arbitrary reference (as in (16b)) and refer to ‘any arbitrary person you care to mention’ and hence have much the same interpretation as arbitrary one in sentences like ‘One can’t be too careful these days’. (See Landau 1999, 2001 for further discussion of control structures.)

|

|

|

|

دراسة: حفنة من الجوز يوميا تحميك من سرطان القولون

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تنشيط أول مفاعل ملح منصهر يستعمل الثوريوم في العالم.. سباق "الأرنب والسلحفاة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الطلبة المشاركون: مسابقة فنِّ الخطابة تمثل فرصة للتنافس الإبداعي وتنمية المهارات

|

|

|