Null C in finite clauses

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

124-4

الجزء والصفحة:

124-4

14/11/2022

14/11/2022

2358

2358

Null C in finite clauses

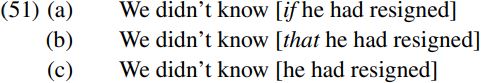

The overall conclusion to be drawn from our discussion is that all finite and infinitive clauses contain an overt or null T constituent which projects into TP (with the subject of the clause occupying the specifier position within TP). However, given that clauses can be introduced by complementizers such as if/that/for, a natural question to ask is whether apparently complementizer-less clauses can likewise be argued to be CPs headed by a null complementizer. In this connection, consider the following:

The bracketed complement clause is interpreted as interrogative in force in (51a) and declarative in force in (51b), and it is plausible to suppose that the force of the clause is determined by force features carried by the italicized complementizer introducing the clause: in other words, the bracketed clause is interrogative in force in (51a) because it is introduced by the interrogative complementizer if, and is declarative in force in (51b) because it is introduced by the declarative complementizer that.

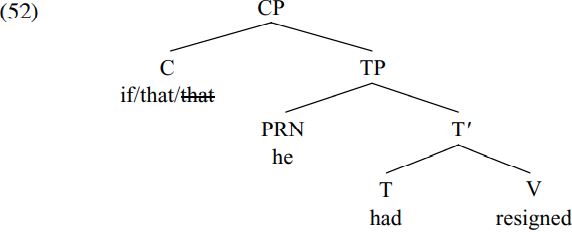

But now consider the bare (i.e. seemingly complementizerless) clause in (51c): this can only be interpreted as declarative in force (not as interrogative), so that (51c) is synonymous with (51b) and not with (51a). Why should this be? One answer is to suppose that the bracketed bare clause in (51c) is a CP headed by a null variant of the declarative complementizer that (below symbolized as  ), and that the bracketed complement clauses in (51a–c) have the structure (52) below:

), and that the bracketed complement clauses in (51a–c) have the structure (52) below:

Given the analysis in (52), we could then say that the force of each of the bracketed complement clauses in (51) is determined by the force features carried by the head C of the overall CP; in (51a) the clause is a CP headed by the interrogative complementizer if and so is interrogative in force; in (51b) it is a CP headed by the declarative complementizer that and so is declarative in force; and in (51c) it is a CP headed by a null variant of the declarative complementizer that and so is likewise declarative in force. More generally, the null complementizer analysis would enable us to arrive at a uniform characterization of all finite clauses as CPs in which the force of a clause is indicated by force features carried by an (overt or null) complementizer introducing the clause.

Empirical evidence in support of the null complementizer analysis of bare complement clauses like that bracketed in (51c) comes from coordination facts in relation to sentences such as:

In (53), the italicized bare clause has been coordinated with a bold-printed clause which is clearly a CP since it is introduced by the overt complementizer that. If we make the traditional assumption that only constituents of the same type can be coordinated, it follows that the italicized clause he had resigned in (53) must be a CP headed by a null counterpart of that because it has been coordinated with a bold-printed clause headed by the overt complementizer that – as shown in simplified form in (54) below:

In (53), the italicized bare clause has been coordinated with a bold-printed clause which is clearly a CP since it is introduced by the overt complementizer that. If we make the traditional assumption that only constituents of the same type can be coordinated, it follows that the italicized clause he had resigned in (53) must be a CP headed by a null counterpart of that because it has been coordinated with a bold-printed clause headed by the overt complementizer that – as shown in simplified form in (54) below:

What such an analysis implies is that the complementizer that can optionally be given a null phonetic spellout by having its phonetic features deleted in the PF component under certain circumstances: such an analysis dates back in spirit more than four decades (see e.g. Stockwell, Schachter and Partee 1973, p. 599).

What such an analysis implies is that the complementizer that can optionally be given a null phonetic spellout by having its phonetic features deleted in the PF component under certain circumstances: such an analysis dates back in spirit more than four decades (see e.g. Stockwell, Schachter and Partee 1973, p. 599).

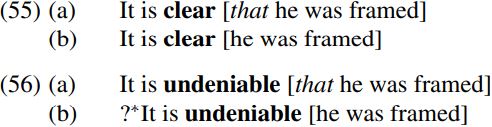

There are a number of conditions governing that-deletion. Lexical factors seem to play a part here, in that just as only some predicates which select an infinitival TP complement allow the infinitive particle to have a null spellout, so too only some predicates which select a that-clause complement allow that to have a null spellout. Hornstein (2000) suggests that passive participles and adjectives resist that-deletion, but the real situation seems rather more complex. For example, the adjective clear readily allows that-deletion, but the adjective undeniable does not:

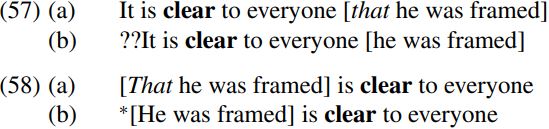

(Irrelevantly, (56b) is grammatical if taken to be two separate sentences – e.g. It is undeniable. He was framed.) There are also structural constraints on that-deletion. As Hawkins (2001, p. 13) notes, there is a strong adjacency effect insofar as that can generally only be deleted when it is asymmetrically c-commanded by and immediately adjacent to the relevant (bold-printed) predicate – as can be seen by comparing the examples in (55) above with those in (57) and (58) below:

In (57), the adjectival predicate clear asymmetrically c-commands but is not immediately adjacent to that (the two being separated by the intervening prepositional phrase to everyone), and so that cannot be given a null spellout. In (58), that is neither c-commanded by nor immediately adjacent to clear, so that once again that cannot be given a null spellout. The adjacency requirement might suggest that complementizer deletion involves cliticisation of the null complementizer onto the head immediately above it – but precisely how, when and why complementizers receive a null spellout remains shrouded in mystery.

So far, we have argued that seemingly complementizerless finite declarative complement clauses are introduced by a null C constituent (here analyzed as a null counterpart of the complementizer that). However, the null C analysis can be extended from finite embedded clauses to main (= root = principal = independent) clauses like those produced by speakers A and B in (59) below:

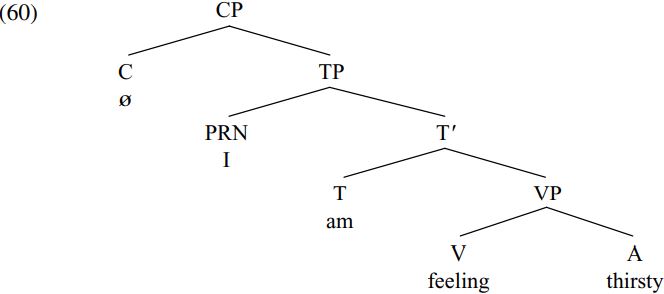

The sentence produced by speaker A is declarative in force (by virtue of being a statement). If force is marked by a force feature carried by the head C of CP, this suggests that such declarative main clauses are CPs headed by a null complementizer carrying a declarative force feature. However, it seems unlikely that the null complementizer introducing declarative main clauses is a null counterpart of that, since that in English is only used to introduce embedded clauses, not main clauses. Let’s therefore suppose that declarative main clauses in English are introduced by an inherently null complementizer (below symbolized as ø), and hence that the sentence produced by speaker A in (59) has the structure shown in (60) below:

Under the CP analysis of main clauses in (60), the declarative force of the overall sentence is attributed to the fact that the sentence is a CP headed by a null complementizer ø which carries a declarative force feature which we can represent as [Dec-Force]. (The purists among you may object that it’s not appropriate to call a null declarative particle introducing a main clause a complementizer when it doesn’t introduce a complement clause: however, in keeping with work over the past four decades, we’ll use the term complementizer/C in a more general sense here, to designate a category of word which can introduce both complement clauses and other clauses, and which serves to mark properties such as force and finiteness.)

From a cross-linguistic perspective, an analysis such as (60) which posits that main clauses are CPs headed by a force-marking complementizer is by no means implausible in that we find languages like Arabic in which both declarative and interrogative main clauses can be introduced by an overt complementizer, as the examples below illustrate (adapted from Ross 1970, p. 245):

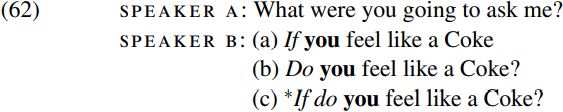

Moreover, there is some evidence from sentences like (62) below that inverted auxiliaries in main-clause yes–no questions occupy the head C position of CP in English:

The fact that the inverted auxiliary do in (62b) occupies the same pre-subject position (in front of the bold-printed subject you) as the complementizer if in (62a), and the fact that if and do are mutually exclusive (as we see from the fact that structures like (62c) are ungrammatical) suggests that inverted auxiliaries (like complementizers) occupy the head C position of CP. This in turn means that main-clause questions are CPs headed by a C which is interrogative in force by virtue of containing an interrogative force feature which can be represented as [Int-Force].

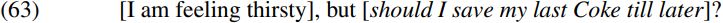

Interestingly, an interrogative main clause can be coordinated with a declarative main clause, as we see from sentences like (63) below:

In (63) we have two (bracketed) main clauses joined together by the coordinating conjunction but. The second (italicized) conjunct should I save my last Coke till later? is an interrogative CP containing an inverted auxiliary in the head C position of CP. Given the traditional assumption that only constituents which belong to the same category can be coordinated, it follows that the first conjunct I am feeling thirsty must also be a CP; and since it contains no overt complementizer, it must be headed by a null complementizer – precisely as assumed in (60) above.

The more general conclusion which our discussion leads us to is that all finite clauses have the status of CP constituents which are introduced by a complementizer. Finite complement clauses are CPs headed either by an overt complementizer like that or if or by a null complementizer (e.g. a null variant of that in the case of declarative complement clauses). Finite main clauses are likewise CPs headed by a C which contains an inverted auxiliary if the clause is interrogative, and an inherently null complementizer otherwise.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة