Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Null determiners

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

140-4

16/11/2022

2847

Null determiners

Thus far, we have argued that empty categories play an important role in the syntax of clauses in that clauses may contain a null subject, a null T constituent and a null C constituent. We now turn to argue that the same is true of the syntax of nominals(i.e. noun expressions), and that many bare nominals(i.e. noun expressions which contain no overt determiner or quantifier) are headed by a null determiner or null quantifier. The assumption that bare nominals contain a null determiner/quantifier has a long history – for example, Chomsky (1965, p. 108) suggests that the noun sincerity in a sentence such as Sincerity may frighten the boy is modified by a null determiner. Chomsky’s suggestion was taken up and extended in later work by Abney (1987), Longobardi (1994, 1996, 2001) and Bernstein (2001).

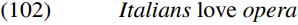

In this connection, consider the syntax of the italicized bare nominals in (102) below:

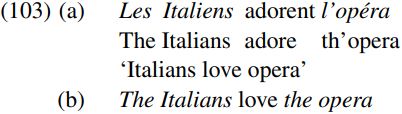

As we see from (103a) below, the French counterpart of the bare nominals in (102) are DPs headed by the determiner les/l’ (‘the’) – and indeed as (103b) shows, this type of structure is also possible in English:

This suggests that bare nominals like those italicized in (102) above are DPs headed by a null determiner, so that the overall sentence in (102) has the structure (104) below:

Given the analysis in (104), there would be an obvious parallelism between the syntax of clauses and nominals, in that just as canonical clauses are CPs headed by an overt or null C constituent, so too canonical nominals are DPs headed by an overt or null D constituent.

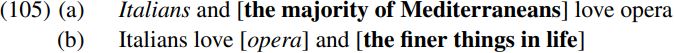

One piece of empirical evidence in support of analyzing bare nouns as DPs comes from sentences like:

The fact that the bare nouns Italians and opera can be coordinated with determiner phrases/DPs like the majority of Mediterraneans/the finer things in life (both headed by the determiner the) provides us with empirical evidence that bare nouns must be DPs, if only similar kinds of categories can be coordinated.

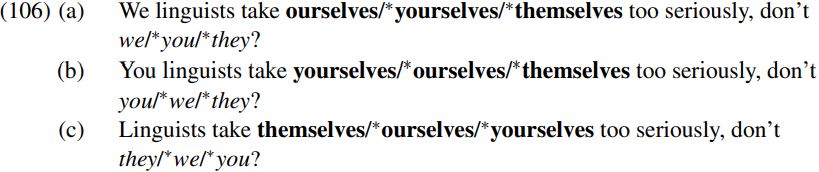

If (as we are suggesting here) there are indeed a class of null determiners, we should expect these to have specific grammatical, selectional and semantic properties of their own: and, as we shall see, there is indeed evidence that this is so. For one thing, the null determiner carries person properties – in particular, it is a third-person determiner. In this respect, consider sentences such as:

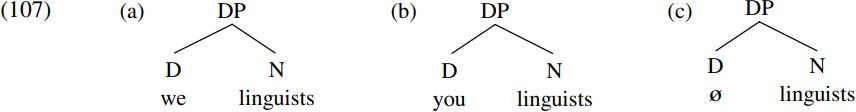

(106a) shows that a first-person expression such as we linguists can only bind (i.e. serve as the antecedent of) a first-person reflexive like ourselves, and can only be tagged by a first-person pronoun like we. (106b) shows that a second-person expression like you linguists can only bind a second-person reflexive like yourselves, and can only be tagged by a second-person pronoun like you. (106c) shows that a bare nominal like linguists can only bind a third-person reflexive like themselves and can only be tagged by a third-person pronoun like they. One way of accounting for the relevant facts is to suppose that the nominals we linguists/you linguists/linguists in (106a–c) are DPs with the respective structures shown in (107a–c):

and that the person properties of a DP are determined by the person features carried by its head determiner. If we is a first-person determiner, you is a second-person determiner and ø is a third-person determiner, the grammaticality judgments in (106a–c) above are precisely as the analysis in (107a–c) would lead us to expect.

and that the person properties of a DP are determined by the person features carried by its head determiner. If we is a first-person determiner, you is a second-person determiner and ø is a third-person determiner, the grammaticality judgments in (106a–c) above are precisely as the analysis in (107a–c) would lead us to expect.

In addition to having specific person properties, the null determiner ø also has specific selectional properties – as can be illustrated by the following set of examples:

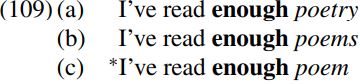

If each of the italicized bare nouns in (108) is the complement of a null (quantifying) determiner ø, the relevant examples show that ø can select as its complement an expression headed by a plural count noun like poems, or by a singular mass noun like poetry – but not by a singular count noun like poem. The complement selection properties of the null determiner ø mirror those of the overt quantifier enough:

The fact that ø has much the same selectional properties as a typical overt (quantifying) determiner such as enough strengthens the case for positing the existence of a null determiner ø, and for analyzing bare nominals as DPs headed by a null determiner (or QPs headed by a null quantifier).

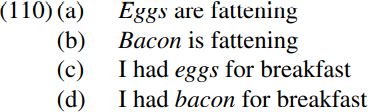

Moreover, there is evidence that the null determiner ø has specific semantic properties of its own – as we can illustrate in relation to the interpretation of the italicized nominals in the sentences below:

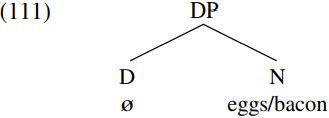

The nouns eggs and bacon in (110a/b) have a generic interpretation, paraphraseable as ‘eggs/bacon in general’. In (110c,d) eggs and bacon have a partitive interpretation, paraphraseable as ‘some eggs/bacon’. If we say that the italicized bare nominals are DPs/determiner phrases headed by a null determiner, as shown below:

we can say that the null determiner has the semantic property of being a generic or partitive quantifier, so that bare nominals are interpreted as generic or partitive expressions.

The claim that null determiners have specific semantic properties is an important one from a theoretical perspective in the light of the principle suggested by Chomsky (1995) that all constituents (or at any rate, all heads and maximal projections) must be interpretable at the semantics interface (i.e. must be able to be assigned a semantic interpretation by the semantic component of the grammar, and hence must contribute something to the meaning of the sentence containing them). This principle holds for null constituents as well as overt constituents, so that e.g. a seemingly null T constituent contains an abstract affix carrying an interpretable tense feature, and a null C constituent contains an abstract morpheme carrying an interpretable force feature. If the null D constituent found in structures like (110) and (111) is interpreted as a (generic or partitive) quantifier, the null D analysis will satisfy the relevant requirement.

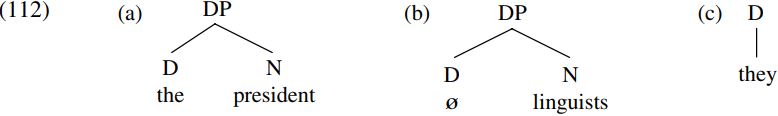

The assumption that bare nominals are headed by a null determiner allows us to arrive at a unitary characterization of the syntax of nominals. We can then say that nominals like the president which are modified by an overt determiner are DPs, bare nominals like Italians are DPs headed by a null determiner, and personal pronouns like they are determiners used without a complement – as shown below:

This means that all nominal and pronominal expressions are D-expressions – i.e. projections of an (overt or null) D constituent – an assumption widely referred to as the DP hypothesis. Indeed, the DP hypothesis can be further extended if we follow Freidin and Vergnaud (2001) in supposing that a pronoun like they (if used to refer to linguists) in a sentence such as:

is a DP comprising a head determiner they with a noun complement linguists which is given a null spellout in the PF component, as shown in (114) below:

However, Radford (1993) argued that while a phrasal analysis along the lines of (114) may be appropriate for some pronouns (e.g. which?), other pronouns (e.g. who?) seem to be simple heads. This difference of status is reflected in syntactic differences between the two: e.g. who can be modified by else but which and overtly phrasal expressions cannot (cf. Who else? ∗Which else? ∗How many people else?), and who can be positioned immediately in front of a preposition, but which and phrases cannot (cf. Who to? ∗Which to? ∗How many people to?). While an analysis like (114) may be appropriate for some types of pronoun in some languages (see Wiltschko 2002), it does not seem appropriate for English personal pronouns.

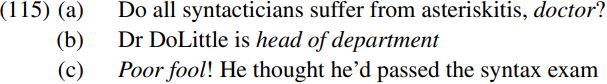

We have argued that canonical nominal expressions are DPs headed by an (overt or null) determiner. However, there is evidence that this is true only of nominal expressions used as arguments(i.e. nominals used as the subject or complement of a predicate), not of non-argument nominals (e.g. nominals which have a vocative, predicative or exclamative use). More specifically (as Longobardi 1994 argues), non-argument nominals such as those italicized in (115) below can be N-projections lacking a determiner:

The italicized nominal expression serves a vocative function (i.e. is used to address someone) in (115a), a predicative function in (115b) (in that the property of being head of department is predicated of the unfortunate Dr DoLittle), and an exclamative function in (115c). Each of the italicized nominals in (115) is headed by a singular count noun (doctor/head/fool): in spite of the fact that such nouns require an overt determiner when used as arguments, here they function as non-arguments and are used without any determiner. This suggests that non-argument nominals can be N-expressions, whereas argument nominals are always D-expressions.

Chomsky (1999, fn. 10) maintains that only referential nominal arguments (i.e. nominal arguments which are referring expressions) have the status of true DPs, not ‘nonspecifics, quantified and predicate nominals, etc.’ If so, bare nominals with a quantificational interpretation would more appropriately be analyzed as QPs headed by a null quantifier: on this view, the noun eggs in (110c) I had eggs for breakfast would be a QP headed by a null partitive quantifier (rather than a DP headed by a null determiner).

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)