Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Explaining what moves where

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

202-6

9-1-2023

1742

Explaining what moves where

Our discussion looked at wh-movement in interrogative complement clauses which involve movement of a wh-word (rather than a wh-phrase), and which don’t involve auxiliary inversion. But now consider how we handle the syntax of main-clause wh-questions like (34) below which involve both movement of a wh-phrase and movement of an auxiliary:

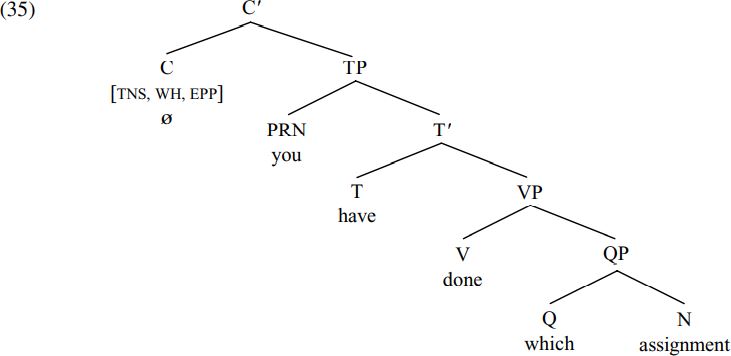

Let’s suppose that the derivation of (34) proceeds as follows. The quantifier which merges with the noun assignment to form the QP which assignment. This in turn is merged with the verb done to form the VP done which assignment. The resulting VP is subsequently merged with the present-tense auxiliary have to form the T-bar have done which assignment, which is itself merged with the pronoun you to form the TP you have done which assignment. TP is then merged with a null interrogative C. Since (34) is a wh-question, C will carry a [WH] feature and an [EPP] feature. Since (34) is a main-clause question, we can assume that C also carries a [TNS] feature which triggers movement of a tensed auxiliary from T to C. Given these assumptions, merging C with the TP you have done which assignment will derive the following structure:

At first sight, the derivation might seem straightforward from this point on: the [TNS] feature of C attracts the present-tense auxiliary have to attach to a null question affix in C; the [WH, EPP] features of C trigger movement of the wh-expression which assignment to the specifier position within CP. Assuming that all the features of C are deleted (and thereby inactivated) once their requirements are satisfied, the relevant movement operations will derive the structure shown in simplified form below:

Since the resulting sentence (34) Which assignment have you done? is grammatical, things appear to work out exactly as required.

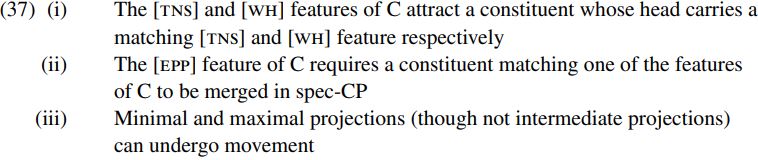

But if we probe a little deeper, we’ll see that there are a number of questions raised by the derivation outlined above. The core assumptions underlying it are the following

But while the assumptions made in (37) are perfectly compatible with the derivation assumed in (36), they raise important questions about what kind of constituent moves to what kind of position and why.

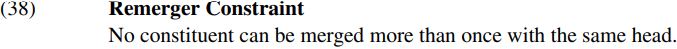

One such question is why the [TNS] feature of C in (35) attracts [T have] rather than [TP you have done which assignment]. We can offer a principled answer to this question by supposing that a head which carries a feature [F] can freely attract either a minimal or a maximal projection carrying [F], but that UG principles rule out certain possibilities. From this perspective, we would expect that the [TNS] feature of C can in principle attract either T or TP (and indeed both are equally close to C in terms of the definition of closeness in (32) above), and if in practice C cannot attract TP, this is because some UG principle rules out this possibility. One reason why C cannot attract its TP complement may be that movement is an operation by which a head attracts (and is thereby merged with) a constituent which it is not already merged with. Since TP is already merged with C by virtue of being the complement of C, it follows that C cannot attract TP. The tacit assumption underlying our reasoning here is that UG incorporates a principle such as the following:

As we saw earlier, [TP you have done which assignment] is initially merged with C at the stage of derivation when the structure shown in (35) above is formed. To subsequently move TP into spec-CP would involve merging TP as the specifier of C – and this would violate the Remerger Constraint (38), since it would mean that TP was initially merged with C as its complement, and subsequently remerged with C as its specifier. By contrast, the Remerger Constraint would not prevent C from attracting [T have], since have is not merged with C prior to T-to-C movement: on the contrary, have was initially merged with its VP complement done which assignment and its pronoun specifier you, so that merging (a copy of) have with C does not violate the constraint against remerger. In short, we can account for why C attracts T rather than TP in terms of a UG principle like (38) barring remerger operations.

A follow-up question is why a tensed auxiliary attracted by C moves into C rather than into spec-CP. A plausible answer to this question is that UG principles determine the landing site of moved constituents (i.e. determine where they end up being positioned). For concreteness, let’s assume that UG incorporates a principle along the lines of (39) below:

(39i) would mean that the head T constituent of TP (by virtue of being a minimal projection) can only move to the head C position of CP, not to the specifier position within CP. (Chomsky 1995, p. 253 offers an alternative account based on chain uniformity, and Carnie 2000 discusses attendant problems.)

Now consider the question of why the [WH] feature of C attracts the QP which assignment rather than the Q which. Given our earlier assumptions, we’d expect that the [WH] feature carried by C can in principle attract either a wh-word or a wh-phrase. However, the [EPP] feature carried by C requires C to project a specifier, and (39ii) tells us that a specifier position can only be filled by a maximal projection. Since we have already seen that the Remerger Constraint (38) prevents C from attracting TP to move to spec-CP, the only way of satisfying the [EPP] requirement is for a wh-constituent to be moved into spec-CP; and since (39ii) tells us that only a maximal projection can occupy a specifier position, it follows that the [WH] feature of C attracts a wh-marked maximal projection like which assignment to move into spec-CP, not a wh-marked minimal projection like which. (Note, however, that the story told here for English needs to be modified for languages which allow certain types of wh-word to move to C, as would seem to be the case for Polish data in Borsley 2002, German data in Kathol 2001, and North Norwegian data in Radford 1994: it may be that C in such languages has an [EDGE] feature requiring a wh-expression to move to the edge of C rather than an [EPP] feature requiring a wh-expression to move to spec-CP.)

The story told above assumes that UG principles like the Remerger Constraint (38) and the Constituent Structure Constraint (39) determine that the [TNS] feature of C attracts movement of a tensed auxiliary to C, and that the [WH, EPP] features of C attract movement of a whmax (i.e. a wh-marked maximal projection) to spec-CP. However, an entirely different approach to the problem of accounting for why the [TNS] and [WH] features of C attract different types of constituent to move to different positions in English is to posit that they are different types of feature which trigger different types of movement operation in different components of the grammar. For example, if the [TNS] feature on C is essentially affixal in nature, we could conclude that head movement operations like T-to-C movement are intrinsically morphological in nature (in that they are designed to provide an affix with a host), and hence take place in the PF component rather than the syntactic component – a possibility explored by Chomsky (1999, pp. 30–1). Chomsky notes that some evidence in support of such a hypothesis comes from the fact that head movement has rather different properties from typical syntactic movement operations like wh-movement. For example, head movement can attract only heads whereas wh-movement can attract maximal projections; head movement is a strictly local operation (whereby a head can attract the head of its complement), whereas wh-movement can attract more distant constituents (e.g. C can attract a wh-constituent which originates within a lower clause, as in (30) and (33) above); head movement involves a form of affixation operation by which one head is affixed to another (forming a compound head), whereas wh-movement is a merger operation by which a moved constituent is merged as the specifier of C; and conversely wh-movement has an effect on semantic interpretation (in that it creates an operator-variable configuration as we noted in relation to (21) above), whereas auxiliary inversion does not. These differences (Chomsky reasons) suggest that features like the [WH] feature of C are syntactic features triggering movement of a maximal projection in the syntax, whereas features like the [TNS] feature of C are morphological features triggering movement of a minimal projection in the PF component. (See Boeckx and Stjepanovi´c 2001 for an additional argument for head movement being a PF operation, and Baltin 2002 for a rebuttal.)

Perceptive though Chomsky’s observations are, they are suggestive rather than conclusive (see Embick and Noyer 2001 for a sceptical view). For example, his claim that head movement is a PF operation because it has no effect on semantic interpretation has little force if we assume that the semantic component interprets the tense properties of clauses by looking at the tense properties of the head T constituent of TP – and cares little whether what is in T is an overt auxiliary or a null copy of a moved auxiliary. Likewise, the argument that head movement is subject to a strict locality constraint like HMC is called into question by Hagstrom’s (1998) analysis of wh-questions in wh-in-situ languages (like Japanese, Okinawan, Navajo and Sinhala) in which he claims that they involve long-distance head movement of a question particle to C. Hagstrom proposes to abandon HMC, and argues that the apparent locality of head movement is an artefact of the Attract Closest Principle/ACP (31). On this view, local (successive-cyclic) movement of the verb say from V to T to C in a Shakespearean sentence such as:

will be a consequence of ACP rather than HMC. For example, if T has a strong V-feature and C has a strong T-feature, T will attract the closest verb (i.e. the head V said of the VP said what) to move to T, and C will attract the closest tensed head (i.e. the head T constituent of TP, with T containing the moved verb said at the relevant stage of derivation) to move to C – thereby guaranteeing local head movement without the need for positing HMC. In short, the question of whether head movement is a syntactic operation (as argued by Roberts 2002) or a PF operation (as argued by Chomsky 1999) or has facets of both (as argued by Zwart 2001) is one which remains open at present.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)