Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Pied-piping

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

211-6

10-1-2023

2862

Pied-piping

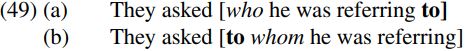

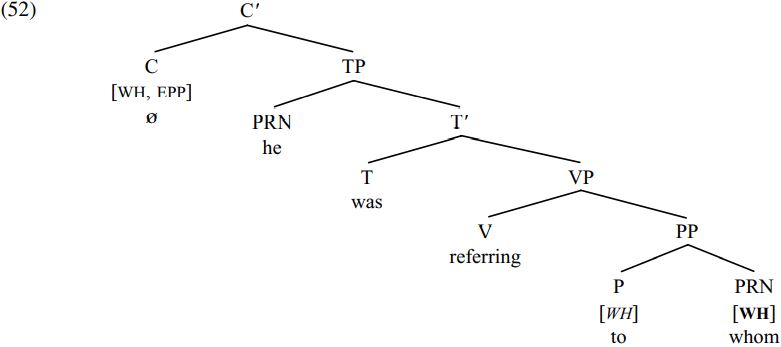

Our discussion of wh-movement in structures like (26/28) suggested that a C carrying [WH, EPP] features attracts a constituent headed by a wh-word to move to spec-CP. An interesting problem posed by this assumption is how we account for what happens in clauses like those bracketed in (49) below where an (italicized) wh-expression is the complement of a (bold-printed) preposition:

In these examples, the wh-pronoun who(m) is the complement of the preposition to (whom being the accusative form of the pronoun in formal styles, who in other styles). In informal styles, the wh-pronoun who is preposed on its own, leaving the preposition to stranded or orphaned at the end of the bracketed complement clause – as in (49a). However, in formal styles, the preposition to is pied-piped (i.e. dragged) along with the wh-pronoun whom, so that the whole PP to whom moves to spec-CP position within the bracketed clause – as in (49b). (The pied-piping metaphor was coined by Ross 1967, based on a traditional fairy story in which the pied-piper in the village of Hamelin enticed a group of children to follow him out of a rat-infested village by playing his pipe.)

Given the assumptions we have made hitherto, the bracketed interrogative complement clause in (49a) will be derived as follows. The preposition to merges with its pronoun complement who to form the PP to who. This in turn is merged with the verb referring to form the VP referring to who. This VP is then merged with the past-tense auxiliary was, forming the T-bar was referring to who which in turn is merged with its subject he to form the TP he was referring to who. Merging the resulting TP with a null interrogative complementizer carrying [WH, EPP] features will derive the structure shown in (50) below:

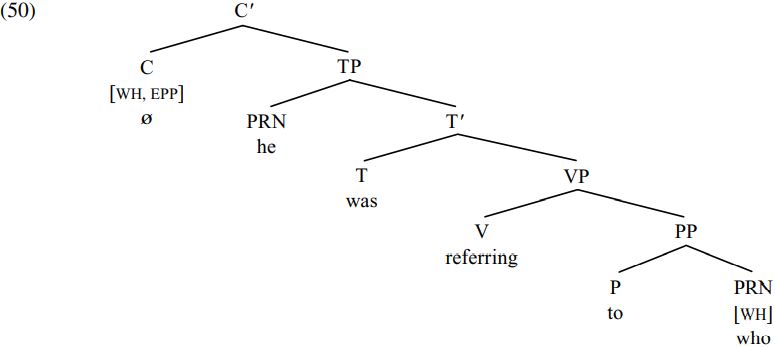

The [WH, EPP] features of C attract a wh-marked maximal projection to move to the specifier position within CP. Since the only wh-marked maximal projection in (50) is the wh-pronoun who (which is a maximal projection by virtue of being the largest expression headed by who) it follows that who will move to spec-CP (thereby deleting the [WH] and [EPP] features of C), so deriving the CP shown in simplified form below:

And (51) is the structure of the bracketed interrogative complement clause in (49a).

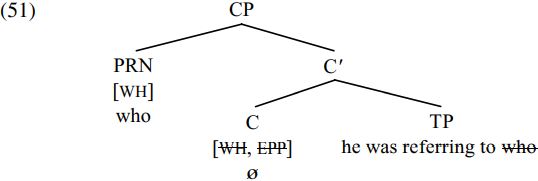

But what about the derivation of the bracketed complement clause in the formal-style sentence (49b) They asked [to whom he was referring]? How can we account for the fact that the whole prepositional phrase to whom is moved to the front of the complement clause in (49b), with the preposition to being pied-piped along with the wh-pronoun whom? One approach to preposition pied-piping is to assume that the head P to of the PP to whom carries a wh-feature which it acquires from the wh-word whom via some form of feature-copying: by virtue of being a projection of to, the PP to whom will then carry the same wh-feature as its head preposition to, and so can be attracted by the [WH] feature of C. This is a traditional idea underlying metaphorical claims in earlier work that a wh-feature can percolate from a complement onto a preposition, or conversely (to use the more funereal metaphor adopted by Sag 1997) that a preposition can inherit a wh-feature from its complement. Let’s suppose that this kind of feature-copying comes about via merger, and that (in formal styles of English) a preposition is wh-marked when merged with a wh-complement (in the sense that the wh-feature on the pronoun is thereby copied onto the preposition).

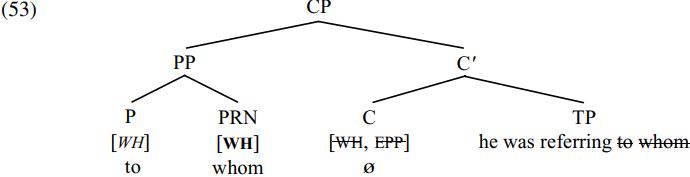

In the light of this assumption, we can return to consider the derivation of the formal-style bracketed complement clause in (49b) They asked [to whom he was referring]. Since the complement of the preposition to in (49b) is the pronoun whom which contains a wh-feature, to will inherit this wh-feature via merger with whom in formal styles, and if it does, the bracketed complement clause in (49b) will have the structure shown in (52) below at the stage of derivation when C merges with its TP complement:

The PP to whom will consequently carry a [WH] feature (not shown here), by virtue of being the maximal projection of the wh-marked preposition to. Given the Attract Closest Principle/ACP, the [WH] feature of C will attract the closest wh-marked maximal projection c-commanded by C. Since the PP to whom is closer to C than the PRN whom, this means that the wh-marked PP to whom moves to spec-CP, so deriving the structure shown in simplified form below:

If wh-copying (between a preposition and its wh-object) and use of whom are both associated with formal styles of English, it follows that preposition pied-piping will occur with whom but not who. (But see Lasnik and Sobin 2000 for fuller discussion of the use of whom in present-day English.) Some evidence which might seem to support a feature-copying analysis of pied-piping comes from the observation made by Kishimoto (1992) that in Sinhala, a PP comprising a P and a wh-word has the question-particle də suffixed to the (P head of the) overall PP, even though the relevant particle normally attaches to a wh-word: if də attaches to a wh-marked constituent, this would be consistent with the view that the wh-feature on the wh-word percolates up to the head P of PP. (However, see Hagstrom 1998 for an alternative account.)

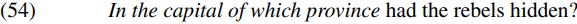

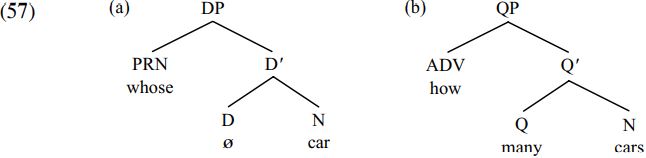

The feature-copying analysis of pied-piping outlined above has interesting ramifications for more complex cases of pied-piping, e.g. in sentences such as

If (as we assumed in (37i) above) only a constituent with a wh-marked head can be attracted byaC carrying [WH, EPP] features, the story which we will have to tell about how the string in the capital of comes to be pied-piped along with the wh-QP which province will be the following. The preposition of is wh-marked by merger with its wh-complement which province, and the PP of which province thereby comes to carry the same wh-feature as its head. The noun capital is in turn wh-marked by merger with its wh-complement of which province, and the NP capital of which province carries the same wh-feature as its head. The determiner the is then wh-marked by merger with its wh-complement capital of which province, and the DP the capital of which province is thereby wh-marked as well. The preposition in is subsequently wh-marked by merger with its wh-complement the capital of which province, with the result that the whole PP in the capital of which province is wh-marked – and hence can be attracted by a C with a [WH] feature.

However, there are aspects of this feature-copying analysis which seem questionable. For example, the assumption that the wh-feature on the word which (via a series of merger operations) percolates onto of, capital, the and in raises the question of why none of these words shows any visible sign of being wh-marked. The proliferation of wh-features entailed by the analysis seems not only morphologically unmotivated but also (from the Minimalist perspective of trying to eliminate unnecessary descriptive apparatus) conceptually unattractive. More-over, if a [WH] feature can percolate from a complement to a head via merger, there seems nothing to prevent the [WH] feature on the preposition in spreading onto the verb hidden in (54) and thence onto its VP projection hidden in the capital of which province, so triggering wh-movement of the VP headed by hidden and wrongly predicting that sentences like (55) below are ungrammatical:

Clearly, constraints have to be put on wh-percolation, but the nature of these constraints is not clear. For example, is it just nominal and prepositional heads which can be wh-marked via merger with a wh-complement – and if so, why?

Furthermore, it is by no means clear that the core assumption underlying the analysis (namely that a wh-marked C attracts a constituent with a wh-marked head) can be defended in relation to sentences like:

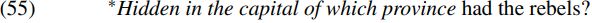

At first sight, there might seem to be no problem here: after all, why not simply assume that whose in (56a) is the head of whose car and that how in (56b) is the head of how many cars and hence that wh-movement targets a maximal projection headed by a wh-word like whose/how? However, the problem is that whose cannot be the head of whose car because whose carries genitive case and yet whose car is the complement of the transitive verb borrow and so must be accusative; and likewise how cannot be the head of how many cars because how is a degree adverb and yet how many cars is not an adverbial phrase but rather a quantifier phrase. It seems more plausible to take whose and how to be the specifiers of the expressions containing them, so that the relevant expressions have the structures shown in simplified form below:

(57a) is adapted from Chomsky (1995, p. 263) and assumes that the head of the overall DP is a null definite determiner (a null counterpart of the D constituent the), so that (57a) has an interpretation paraphraseable as ‘the car belonging to who’. (57b) claims that the overall structure is a plural nominal expression headed by the quantifier many, with cars serving as its complement and how as its specifier.

The crucial aspect of the analyses in (57a,b) from our perspective is that the wh-word whose/how is not the head of the overall DP/QP structure, but rather its specifier. This challenges the core assumption (37i) underlying the feature-copying analysis of pied-piping – namely that a wh-marked C attracts a constituent with a wh-marked head. Such an assumption would provide us with no account of why the overall nominals whose car and how many cars undergo wh-movement in (56), and not who and how on their own. Note that we cannot simply suppose that a phrase is a projection of the features carried by its specifier as well as those carried by its head, since this would wrongly predict (e.g.) that whose car (by virtue of having a genitive specifier) should be genitive – when it is accusative as used in (56a).

Let’s therefore explore an entirely different approach to pied-piping – one which dispenses with the feature-copying apparatus we used above. Chomsky (1995, pp. 262–5) offers such an approach based on a principle which we can outline informally as follows:

This means that the [WH] feature on C attracts the smallest constituent containing a word carrying a [WH] feature whose movement will lead to a well-formed sentence. In the case of a sentence like (34) Which assignment have you done? the smallest constituent carrying a wh-feature is the wh-word which that is the head Q of the QP which assignment, and hence a minimal projection; but since the [EPP] feature of C requires C to project a specifier, and the Constituent Structure Constraint (39ii) tells us that only a maximal projection can occupy a specifier position, which cannot move on its own, so the next smallest constituent containing which has to move, namely the QP which assignment. Since this is a maximal projection, it can move to spec-CP without violation of any constraints.

Now consider how the convergence account handles preposition pied-piping in the bracketed relative clauses in (49a) They asked [who he was referring to] and (49b) They asked [to whom he was referring]. These would both have the structure (50) above at the point where C is merged with its TP complement, and the [WH] feature of C would attract the smallest constituent containing a wh-word which will ensure convergence. Since the smallest such constituent is the wh-pronoun who, it is who which is preposed in informal-style relative-clause structures like who he was referring to in (49a). But let’s suppose that in formal styles of English, there is a Stranding Constraint which ‘bars preposition stranding’ (Chomsky 1995, p. 264). This means that (in formal styles) the wh-pronoun whom cannot be preposed on its own, since this would lead to violation of the Stranding Constraint. So, instead, the next smallest constituent containing the wh-word is preposed, namely the PP to whom.

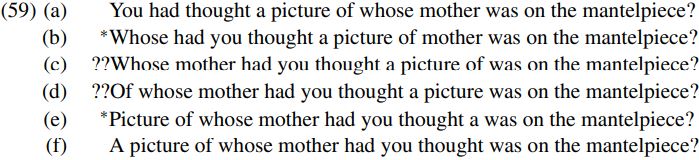

The assumption that pied-piping of additional material along with a wh-word occurs only when it is forced by the need to ensure convergence offers us an interesting account of pied-piping in sentences such as (59b–e) below, which are wh-movement counterparts of the wh-in-situ question in (59a):

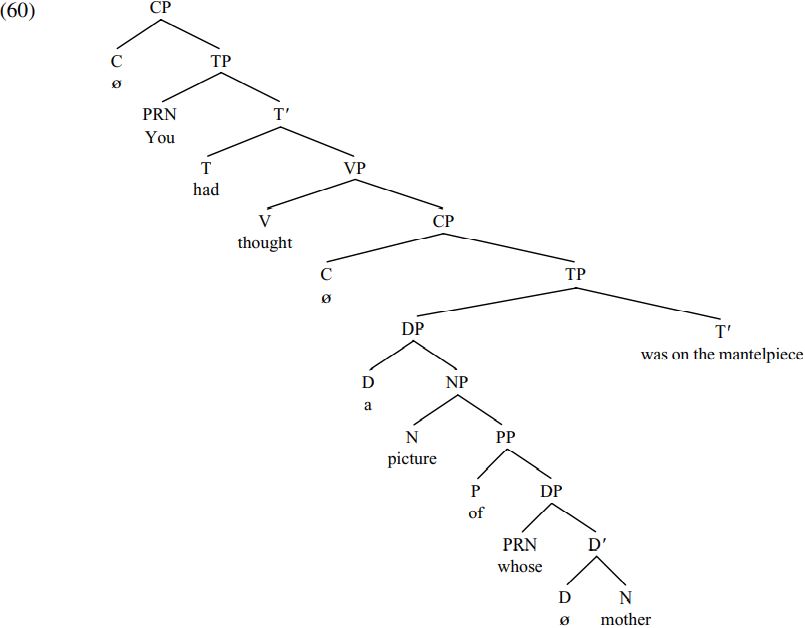

At the stage of derivation where the main-clause C is merged with its TP complement, (59b–f) will have the structure shown in simplified form below (if we take the indefinite article a to be a determiner rather than a quantifier):

The main-clause C constituent at the top of the tree contains an affixal [TNS] feature which attracts the tensed auxiliary had to move to C, and [WH, EPP] features which attract the smallest convergent constituent containing a wh-word to move to spec-CP. Let’s look carefully at what happens.

Movement of the pronoun whose on its own in (59b) leads to ungrammaticality, and the obvious question to ask is why this should be. (Part of) the answer lies in a constraint identified by Ross (1967), termed the Left Branch Condition, which we can paraphrase loosely as in (61) below:

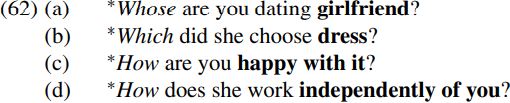

(The term nominal expression can be taken to refer to DP/QP. Within an order-free theory of syntax, the term leftmost should be reformulated in terms of some hierarchical counterpart like daughter – but this is a detail we set aside here.) LBC accounts for the ungrammaticality of structures such as those below in English (where the italicized wh-word is intended to modify the bold-printed expression):

(The term nominal expression can be taken to refer to DP/QP. Within an order-free theory of syntax, the term leftmost should be reformulated in terms of some hierarchical counterpart like daughter – but this is a detail we set aside here.) LBC accounts for the ungrammaticality of structures such as those below in English (where the italicized wh-word is intended to modify the bold-printed expression):

(Irrelevantly, (62c,d) are grammatical if how is construed as an independent adverb which does not modify the bold-printed material.) Since LBC blocks extraction of whose on its own in (60), the Convergence Principle (58) tells us to try preposing the next smallest constituent containing whose, namely the DP whose mother. But movement of this DP is not possible either, as we see from the ungrammaticality of (59c). How come?

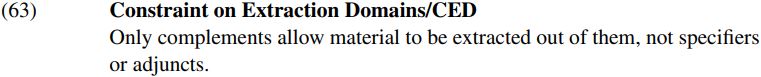

One reason for the ungrammaticality of (59c) is that it violates a constraint on movement operations posited by Huang (1982) which we can outline informally as follows:

We can illustrate Huang’s CED constraint in terms of the following contrasts:

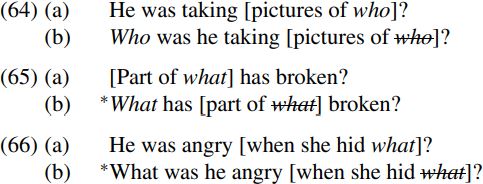

(64a), (65a) and (66a) are echo questions in which the wh-pronoun who/what remains in situ, while (64b), (65b) and (66b) are their wh-movement counter-parts. In (64), who is extracted out of a bracketed nominal expression which is the complement of the verb taking, and yields the grammatical outcome (64b) since there is no violation of CED (extraction out of complement expressions being permitted by CED). By contrast, in (65) what is extracted out of a bracketed expression which is the subject (and hence specifier) of the auxiliary has, and since CED blocks extraction out of specifiers, the resulting sentence (65b) is ungrammatical. Likewise in (66), what is extracted out of a bracketed adjunct clause, and since CED blocks extraction out of adjuncts, (66b) is ungrammatical. (See Nunes and Uriagereka 2000 and Sabel 2002 for attempts to devise a Minimalist account of CED effects.)

In the light of Huang’s CED constraint, the reason why extraction of whose mother leads to ungrammaticality in (59c) should be clear. This is because whose mother is contained within [DP a picture of whose ø mother] in (60), and since this DP is the specifier of the T-bar was on the mantelpiece, CED blocks extraction of any material out of this DP. As should be obvious, movement of whose on its own in (59b) will also violate CED (as well as LBC) – hence (59b) shows a higher degree of ill-formedness (by virtue of violating both CED and LBC) than (59c) (which violates only CED).

In conformity with the Convergence Principle, we therefore try and prepose the next smallest constituent containing whose in (60), namely the PP of whose ø mother. But extraction of this PP out of the containing [DP a picture of whose ø mother] is again blocked by CED. Accordingly, we try and prepose the next smallest constituent containing whose, namely [NP picture of whose ø mother]: once again, however, this is blocked by CED – as well as by the Functional Head Constraint/FHC which forbids extraction of the complement of a functional head like D or C (and hence blocks extraction of the complement of the determiner a). Because it violates two constraints (CED and FHC), (59e) induces a higher degree of ungrammaticality than (59d) (which violates only CED). We therefore prepose the next smallest constituent containing whose, namely [DP a picture of whose ø mother]. This is permitted by CED, since CED only blocks extraction out of a specifier, not extraction of a specifier. Since this DP is the smallest maximal projection containing whose which can be preposed without violating any constraint, the convergence analysis correctly predicts the grammaticality of (59f) A picture of whose mother had you thought was on the mantelpiece?

We began our analysis of pied-piping by assuming that the [WH] feature on C can only attract a maximal projection carrying a wh-feature, and that a phrase only carries a wh-feature if it has a wh-head. We saw that one analysis of pied-piping consistent with this assumption is that it is the result of a feature-copying operation by which a head acquires a copy of a wh-feature carried by a constituent which it merges with. However, we noted that this account runs into problems in relation to wh-movement structures where the wh-word is the specifier of the head containing it. We sketched Chomsky’s alternative convergence view under which the [WH] feature on C attracts the smallest constituent containing a wh-word whose movement will lead to a convergent derivation.

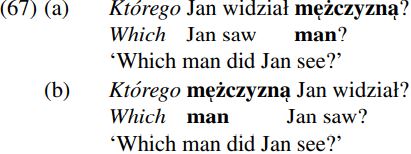

The convergence view is not entirely without posing problems however, as we can illustrate in terms of the following Polish examples kindly provided by Bob Borsley:

If convergence requires us to move the smallest wh-marked constituent, then the fact that movement of the quantifier kt’orego ‘which’ on its own is permitted would lead us to suppose that it should not be possible to move the larger QP

‘which man?’. It is not clear how such data can best be dealt with under the convergence account: perhaps (as briefly mentioned in a parenthetical) Polish allows either movement of a wh-head to C or movement of a wh-phrase to spec-CP, and hence permits either the smallest wh-marked head to move to C, or the smallest wh-phrase to move to spec-CP. Other solutions can be envisaged, but a book on English syntax is not the place to speculate on Polish syntax.

‘which man?’. It is not clear how such data can best be dealt with under the convergence account: perhaps (as briefly mentioned in a parenthetical) Polish allows either movement of a wh-head to C or movement of a wh-phrase to spec-CP, and hence permits either the smallest wh-marked head to move to C, or the smallest wh-phrase to move to spec-CP. Other solutions can be envisaged, but a book on English syntax is not the place to speculate on Polish syntax.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)