Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Subjects in Belfast English

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

241-7

21-1-2023

1864

Subjects in Belfast English

Let’s begin our discussion of the syntax of subjects by looking at some interesting data from Belfast English (kindly supplied to me by Alison Henry). Alongside Standard English constructions like (1a,b) below:

Belfast English also has structures like (2a,b):

Sentences like (2a,b) are called expletive structures because they contain the expletive pronoun there. (The fact that there is not a locative pronoun in this kind of use is shown by the impossibility of replacing it by locative here or questioning it by the interrogative locative where? or contrastively focusing it by assigning it contrastive stress.) For the time being, let’s focus on the derivation of Belfast English sentences like (2a,b) before turning to consider the derivation of Standard English sentences like (1a,b).

One question to ask about the sentences in (2a,b) is where the expletive pronoun there is positioned. Since there immediately precedes the tensed auxiliary should/have, a reasonable conjecture is that there is the subject of should/have and hence occupies the spec-TP position. If this is so, we’d expect to find that the (bold-printed) auxiliary can move in front of the (italicized) expletive subject (via T-to-C movement) in questions – and this is indeed the case in Belfast English, as the sentences in (3) below illustrate:

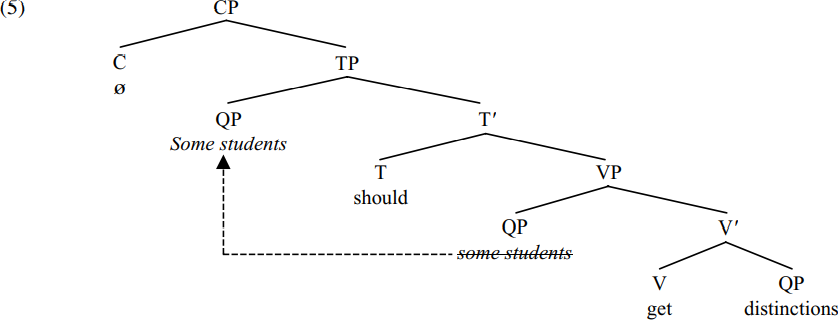

But what position is occupied by the underlined quantified expressions some students/lots of students in (3)? Since they immediately precede the verbs get/missed and since subjects precede verbs, it seems reasonable to conclude that the expressions some students/lots of students function as the subjects of the verbs get/missed and (since subjects are typically specifiers) occupy spec-VP (i.e. specifier position within VP). If these assumptions are correct, (2a) will have the structure (4) below (simplified by not showing the internal structure of the expressions some students/distinctions: we can take both of these to be QP/Quantifier Phrase expressions, headed by the overt quantifier some in one case and by a null quantifier [Q ø ] in the other):

The analysis in (4) claims that the sentence contains two subjects/specifiers: there is the specifier (and syntactic subject) of should, and some students is the specifier (and semantic subject) of get.

Given the assumptions in (4), sentence (2a) will be derived as follows. The noun distinctions merges with a null quantifier [Q ø ] to form the QP ø distinctions. By virtue of being the complement of the verb get, this QP is merged with the V get to form the V-bar (incomplete verb expression) get ø distinctions. The resulting V-bar is then merged with the subject of get, namely the QP some students (itself formed by merging the quantifier some with the noun students), so deriving the VP some students get ø distinctions. This VP is in turn merged with the tense auxiliary should, forming the T-bar should some students get ø distinctions. Let’s suppose that a finite T has an [EPP] feature requiring it to have a specifier with person/number properties. In sentences like (2a,b) in Belfast English, the requirement for T to have such a specifier can be satisfied by merging expletive there with the T-bar should some students get ø distinctions, so forming the TP There should some students get ø distinctions. The resulting TP is then merged with a null declarative complementizer, forming the CP shown in (4) above.

But what about the derivation of the corresponding Standard English sentence (1a) Some students should get distinctions? Let’s suppose that the derivation of (1a) runs parallel to the derivation of (2a) until the point where the auxiliary should merges with the VP some students get ø distinctions to form the T-bar should some students get ø distinctions. As before, let’s assume that [T should] has an [EPP] feature requiring it to project a structural subject/specifier. But let’s also suppose that the requirement for [T should] to have a specifier of its own cannot be satisfied by merging expletive there in spec-TP because in standard varieties of English there can generally only occur in structures containing an intransitive verb like be, become, exist, occur, arise, remain etc. Instead, the [EPP]requirement for T to have a subject with person/number properties is satisfied by moving the subject some students from its original position in spec-VP into a new position in spec-TP, in the manner shown by the arrows below:

Since spec-TP is an A-position which can only be occupied by an argument expression, the kind of movement operation illustrated by the dotted arrow in (5) is called A-movement.

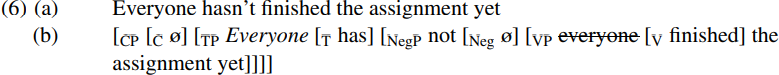

Given the arguments that head movement and A-bar movement are composite operations involving copying and deletion, we would expect the same to be true of A-movement. One piece of evidence in support of a copying analysis of A-movement comes from scope facts in relation to sentences such as (6a) below, which will have the syntactic structure shown in simplified form in (6b) if everyone originates as the subject of the verb finished and is then raised up (by A-movement) to become the subject of the present-tense auxiliary HAVE:

For many speakers, sentences like (6a) are ambiguous between (i) a reading on which the quantifier expression everyone has scope over not so that the sentence means much the same as ‘Everyone is in the position of not having finished the assignment yet’, and (ii) another reading on which everyone falls within the scope of not (so that the sentence means much the same as ‘Not everyone has finished the assignment yet’). We can account for this scope ambiguity in a principled fashion if we suppose that A-movement involves copying, that scope is defined in terms of c-command (so that a scope-bearing constituent has scope over constituents which it c-commands), and that the scope of a universally quantified expression like everyone in negative structures like (6b) can be determined either in relation to the initial position of everyone or in relation to its final position. In (6b) everyone is initially merged in a position (marked by strikethrough) in which it is c-commanded by (and so falls within the scope of) not; but via A-movement it ends up in an (italicized) position in which it c-commands (and so has scope over) not. The scope ambiguity in (6a) therefore reflects the two different positions occupied by everyone in the course of the derivation. (See Lebeaux 1995, Hornstein 1995, Romero 1997, Sauerland 1998, Lasnik 1998/1999, Fox 2000, and Boeckx 2000, 2001 for discussion of scope in A-movement structures.)

The claim that (non-expletive) subjects like some students/lots of students in sentences like (1a, b) originate internally within the VP containing the relevant verb (and from there move into spec-TP in sentences like (1a, b) above) is known in the relevant literature as the VP-Internal Subject Hypothesis (= VPISH), and has been widely adopted in research since the mid 1980s. An extensive body of evidence was adduced in support of the hypothesis from a variety of sources and languages in the 1980s and early 1990s, e.g. in Kitagawa (1986), Speas (1986), Contreras (1987), Zagona (1987), Kuroda (1988), Sportiche (1988), Rosen (1990), Ernst (1991), Koopman and Sportiche (1991), Woolford (1991), Burton and Grimshaw (1992), McNally (1992), Guilfoyle, Hung and Travis (1992), and Huang (1993). Since then, it has become a standard analysis. We will look at some of the evidence in support of VPISH.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)