VP shells in transitive, unergative, unaccusative, raising and locative inversion structures

We looked at how to deal with the complements of three-place transitive predicates. But now we turn to look at the complements of simple (two-place) transitive predicates (which have subject and object arguments) like read in (66) below:

Chomsky (1995) proposes a light-verb analysis of two-place transitive predicates under which (66) would (at the end of the vP cycle) have a structure along the lines of (67) below (with the arrow showing movement of the verb read from V to adjoin to a null light verb in v):

That is, read would originate as the head V of VP, and would then be raised to adjoin to a null agentive light verb ø. (A different account of transitive complements as VP-specifiers is offered in Stroik 1990 and Bowers 1993.)

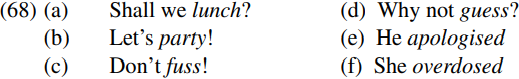

Chomsky’s light-verb analysis of two-place transitive predicates can be extended in an interesting way to handle the syntax of a class of verbs which are known as unergative predicates. These are verbs like those italicized in (68) below which have agentive subjects, but which appear to have no complement:

Such verbs pose obvious problems for our assumption that agentive subjects originate as specifiers and merge with an intermediate verbal projection which is itself formed by merger of a verb with its complement. The reason should be obvious – namely that unergative verbs like those italicized in (68) appear to have no complements. However, it is interesting to note that unergative verbs often have close paraphrases involving an overt light verb (i.e. a verb such as have/make/take etc. which has little semantic content of its own in the relevant use) and a nominal complement:

This suggests a way of overcoming the problem posed by unergative verbs – namely to suppose (following Baker 1988 and Hale and Keyser 1993) that unergative verbs are formed by incorporation of a complement into an abstract light verb. This would mean (for example) that the verb lunch in (68a) is an implicitly transitive verb, formed by incorporating the noun lunch into an abstract light verb which can be thought of as a null counterpart of have. Since the incorporated object is a simple noun (not a full DP), we can assume (following Baker 1988) that it does not carry case. The VP thereby formed would serve as the complement of an abstract light verb with an external argument (the external argument being we in the case of (68a) above). Under this analysis, unergatives would in effect be transitives with an incorporated object: hence we can account for the fact that (like transitives) unergatives require the use of the perfect auxiliary HAVE in languages (like Italian) with a HAVE/BE contrast in perfect auxiliaries

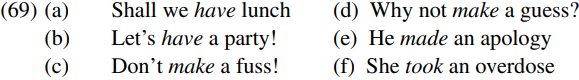

Moreover, there are reasons to suppose that a light-verb analysis is required for unaccusative structures as well, and that the syntax of unaccusative predicates like come/go is rather more complex where we noted Burzio’s claim that the arguments of unaccusative predicates originate as their complements. An immediate problem posed by Burzio’s assumption is how we deal with two-place unaccusative predicates which take two arguments. In this connection, consider unaccusative imperative structures such as the following in (dialect A of) Belfast English (see Henry 1995: note that youse is the plural form of you – corresponding to American English y’all):

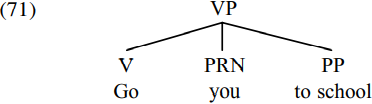

If postverbal arguments of unaccusative predicates are in-situ complements, this means that each of the verbs in (70) must have two complements. But if we make the traditional assumption that complements are sisters of a head, this means that if both you and to school are complements of the verb go in (70a), they must be sisters of go, and hence the VP headed by go must have the (simplified) structure (71) below:

However, a ternary-branching structure such as (71) is obviously incompatible with a framework such as that used here which assumes that the merger operation by which phrases are formed is inherently binary.

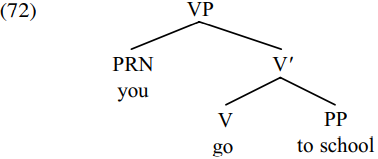

Since analyzing unaccusative subjects in such structures as underlying complements proves problematic, let’s consider whether they might instead be analyzed as specifiers. On this view, we can suppose that the inner VP core of a Belfast English unaccusative imperative structure such as (70a) Go you to school! is not (71) above, but rather (72) below:

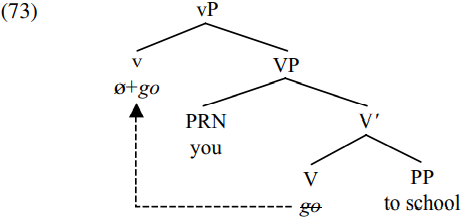

We can then say that it is a property of unaccusative predicates that all their arguments originate within VP. But the problem posed by a structure like (72) is that it provides us with no way of accounting for the fact that unaccusative subjects like you in (70a) Go you to school! surface postverbally. How can we overcome this problem? One answer is the following. Let us suppose that VPs like (72) which are headed by an unaccusative verb are embedded as the complement of a null light verb, and that the unaccusative verb raises to adjoin to the light verb in the manner indicated by the arrow in (73) below:

If (as Alison Henry argues) subjects remain in situ in imperatives in dialect A of Belfast English, the postverbal position of unaccusative subjects in sentences such as (70) can be accounted for straightforwardly. And the shell analysis in (73) is consistent with the assumption that the merger operation by which phrases are formed is intrinsically binary.

Moreover, the shell analysis enables us to provide an interesting account of the position of adverbs like quickly in unaccusative imperatives (in dialect A of Belfast English) such as:

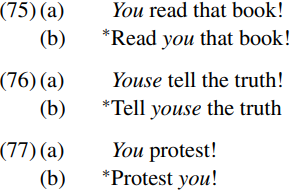

If we suppose that adverbs like quickly are adjuncts which merge with an intermediate verbal projection (i.e. a single-bar projection comprising a verb and its complement), we can say that quickly in (74) is adjoined to the V-bar go to school in (73). What remains to be accounted for (in relation to the syntax of imperative subjects in dialect A of Belfast English) is the fact that subjects of transitive and unergative verbs occur in preverbal (not postverbal) position: cf.

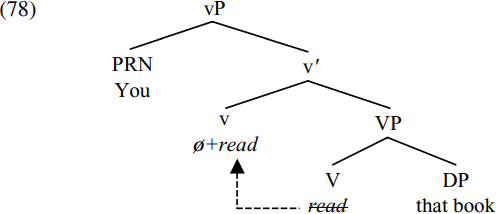

Why should this be? If we assume (as in our discussion of (66) above) that transitive verbs originate as the head V of a VP complement of a null agentive light verb, an imperative such as (75a) will contain a vP with the simplified structure shown in (78) below (where the dotted arrow indicates movement of the verb read to adjoin to the null light verb heading vP):

The AGENT subject you will originate in spec-vP, as the subject of the agentive light verb ø. Even after the verb read adjoins to the null light verb, the subject you will still be positioned in front of the resulting verbal complex ø+read. As should be obvious, we can extend the light-verb analysis from transitive verbs like read to unergative verbs like protest if we assume (as earlier) that such verbs are formed by incorporation of a noun into the verb (so that protest is analyzed as having a similar structure to make (a) protest), and if we assume that unergative subjects (like transitive subjects) originate as specifiers of an agentive light verb.

Given these assumptions, we could then say that the difference between unaccusative subjects and transitive/unergative subjects is that unaccusative subjects originate within VP (as the argument of a lexical verb), whereas transitive/ unergative subjects originate in spec-vP (as the external argument of a light verb). If we hypothesise that verb phrases always contain an outer vP shell headed by a strong (affixal) light verb and an inner VP core headed by a lexical verb, and that lexical verbs always raise from V to v, the postverbal position of unaccusative subjects can be accounted for by positing that the subject remains in situ in such structures. Such a hypothesis will clearly require us to modify our earlier assumptions about the intransitive use of ergative predicates in sentences like (32)–(37) above, and to analyze intransitive ergatives in a parallel fashion to unaccusatives.

The light-verb analysis sketched here also offers us a way of accounting for the fact that in Early Modern English, the perfect auxiliary used with unaccusative verbs was be, whereas that used with transitive and unergative verbs was have. We can account for this by positing that the perfect auxiliary have selected a vP complement headed by a transitive light verb with an external argument, whereas the perfect auxiliary be selected a complement headed by an intransitive light verb with no external argument. The distinction has been lost in present-day English, with perfect have being used with both types of vP complement.

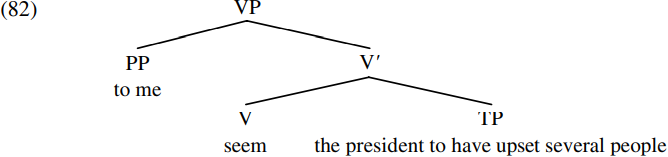

A class of predicates which are related to unaccusatives (in that they project no external argument) are raising predicates like seem. In this connection, consider the syntax of a raising sentence such as:

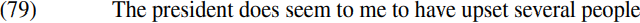

Given the assumptions made here, (79) will be derived as follows. The verb upset merges with its QP complement several people to form the VP upset several people. This in turn merges with a null causative light verb, which (by virtue of being affixal in nature) triggers raising of the verb upset to adjoin to the light verb (as shown by the dotted arrow below); the resulting v-bar merges with its external AGENT argument the president to form the vP in (80) below (paraphraseable informally as ‘The president caused-to-get-upset several people’):

The resulting vP is then merged with the auxiliary have to form an AUXP, and this AUXP is in turn merged with [T to]. If we follow Chomsky (2001) in supposing that T in raising infinitives has an [EPP] feature and an unvalued person feature, the subject the president will be attracted to move to spec-TP, so deriving the structure shown in simplified form below (with the arrow marking A-movement):

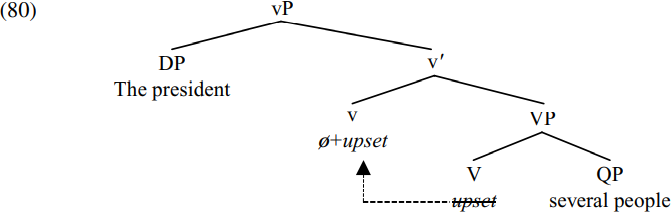

The TP in (81) is then merged as the complement of seem, forming the V-bar seem the president to have upset several people (omitting traces and other empty categories, to make exposition less abstract). Let’s suppose that to me is the EXPERIENCER argument of seem and is merged as the specifier of the resulting V-bar, forming the VP shown in (82) below (once again simplified by not showing traces and other empty categories):

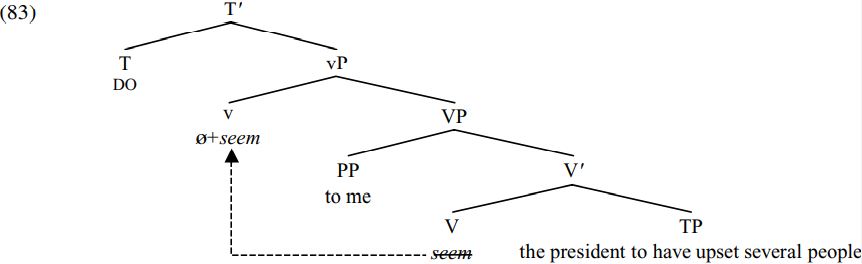

On the assumption that all verb phrases contain an outer vP shell, the VP in (82) will then merge with a null (affixal) light verb, triggering raising of the verb seem to adjoin to the light verb. Merging the resulting vP with a finite T constituent containing (emphatic) DO will derive the structure shown in simplified form below (with the arrow showing the verb movement that took place on the vP cycle):

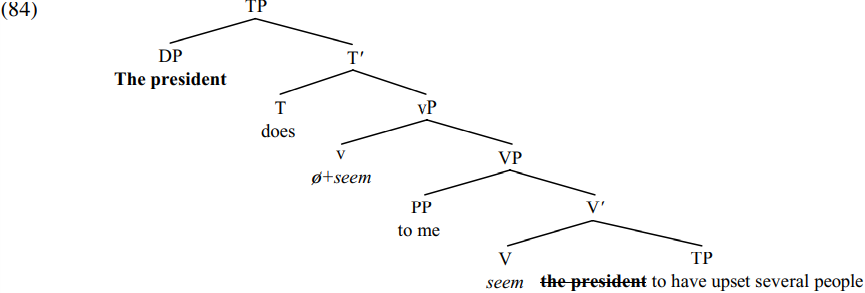

[T DO] serves as a probe looking for an active nominal goal. The Phase Impenetrability Condition (which renders the object of a transitive verb impenetrable to a c-commanding T constituent) makes the nominal several people impenetrable to T, since it is the object of the transitive verb upset: and let’s assume that the pronoun me is likewise inaccessible to T (perhaps because a nominal goal is only active if it has an unvalued case feature, and the case feature of me has already been valued as accusative by the transitive preposition to; or perhaps because me serves as the goal of a closer probe, namely the transitive preposition to). If so, the president (which is active by virtue of having an unvalued case feature) will be the only nominal which can serve as the goal of [T DO] in (83). Accordingly, DO assigns nominative case to the president (and conversely agrees with the president, with DO ultimately being spelled out at PF as does), and the [EPP] and uninterpretable person/number features of DO ensure that the president moves into spec-TP, so deriving the structure shown in simplified form below:

The resulting TP will then be merged with a null declarative complementizer, forming the CP structure associated with (79) The president does seem to me to have upset several people. We can assume that the related sentence (85) below:

has an essentially parallel derivation, except that the verb seem in (85) projects no EXPERIENCER argument, so that the structure formed when seem is merged with its TP complement will not be (82) above, but rather [VP [V seem] [TP the president [T to] have upset several people]].

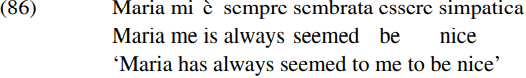

An interesting corollary of the light-verb analysis of raising verbs like seem is that the Italian counterpart of seem is used with the perfect auxiliary essere ‘be’ rather than avere ‘have’ – as we can illustrate in relation to:

(The position of the EXPERIENCER argument mi ‘to me’ in (86) is accounted for by the fact that it is a clitic pronoun, and clitics attach to the left of a finite auxiliary or verb in Italian – in this case attaching to the left of e` ‘is’.) Earlier, we suggested that in languages with the HAVE/BE contrast, HAVE typically selects a vP complement with an external argument, whereas BE selects a vP complement with no external argument. In this context, it is interesting to note (e.g. in relation to structures like (84) above) that the light verb found in clauses containing a raising predicate like seem projects no external argument, and hence would be expected to occur with (the relevant counterpart of) the perfect auxiliary BE in a language with the HAVE/BE contrast. Data such as (86) are thus consistent with the light-verb analysis of raising predicates like seem outlined here. (It should be noted, however, that the HAVE/BE contrast is somewhat more complex than suggested here: see Sorace 2000 for a cross-linguistic perspective.)

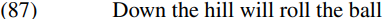

The assumption made is that intransitive clauses have a split vP+VP structure in which the verb raises from V to v provides us with a way of analyzing locative inversion structures such as (87) below, so called because the locative expression down the hill precedes the auxiliary will:

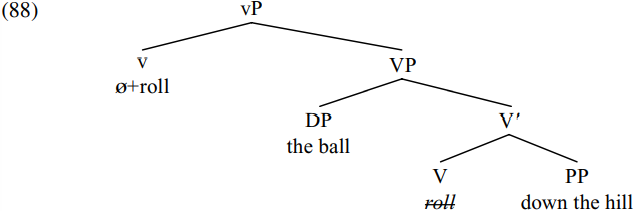

We can derive this as follows. The verb roll merges with its complement down the hill and its specifier the ball to form the VP the ball roll down the hill shown in (39) above. This is then merged with an intransitive light verb which (being strong) triggers movement of the verb roll from V to v, so deriving the structure shown in simplified form below:

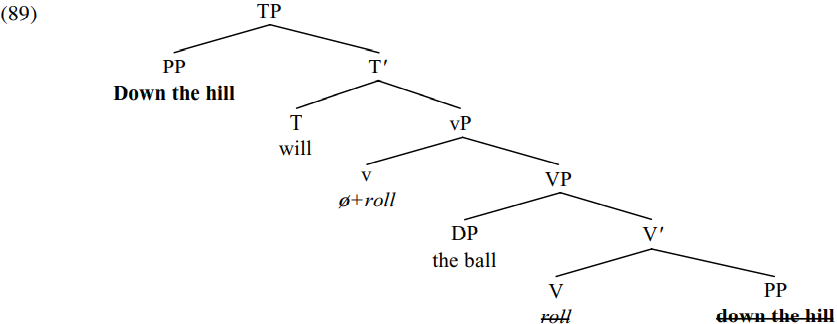

The resulting vP is then merged with a finite T constituent will which has an [EPP] feature. Let’s suppose that T (in addition to its person/number/tense and [EPP] features) in this kind of structure carries some additional feature which enables it to attract the PP down the hill and that as a result, down the hill moves to spec-TP, so deriving the structure:

Such an analysis leaves the subject the ball in situ in spec-VP (hence following the raised verb roll), thereby accounting for the word order we find in (87) Down the hill will roll the ball. Interestingly, a locative inversion structure can occur as the complement of a complementzer like that, as we see from:

This is precisely what would be expected if locative inversion involves movement of a locative to spec-TP, as in (89) above. (See Levin and Rappaport Hovav

1995; Collins 1997; Nakajima 2001; and Bowers 2002 on locative inversion; see Culicover and Levins 2001 for arguments that locative inversion structures are different in nature from structures like ‘Into the room walked carefully the students in the class who had heard about the social psych experiment that we were about to perpetrate’ containing a long italicized postverbal subject.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة