Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 29-3-2022

Date: 2024-06-04

Date: 2024-05-01

|

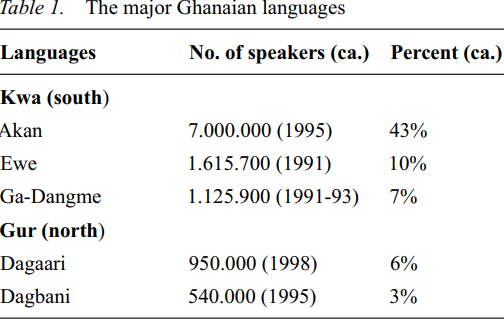

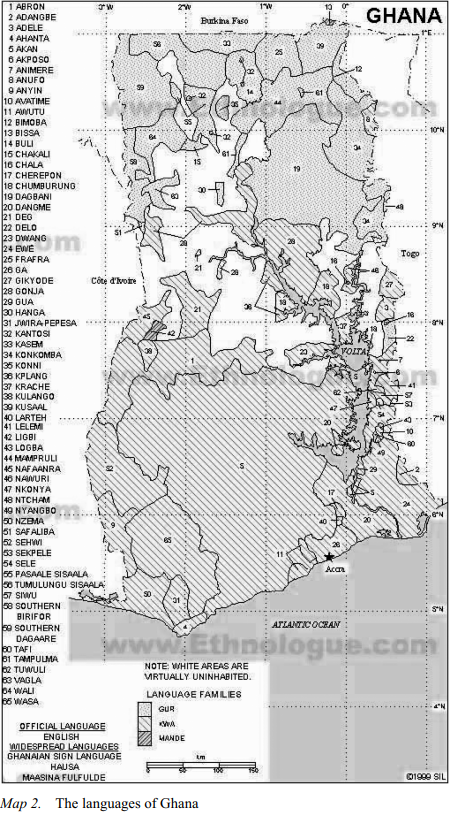

Linguistically, Ghana is highly heterogeneous, with nearly 50 indigenous languages. All of these belong to the Niger-Kordofanian family, in particular two branches of the Central Niger-Congo phylum: Gur languages are spoken in northern Ghana by ca. 24% of the total population, and Kwa languages in the south (ca. 75%). There are also two very small pockets of Mande languages (< 1%). The following table lists the major languages of Ghana and gives a rough estimate of the number and percent of their speakers:

Akan (Twi and Fante) is the biggest Ghanaian language. It is the L1 of about 43% of Ghanaians. The latest census figures (2000, but not yet publicly available) show a strong increase in L2 speakers of Akan, which is now spoken by over 70% of the population and thus the most important lingua franca in the country. This, together with the fact that in colonial times, but also afterwards, the vast majority of teachers came from the south accounts for the strong Kwa influence (Akan, Ewe, Ga-Dangme) in Ghanaian English (GhE).

There is a sociolinguistic north-south divide in Ghana that roughly coincides with the distribution of Gur and Kwa languages. The former are spoken in the rural and generally poorer north, the latter in the more urbanized and richer south. Originally introduced by Nigerian migrants several generations ago, Hausa, a Chadic language of the Afro-Asiatic family, was used along the so-called Hausa Diagonal, the old trade route through Bawku via Tamale, Kintampo or Salaga to Kumasi.

Hausa has thus gained some currency as a lingua franca in parts of Ghana’s north but is still felt to be a foreign language by the majority of Ghanaians. For about a century, unequal economic opportunities have resulted in massive migration to the southern cities, where many northerners settle in so-called Zongos (Hausa for ‘foreigners’ quarters’, poor and often slummy suburbs of towns and cities, inhabited by migrants from northern Ghana and the Sahel, and generally associated with Islam). Hausa was thus transplanted to the south and is today widely used in the southern Zongos, in some major urban markets, and to some extent in the military and the police.

The Bureau of Ghana Languages officially sponsors nine indigenous languages, which thus have ‘national’ status and are used for purposes of public information and education: Akan, Ewe, Dangme, Ga, Nzema, Dagaare, Gonja, Kasem, and Dagbani. Although English is universally called the official language of Ghana, it was never so declared on a constitutional level. The first constitution of Ghana (1957) accepted English as a de facto official language when stipulating that members of parliament had to be proficient in spoken and written English (Article 24). In the latest constitution (1992) one notices a move away from this implicit endorsement of English to a mere acceptance of its expediency. English is no longer mentioned, and indigenous languages, reference to which was conspicuously absent in the 1957 constitution, are now given prominence: Article 39, for example, states that “The State shall foster the development of Ghanaian languages and pride in Ghanaian culture” (even though the latest language policy gives an alibi for non-implementation of these lofty ideals). This reflects the general feeling among Ghanaians that English is a borrowed, foreign language and a residue of colonialism. Because of this, there has been an ongoing debate on the question of the official language since the earliest days of independence. Akan is the most popular but by no means undisputed alternative to English, which has the advantage of ethnic neutrality and of being an important link to the international community.

In spite of the official sanction of indigenous languages, English continues to function as a sociolinguistic High language. It has a prominent place in the national news media, it is used in parliament and public speeches, and it is the language of secondary and tertiary education. However, in none of these domains is it used to the exclusion of indigenous languages, which perform both High and Low functions, particularly in rural and more traditional areas. English, on the other hand, is more deeply rooted on the formal end of the communicative continuum, in more urban and multilingual settings. However, indigenous languages (especially Akan) are currently encroaching on the domains of English. This is shown e.g. by the success of monolingual African FM stations like Peace and Adom (Akan), which seem to be more popular than the predominantly anglophone Joy and Choice.

Since the vast majority of Ghanaians learns English in school, there is as yet no substantial native speaker community, though some middle class children acquire English along with Ghanaian languages or, less frequently, as their sole L1 in the home and English-medium nursery schools and kindergartens. There is also a small group of younger people of the upper-middle-class, the children of the professional elite, often with one foreign parent, who have been raised in homes where only English was spoken and who attended English-medium schools abroad and thus never acquired a Ghanaian language. For the majority of “anglophone” Ghanaians, English, however, coexists with one or more indigenous L1s. The result is a lot of code-switching and borrowing, particularly in the more informal registers of GhE.

Because of Ghana’s colonial past, GhE is oriented towards BrE, but the global influence of AmE in the media has also been noticeable in Ghana in recent years. This has not yet affected the news on TV or the radio, but an American or Americanized accent can be heard in less formal broadcasts like host shows and commercials by big companies such as Guinness (this accent has been given the acronym LAFA ‘locally acquired foreign accent’). A large number of middle-class Ghanaians live in the US and Canada and the accents they acquire while working there are associated with economic success just like the electronic gadgets they bring back on their return. On the other hand, the highly educated Ghanaian who has trained abroad does not acquire this accent – thus none of the senior members of the University of Ghana with PhDs from the US or Canada exhibit this through their accent. This might possibly be associated with an attitude that assumed political significance in the 1950s – that Nkrumah had studied at a Black College in the US and hence the general perception that Busia and Danquah – both British trained – had enjoyed a superior form of education.

|

|

|

|

دراسة تكشف "مفاجأة" غير سارة تتعلق ببدائل السكر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أدوات لا تتركها أبدًا في سيارتك خلال الصيف!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تخفيضات واسعة ودعم مجاني في العمليات الجراحية الكبرى بمستشفى الإمام زين العابدين (ع) التابع للعتبة الحسينية

|

|

|