Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods| Problems for lax-vowel Vowel Shift Rule The divine ~ divinity alternation |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 2025-03-15

Date: 2024-02-27

Date: 2024-05-04

|

According to McCawley (1986), the underlying vowel of [aɪ] ~ [ɪ] in divine ~ divinity is /ǣ/, giving the derivations shown in (3.9).

/ǣ/ will not be adopted here as the underlier for the [aɪ] ~ [ɪ] alternation, for the following reasons:

(1) This would be the only case (excluding profound ~ profundity, in which the underlying vowel never surfaces without a quality change: /ī ē ō/, the underlying vowels of serene, sane and verbose, surface unchanged in these underived forms (but for Diphthongization in some accents), but /ǣ/ in divine must invariably be diphthongized and generally also backed.

(2) Deriving [aɪ] from /ǣ/ commits us to the production of surface diphthongs from underlying monophthongs; but there are good reasons for rejecting this analysis.

The prohibition of underlying diphthongs dates from Chomsky and Halle's assertion (1968: 192) that `contemporary English differs from its sixteenth- or seventeenth-century ancestor in the fact that it no longer admits phonological diphthongs - i.e. sequences of tense low vowels followed by lax high vowels - in its lexical formatives'. This declaration has won widespread acceptance, despite the fact that Chomsky and Halle fail entirely to cite any evidence or justification for it. Indeed, since Modern English, like earlier stages of the language, has surface diphthongs, it is hard to see why the language should have retained this category phonetically, but opted for a phonological restructuring, especially when no alternations are involved, and the learnability of the restructured system must therefore be questioned.

Diphthongization might be favored as enabling a more `elegant' analysis, which remains plausible only if all surface diphthongs are derived from monophthongal sources. It is unfortunate, then, that Diphthongization is not maximally general. For instance, in RP only the long mid monophthongs /ē ō/ are realized consistently as the diphthongs [eɪ], [oʊ]; the high and low vowels /ī ū ɑ̄ ɔ̄/ may surface without offglides. Some American accents have diphthongs in day, go, but not all. In Scots and Scottish Standard English, varieties which we shall explore further, there is no Diphthongization at all, and the long vowels of bee, day, you, go are phonetically monophthongal. In such dialects, a Diphthongization rule could only derive surface [Λi], [Λu] and [ɔi] in divine, profound and boy, and forfeits its claim to be an independently motivated process which is simply extended to these cases.

A final problem for Diphthongization is that, while it has proved relatively easy to derive [aɪ] and [aʊ] from shifted and diphthongized /ī/ and /ū/, finding an appropriate underlier for [ɔɪ] has been more taxing. Various contenders have been proposed, the most notorious being the /œ/ of SPE, whose adoption makes English unique among known languages in having a low front rounded vowel without the corresponding high and mid vowels. The major, and perhaps only, advantage of this choice is that it will regularly undergo Diphthongization to become [œy], thus accounting for the appearance in [ɔy] of a front offglide after a back vowel. However, [ɔɪ] does not figure in alternations (the few apparent examples, such as destroy ~ destruction, are almost certainly allomorphic), and as a remote underlier for non-alternating forms like boy, coin, /œ/ is impermissible in the model proposed here.

Alternative derivations of [ɔɪ] are not markedly more successful. For instance, Zwicky (1974: 59) suggests underlying /Λ̄/; Halle (1977) tentatively proposes deriving [ɔɪ] from /ū/, via Vowel Shift, Diphthongization and a Glide-Switching rule; while Halle and Mohanan (1985) are unable to choose between /ū/ and /ü/. Deriving [ɔɪ] from /ū/ would, as in Halle's account, involve Vowel Shift and Diphthongization to [ɔw], and a further rule fronting the glide; Halle and Mohanan do not, however, propose to unround [w], and the final output will therefore be neither [ɔy] nor [ɔw], but some intermediate amalgamation. If /ü/ is preferred as a source vowel, Vowel Shift, Diphthongization and a rule of Diphthong Backing will produce [ɔy], but Halle and Mohanan (1985: 102) are reluctant to adopt this ostensibly simpler derivation as `it would require a special weakening of the principles that determine the feature complexes in the system of underlying vowels, since the system would now have to include instances of the somewhat marked category of rounded front vowels'.

This is scarcely a convincing objection, given that Halle and Mohanan include in their underlying Modern English vowel system /ɨ Ɨ̄/ and/Λ̄/, three non-surfacing instances of the arguably even more marked category of back unrounded vowels. It is easy to sympathize with Rubach (1984: 35), who observes that `the whole endeavour of deriving /ɔj/ may not be worth the trouble ... one might as well give up the generalization that English has no underlying diphthongs, and so derive boy from //bɔj//'. If /ɔɪ/ is permitted underlyingly, it is a very small step to add /aɪ/ and /aʊ/, which also appear in non-alternating forms like high, bright, fine or loud, round, crowd.

I propose, then, that the underlying vowel system(s) of Modern English should contain at least the diphthongs /ɔɪ/, /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ (centring diphthongs like [ɪə], [ʊə] in RP here, poor will be discussed later). Diphthongization will be replaced by a rule lengthening tense vowels (except in Scots and SSE, where vowel length is governed by the Scottish Vowel Length Rule). The various special rules associated with previous analyses will now be lost: however, V̄SR will produce long tense low front [ǣ] from tensed [ī] in variety and so on, and to convert this into surface [aɪ], one additional rule (3.10) is required. This will be ordered on Level 1 after V̄SR, which will feed it by providing the specification [+low].

The diphthong [aɪ] therefore functions synchronically only as a target in Vowel Shift; no diphthongs shift themselves, although diphthongs were directly involved in the historical Great Vowel Shift. It also follows that the underlying vowel in divine ~ divinity must be the diphthong /aɪ/, the surface vowel in underived divine.

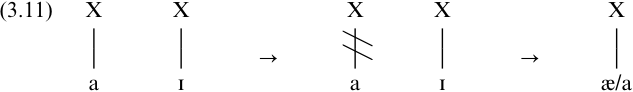

However, since the required surface vowel in divinity is [ɪ], and [ɪ] is derived from a [- back, - round, + low] vowel by V̆SR, such a vowel must result from Trisyllabic Laxing of /aɪ/. Halle and Mohanan (1985) propose that laxing and shortening should be differentiated, but since, at least in RP and GenAm, the only surface vowel-types are short-lax and long-tense, it is preferable to assume that one process implies the other. A laxed vowel will then lose one timing slot: long monophthongs will shorten, while diphthongs will monophthongize, and since [aɪ] is a falling diphthong, it is the less prominent, non-syllabic second element which will be lost (3.11). Further evidence for this analysis of diphthong laxing will be presented below.

|

|

|

|

دراسة تكشف "مفاجأة" غير سارة تتعلق ببدائل السكر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أدوات لا تتركها أبدًا في سيارتك خلال الصيف!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بالصور: زيارة ميدانية لممثل المرجعية العليا والامين العام للعتبة الحسينية لمطار كربلاء الدولي… إشراف مباشر لضمان أعلى معايير التشغيل والجودة

|

|

|