Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 12-3-2022

Date: 2024-04-24

Date: 2024-05-31

|

The Modern English strong verbs which constitute the subject will be defined for present purposes as all those verbs which do not simply add a dental suffix {D} (realized as [-t], [-d] or [-ɪd] depending on the preceding phonological context) to mark the past tense, but also, or instead, change the quality of the stem vowel. This set of strong verbs includes keep ~ kept, sit ~ sat, hold ~ held, fight ~ fought, choose ~ chose, lie ~ lay, draw ~ drew and perhaps 140 others (see Bloch 1947). The term `strong' therefore designates not only historically strong verbs, but also historically weak verbs which now exhibit a vowel mutation in the past tense.

Halle (1977) and Halle and Mohanan (1985) both attempt to derive the past and present tense forms of these strong verbs using common underlying representations and semi-productive phonological rules, despite the fact that these verbs fall into very small sets of related forms, and can only be generated if a number of special rules and extremely remote underliers are adopted. Some of these special ablaut rules (as for swim ~ swam, for instance) will reflect the situation in Proto-Indo-European, where aspect seems to have been regularly expressed by ablaut. However, over the intervening 5,000 years or so, the language has evolved an entirely different tense-marking stratagem in the unmarked case. The derivation of the strong verbs is therefore highly relevant to one question of considerable theoretical importance: that is, is there a principled cut-off point between regular derivation and allomorphy or suppletion? Lass and Anderson (1975: xiii) identify various serious concerns for SGP, and argue that these

seem to cluster around the basic problem of what we might call the `determinacy' of phonological descriptions. To what extent, for instance, does the requirement that all non-suppletive allomorphy be referred to unique morphophonemic representations operated on by `independently motivated' and `phonetically natural' rules still hold? (And, for that matter, how can you tell, in cases less obvious than go: went or good: better, whether you really have suppletion?) This issue seems to be at the bottom of the whole `abstractness' controversy.

The Modern English strong verbs present a classic case of apparent phonological indeterminacy. However, I have argued above that a constrained model of Lexical Phonology will determine what aspects of phonology are derivable; and we shall see that the theory again makes a distinction between a small subclass of strong verbs whose surface alternations are derivable from a single underlier without recourse to special rules, and the great majority where a productive phonological account is ruled out for the present day language.

Let us first briefly review the treatments of the strong verbs in Halle (1977) and Halle and Mohanan (1985); for a much fuller and more detailed critique, see McMahon (1989, ch. 3). Halle (1977) deals with only a limited set of strong verbs (3.43).

Halle argues that all these verb alternations can be captured by means of two allomorphy rules (see (3.44)), but that all the tense stem vowels must subsequently undergo Vowel Shift. Vowel Shift, in other words, obscures the fact that two comparatively simple processes are involved in deriving the past tense forms: past tense forms in (3.43a) become [+low, -high], those in (3.43b) become [+back], and those in (3.43c) undergo both changes.

Halle's analysis assumes that VSR will operate in both the past and the present tense forms of those verbs in (3.43) which have tense stem vowels. This is clearly incompatible with the view of VSR adopted here, where Vowel Shift is limited to cases of tense-lax vowel alternations, with the derived (i.e. tensed or laxed) vowel shifting. Even if we assume that Halle's allomorphy rules create a derived environment by changing some feature of the stem vowel, this will affect only past tense forms. Even if we reformulate the allomorphy rules, perhaps to rewrite the stem, unchanged but for the addition of outer brackets, in the present tense, this will not feed VSR, which requires a purely phonological derived environment, generally supplied by altering the value of [± tense]. Halle's Allomorphy (b) alters the value of the backness feature, which is not mentioned in the structural description of either VSR. Allomorphy (a) affects the height features, [± high] and [± low], which are included in the formulation of VSR; however, this will only allow us to derive the past tense forms of the verbs in (3.43a), since those in (3.43b) and (3.43c) involve the operation of Allomorphy (b), which may not feed VSR. Consequently, only a few forms of a few strong verbs from Halle's list can be handled using a Level 1 VSR, and these do not form a principled class distinct from the others in (3.43): their derivability is accidental.

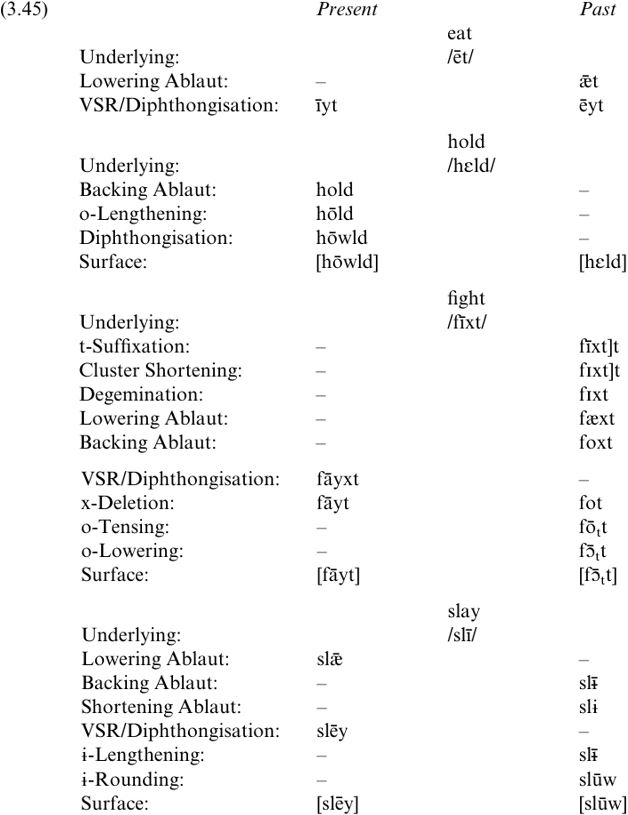

Halle and Mohanan (1985) are rather more ambitious than Halle (1977), and claim to be able to handle all Modern English strong verbs but go, make and stand, the modals, and the auxiliaries be, have and do. They invoke not only VSR and the various tensing and laxing rules, but also ten special rules, each applicable to the stem vowels of a specially marked subset of strong verbs. These include Backing, Lowering and Shortening Ablaut (Halle and Mohanan 1985: rules 30±2), and rules forming and deleting /x/. Some derivations are shown in (3.45). A complete set of strong verb derivations can be found in McMahon (1989); note that Halle and Mohanan (1985) themselves provide no derivations.

Halle and Mohanan order Backing, Lowering and Shortening Ablaut on Level 2, before VSR; they also derive a number of present tense forms like bereave, eat, seek, choose, bind and bear, which are clearly underived, via Vowel Shift. In general, Halle and Mohanan's attitude (1985: 106) is that the rules constitute the core of the phonology, while underliers are adjusted as necessary to fit in with these: `Although any form can be made subject to any rule, provided only that the form satisfy the input conditions of the rule, it is by no means easy to assign to a form a representation such that a set of independently motivated rules will produce the prescribed output.'

As a result, their underlying representations are permitted to differ almost without limit from their surface counterparts: we find /bīx/ for buy ~ bought,/rɪn/ for run ~ ran, /kīm/ for come ~ came,/kεtʃ/ for catch ~ caught and /drɪx/ for draw ~ drew. There are some segments which never surface, like /x/ (which may be inserted by rule or be present underlyingly, as in /bīx/ buy, /fīxt/ fight) and the back unrounded vowels /Λ̄ i ɨ̄ /; and we are faced with the usual problem of `traditional' VSR, in that every verb with a tense stem vowel will have an underlying vowel distinct from surface. `Duke of York' derivations are prevalent, since several verbs with tense stem vowels (including eat ~ ate, choose ~ chose, and forsake ~ forsook) undergo Lowering or Backing Ablaut simply to derive an appropriate input vowel for VSR, which then produces a surface vowel identical to the underlying one. Ablaut rules also apply in present tense forms - Backing Ablaut in fall, hold, run, come, blow and draw, Lowering Ablaut in forsake, slay, catch, say, blow and draw, and Shortening Ablaut in give. I contend that Halle and Mohanan's derivations are unrealistic and untenable, and that any problems their account of the strong verbs causes for the modified Level 1 VSR can surely be discounted.

A final possible argument for phonological generation of the past and present tense forms of strong verbs using Vowel Shift is that children may abstract a VSR on this basis: `the vowel shift pattern ... is of course contained in quite basic vocabulary, notably in the inflectional morph ology of verbs' (Kiparsky and Menn 1977: 65). If the strong verbs are the source of VSR, it is unacceptable to account for these verbs without such a rule. Evidence from Jaeger (1986), however, fails to support this claim. Jaeger's three-year-old informant understood and produced seventy-one strong verbs, but these involved twenty-seven different vowel alternations. Only 20 per cent involved VSR alternations; and these tended to be the least frequently occurring verbs. In short, it seems preferable to regard the strong verbs as learned, with their present and past tense forms lexically stored; VSR will then be irrelevant, and can remain on Level 1.

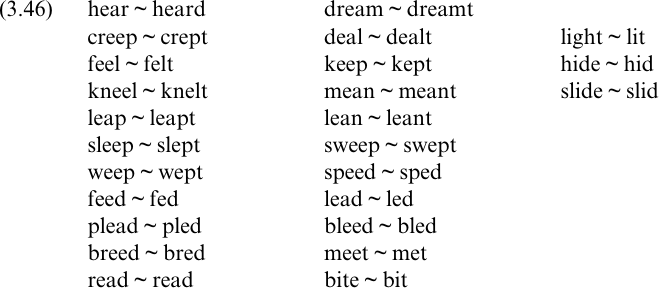

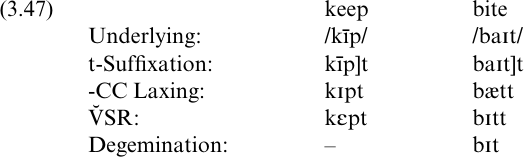

Our conclusion might seem to be that all Modern English strong verbs are irregular, and that all are equally irregular; hence Strang's (1970: 147) contention that `the verbs that do not conform to the ``regular'' pattern of adding-(e)d in past and participle are so divergent that it is hardly worth trying to classify them'. However, Strang continues: `One broad distinction that can be made is between verbs that have two stems, and an alveolar stop terminating the participle (keep, kept, kept), and the rest'; and indeed, it appears that this small subset of `strong' verbs have their past tenses derivable via VSR, with the principles of LP predicting a clear cut-off point between the keep ~ kept class and those whose present and past tense forms are both lexically listed. The derivable strong verbs exhibit an alternation of tense vowel in the present tense and lax vowel in the past, and are listed in (3.46).

It is clear that these verbs exhibit two of the core surface Vowel Shift alternations, namely [ī]~[ε] and [aɪ]~[ɪ]. But can these be derived using a revised, Level 1 VSR?

Kiparsky (1982) suggests that past tense t/d-Suffixation operates twice in the English lexicon. Regular, weak verbs will receive their dental suffix on Level 2. However, a number of verbs, including those listed in (3.46), will be morphologically marked for a special Level 1 word-formation rule attaching the /t/ or /d/ suffix. For most of these Level 1 inflected verbs, the special t/d affixation rule is obligatory, and the later, regular Level 2 rule is blocked due to the EC (Kiparsky 1982); for a small number, however, the earlier rule is speaker-specific, so that the general rule may apply at Level 2 if the Level 1 rule is not selected, giving alternations of past tense forms like Level 1 inflected dreamt [drεmt], leapt [lεpt] or knelt [nεlt] versus regular, weak Level 2 dreamed [drīmd], leaped [līpt] or kneeled [nīld].

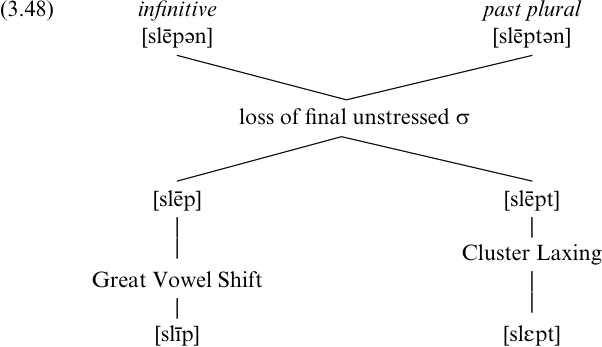

The irregular verbs listed in (3.47) are the only ones which exhibit a surface Vowel Shift alternation, and which can be derived without either additional rules or special marking for VSR. Furthermore, these constitute a class distinct from all truly strong verbs, many of which have exhibited tense-based vowel alternations since Proto-Indo-European. In other cases, ablaut has arisen sporadically during the history of English (as in sell ~ sold, tell ~ told). However, the verbs in (3.47) were still weak as recently as early Middle English, and became `strong' due to the innovation of two Middle English phonological processes, namely Pre-Cluster Shortening and the Great Vowel Shift. The diachronic development of /slip/ ~ /slεpt/ is schematized in (3.48).

As (3.48) shows, early Middle English [slēpən], with past plural [slēptən], became [slēp] and [slεpt] after the loss of final unstressed syllables and the general shortening of vowels before two tautosyllabic consonants. Finally, the Great Vowel Shift affected [slēp], giving [slīp].

It is possible, then, to derive certain `strong' verbs through the regular phonological rules even in a well-constrained model. Modern English sleep ~ slept and so on are synchronically shown to be `strong' by the special morphological marking causing dental suffixation on Level 1, and the derivation involves the synchronic reflexes of the two sound changes which initially created the alternation; although, as we have seen, the present tense form is synchronically underived in phonological terms, with the underlying, lexical and surface forms identical, while the past tense form undergoes laxing and V̌SR. This treatment of the verbs in (3.46) reflects the fact that these became irregular only relatively recently, and that they were propelled out of the weak class in a group, due to the advent of two sound changes. These derivable verbs also constitute the largest subclass of irregular verbs, and arguably preserve the most transparent relationship between present and past forms.

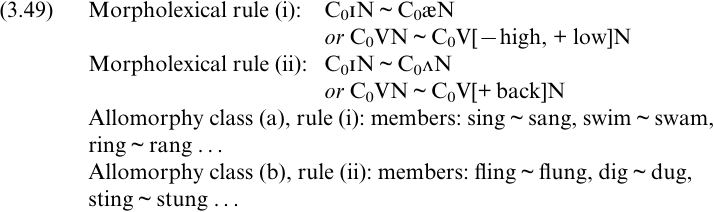

I propose to deal with the remaining strong verbs using allomorphy (although not in the sense of Halle (1977), where allomorphy rules were simply rules of the phonology which applied in a specified set of input forms). There is a good deal of support for this approach. For instance, Halle and Vergnaud (1987: 77) suggest that `the different inflected forms of the English `strong' verbs are determined by rules of the allomorphy component', although this idea is not developed further; while Wiese (1996) proposes that, in German, umlaut is a lexical phonological rule, while the ablaut alternations in strong verbs are unpredictable, unproductive, and therefore allomorphic. Lieber (1982: 30) diagnoses allomorphy in cases where `the relation between stem variants of a morpheme will not be predictable on any phonological or semantic grounds', and indeed uses the Modern English strong verbs as one example.

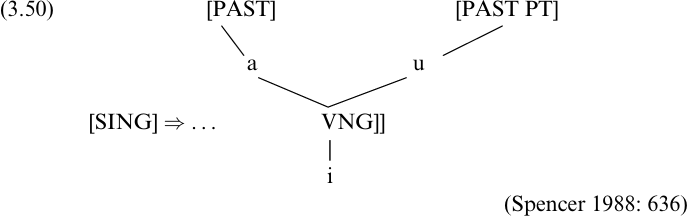

The question then is how we incorporate allomorphy into our grammar. There are various different approaches, although the common factor seems to be the assumption of more than one stored form per verb, with linking of these related entries on phonological, morphological, and/or semantic grounds (Lieber 1982, Spencer 1988, Wiese 1996). For instance, Lieber lists all allomorphs of each morpheme lexically, along with any information peculiar to each allomorph; thus, /profΛnd-/ is bound, while /swæm/ only occurs in the past tense. Semi-regular forms with a common pattern will form an allomorphy class, and members of each class will be linked by morpholexical rules, which have the status of redundancy rules ± an example is given in (3.49).

Anadvantage of this system of stored allomorphs and linking morpho lexical rules is that, presumably, not all speakers need have any rule. Some speakers might learn individual verbs without abstracting any generalizations about specific verb classes; others might recognize similarities between verb pairs and innovate a linking rule.

Alternatively, we might adopt Spencer's (1988) interpretation of allomorphy rules as redundancy statements, which he argues can be seen as blank-filling applications of lexical rules. A morpholexical diacritic will trigger the appropriate structure-building rule, which `constructs the phonological shapes of allomorphs, complete with morphosyntactic feature representation' (Spencer 1988: 625). The representation for a verb like sing ~ sang will then be as shown in (3.50).

For present purposes, it does not particularly matter which approach we adopt to allomorphy in the strong verbs: the important issue is that there is support in the literature for handling these verbs using storage and linking rather than by adopting distant underliers and ill-motivated minor rules. The more interesting aspect of the strong verb story for us is the principled and orderly division which has emerged between verbs like keep ~ kept and bite ~ bit, which were weak until relatively recently and became `strong' due to the operation of two sound changes whose synchronic reflexes are still involved in their derivation, and all the other strong verbs, which are of diverse origins and varying degrees of opacity, and which form only small subclasses at best. This well-motivated division is a direct result of the adoption of the bipartite tense and lax Vowel Shift Rule proposed above, and the anti-abstractness principles which can be imposed on a Lexical Phonology.

In (3.51), I have reduced a number of possible underlying systems for different varieties of Modern English to a single system for illustrative purposes; thus, /ɒ/ is bracketed since it may not appear in GenAm, while /ǣ/and/ɑ̄/ are given as mutually exclusive options; see the discussion of the father vowel. Halle and Mohanan's (1985) vowel system is reproduced in (3.52) for comparison.

The reanalysis of the synchronic VSR proposed above indicates three clear ways in which a constrained Lexical Phonology differs from SGP; these are relevant to the aims and objectives of lexicalist theory.

(1) The strict imposition of constraints inevitably prohibits a maximally simple phonology, if simplicity means a minimal number of rules used maximally; thus, for instance, VSR becomes two rules instead of one, while the majority of lexical rules will apply only on Level 1, and free rides will therefore be eliminated. The evaluation metric will have to change for more concrete phonological models: the optimal phonology will no longer be the one with the most simple and elegant analyses, but the one which most closely adheres to the principles and constraints imposed on it, and which is consistent with both internal and external evidence.

(2) Synchronic phonological rules and the diachronic sound changes which are their source need not be identical, or indeed bear much resemblance to one another. This point has been exemplified by the Great Vowel Shift and its synchronic reflexes, the Vowel Shift Rules, which are formulated differently and have distinct inputs; for instance, the [aʊ]~[Λ] alternation was historically a product of the Great Vowel Shift, but is not included in the synchronic Vowel Shift concept, while [jū]~[Λ] is not historically a Vowel Shift alternation, but is now derivable via the VSR. Concrete lexicalist analyses reveal more enlightening, but less obvious connections between synchrony and diachrony, as shown by the treatment of the Modern English strong verbs, which revealed a principled division between those verbs like keep ~ kept which were most recently transferred from the weak to the strong class, and other verbs which have maintained their ablaut alternations for longer and which are arguably no longer synchronically derivable from a common underlying form.

(3) Different dialects may have different underlying forms for the same lexical items, and different underlying inventories of segments. Illustrations of such differences for varieties of English were given above from the low vowels, where some dialects will have an underlying and surface front vowel in father words, while others will have a back one. Similarly, the rejection of the catch-all Diphthongization rule will mean that different varieties will have different underlying ratios of monophthongs to diphthongs.

I shall return to all of these issues below, exploring in particular the relationship of sound changes and phonological rules, and the idea of underlying dialect differences versus pan-dialectal systems; these have taken second place so far to the development of the constraints of Lexical Phonology, and a comparison of a constrained model with that of Halle and Mohanan (1985). Although Halle and Mohanan restrict their attention to American English (and RP, to a limited extent), we have now reached a stage where we need no longer be restricted by a comparison with earlier models of Lexical Phonology. We can therefore range a little more widely in our consideration of English varieties, and will now introduce Scots and Scottish Standard English which have, as we shall see, certain interesting idiosyncracies in their vowel phonology.

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|