Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-12

Date: 2023-05-04

Date: 2024-06-06

|

Modelling the past

This is not, however, the end of the story. It is all very well to explain the present with reference to the past, but this only pushes the explaining back one step unless we have a clear idea of what happened historically, as well as why: to reverse Labov's (1978) desideratum, we can only hope to understand the present-day situation if and when we feel fully at ease with the past. If we are to account for [r]-Insertion in terms of historical /r/-Deletion, we must understand what the rationale for this change was, and why it happened only in certain varieties of English. As we have seen, some phonologists propose that certain constraints or conditions were innovated in particular dialects, although such accounts are typically incomplete and do not fully explain why the constraints should be dialect-specific. We therefore return to the history of /r/-Deletion.

We saw in Non-rhotic /r/: an insertion analysis An orthoepical interlude above that there is good orthoepical evidence for a gradual weakening of /r/ in all varieties of English, from a trill to a tap, and thence to an approximant. In some rhotic accents, like Scots and SSE, for instance, the stronger tap realization is maintained in onsets, although an approximant is now more common in coda position. This weakening, along with a number of changes affecting vowels before [r], led eventually to the loss of [r] except before vowels in those varieties in which it had weakened fastest and farthest; there are sporadic cases of /r/-loss from the fifteenth century onwards (Lass 1993), but weakening seems to have got under way on a grand scale in the seventeenth century, with wholesale deletion from the early eighteenth century onwards.

In (Non-rhotic /r/: an insertion analysis) I stated the changes leading up to the present-day non-rhotic situation in standard handbook fashion, as the three sequential developments of Pre-/r/ Breaking, Pre-Schwa Laxing, and /r/-Deletion. This sort of statement, whether in terms of segments or of binary features, is not particularly illuminating; and nor is the separate listing of the three developments, which do not seem to have much in common except that the first feeds the second and the third must logically have followed the first. I repeat these changes in (1) for convenience.

(1)

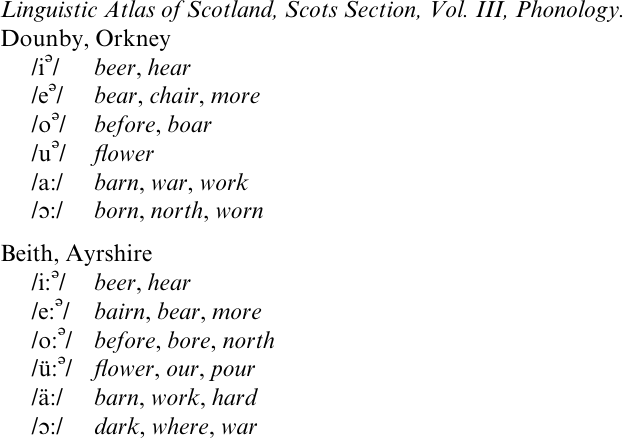

The question is whether we can model the relationship among these changes in a more perspicuous way. Recall that /r/ seems to have been progressively weakening through the Early Modern period in English generally, with the greatest weakening in coda positions, and with certain dialects, which would become non-rhotic, furthest advanced in this weakening. It seems unlikely that we can isolate the social, linguistic and demographic factors which placed certain varieties in the vanguard of the change, although it might be possible to reconstruct some such contributory factors from our knowledge of sound change in progress (Labov 1978). Contemporary evidence reviewed above suggests that Pre-/r/ Breaking took place alongside this weakening; but it need not necessarily have been an independent change, or restricted to those dialects which would become non-rhotic. Even in rhotic varieties like Scots (see (2); from Mather and Speitel 1986), a minimal schwa offglide frequently appears between non-low /i e u o/ and a following /r/; this may also be accompanied by lengthening, since /r/ is a long context for SVLR.

(2)

This partial schwa is rarely perceived by speakers, perhaps because of the acoustic and articulatory similarity of [ə] and approximant [ɹ], to which we shall return below, or the general vowel lengthening which takes place before [r] in any case. Thus, the schwa in rhotic varieties can be ascribed to the realized [r]; in non-rhotic dialects, the present-day absence of [r] means that the resulting centring diphthongs have phonemicized: as Wells (1982: 214) notes, schwa before [r] is `a very natural kind of phonetic development', and `it is perhaps possible to regard it as allophonic in rhotic accents, although in non-rhotic accents (including RP) it is clearly phonemic' (Wells 1982: 216). The increased prominence of schwa in centring diphthongs is therefore clearly bound up with the loss of non-prevocalic [r] in non-rhotic varieties; the question is exactly how this can be modelled.

This line of enquiry may not seem very promising, given the difficulties encountered earlier in discovering any phonological feature unifying /r/ and the relevant vowels. Such insights are certainly not going to be forthcoming in LP as it stands at present, with its old-fashioned and problematic binary feature system, which has been retained as a result of the concentration on organization within the lexicalist model at the expense of work on representation. It may be that we can model these changes, and assess the connections among them, more adequately with a more innovatory feature system, and I propose the gestural framework provided by Articulatory Phonology (Browman and Goldstein 1989, 1991, 1992; McMahon, Foulkes and Tollfree 1994), at least as an interesting possibility. Gestures could be incorporated into even the most restricted version of LP, since their unary nature means they would be subject only to inherent monovalent, rather than radical underspecification.

In Articulatory Phonology, the primitive unit is the gesture, an abstract unit which generates some vocal tract constriction. Underlying representations consist of `scores' of overlapping gestures, which signal contrast and distinctiveness; but these same gestures can, by the application of dynamical equations, be transformed into characterizations of temporally continuous physical movements. The gestural model is very limited, in that no deletion or insertion of gestures is permitted, but has nonetheless been particularly successful in accounting for fast and casual speech processes, and the sound changes to which these give rise. This is achieved by invoking two alterations which gestural scores may undergo: fast speech renditions may differ from canonical forms in the magnitude of gestures, or in the degree of overlap of gestures, and these two modifications are claimed to account for apparent weakenings, insertions, deletions and assimilations.

Let us consider two examples, involving gestural reduction and overlap, and hence weakening and loss of a consonant; a far wider range of possible changes is considered in McMahon, Foulkes and Tollfree (1994) and McMahon and Foulkes (1995).

(3) shows a case of lenition, encoded as reduction in the magnitude of a gesture. Here, a stop becomes a fricative because the closed labial gesture is not fully formed, and the resulting critical labial gesture produces a percept of close approximation. In (4), the speaker in both cases makes the appropriate gesture for the [ktm] cluster, but changes in timing in the fast speech rendition mean that the closed alveolar gesture for [t] is wholly overlapped and hidden by the velar and labial gestures for the adjacent consonants, so that the [t] is not heard. Cross-generationally, these weakenings and deletions may become absolute, so that the fricative, or the form without /t/, may be learned and hence become canonical.

(3)

(4)

In the case of /r/-Deletion, we see both weakening and apparent loss of a segment. In gestural terms, we might regard the progressive lenition as a gradual reduction in the magnitude of the /r/ gestures. Furthermore, these gestures, although still present in the speakers' underlying gestural score, may have been overlapped and hidden an increasing proportion of the time by the gestures appropriate to a following consonant; as we saw in An orthoepical interlude, orthoepical evidence suggests that [r]-loss began pre consonantally, spreading later to pre-pausal position. Occurrence in, or resyllabification into an onset would protect /r/ from the gestural hiding, although not from all the weakening. However, I suggest that the gestures for /r/ were not entirely hidden but rather, in their weakened state, misparsed by hearers and attributed to the pre-existing, partial schwa which preceded /r/; and here, we must make reference to acoustic phonetics. Spectrograms for approximant [ɹ] and [ə] show marked similarities (McMahon 1996), except that F3 for [ɹ] is typically lower. The articulatory strategies speakers use to maintain this low F3 seem to be both variable and vulnerable, in that any relaxation of articulatory effort will allow F3 to raise, increasing its perceptual similarity to schwa. As we have seen (2), even in rhotic varieties a minor schwa offglide on preceding vowels may be part of the characteristic signature of an approximant [H] in any case; this is phonetically very natural, since the tongue will tend to pass through the appropriate articulatory configuration for schwa on its way from most vowels to [ɹ]. It seems that the more the /r/ is weakened, the greater the propensity for hearers to perceive a full schwa vowel in its stead: Jetchev (1993) provides a similar account for apparent vowel insertion changes in Slavic. It is important to note that, in Articulatory Phonology, the stage of gestural hiding is taken to be transitory, and the next generation of speakers will be predicted to learn a form with no underlying /r/, in accord with the rule inversion analysis. This proposal therefore differs critically from Harris's (1994) assumption that floating /r/ can continue to float cross-generationally.

Pre-Schwa Laxing/Shortening would follow, again not as a separate, independently motivated change, but as an automatic consequence, this time phonological. That is, since English has no long diphthongs, with a long first and short second element, the incorporation of schwa into the nucleus would necessitate changes in the pre-existing vowel, which would reduce in length, and concomitantly modify in quality, to give the familiar centring diphthongs. This development is required to maintain the single syllable conformation of words like beer, chair, sure, more. However, although this outline is appropriate for the non-low vowels, /ɑ: ɔ:/ do not always follow the same pattern. Some older speakers of RP, for instance, may maintain schwa after /ɔ:/ in oar, floor and /ɑ:/ in spar, star; but younger RP speakers, and all speakers of many other non-rhotic varieties, lack schwa in these contexts. The weakening /r/ seems to have been perceived after low vowels, not as schwa, but as additional vowel length. Browman and Goldstein (1991: 331) propose that compensatory lengthening does not involve an increase in the duration of vowel gestures: however, part of the vowel gestures are typically hidden by those of an adjacent consonant, and if the consonantal gestures are deleted, those of the vowel are uncovered and perceived as extra length. The question is why this discrepancy of length for low vowels and schwa for the others should have arisen.

A solution might be sought in the gestural composition of /r/ and the vowels concerned, but the gestural analysis of vowels is still too tentative and incomplete to make this a fruitful area for investigation at present (Ladefoged 1990, Foulkes 1993). However, there may be a more straightforward historical answer. As Strang (1970: 112±13) points out, /i: e: u: o:/ were already long at the time of Breaking and /r/-Deletion, while the low vowels were short, and lengthened only as a function of /r/ Deletion. That is, /ar/ and /ɒr/ in card, horse underwent compensatory lengthening to /ɑ: ɔ:/, while the non-low vowels, being already long, could not lengthen further. This may combine with a more general phonetic explanation: the extent of jaw opening for the low vowels, and the fact that [ɾ] and [ɹ] seem crucially to be produced with a non-high tongue body (Francis Nolan, personal communication), may mean that the articulators are less likely to pass through a schwa stage in transit from a low vowel to [ɹ] than when a higher vowel is involved. Interestingly, it is not only the low vowels which lengthen without attracting schwa; this also happens with `the (probably) mixed vowel resulting from the confusion of i, u, and e ... as in first, turn, and earl' (Jespersen 1909: 359). This vowel was historically short, but is now long /з:/, and Jespersen explicitly ascribes this lengthening to the effects of /r/-loss. But /з:/ is not a low vowel, and nor were any of its ancestors /ɪ ε Λ/. We cannot therefore claim that only low vowels before /r/ fail to attract schwa; but again, considering historical vowel length can help, since all the ancestors of /з:/ were short.

We also know that low vowels lengthened in contexts other than before /r/, giving [ɑ:] for many speakers in calm, palm, bath, laugh, grass. We cannot be sure in which dialects this lengthening began, but from its present-day results, we can conclude that it must have been under way relatively promptly in the ancestor of RP, given the underlying distinction which now obtains between /æ/ Sam and /ɑ:/ psalm, as well as between /ɒ/ and /ɔ:/ (see also Harris 1989). We might then speculate that schwa will follow low vowels in those dialects where the low vowels had already lengthened before /r/-Deletion, but that in varieties where /a ɒ/ were still short, /r/-Deletion was accompanied by compensatory lengthening. When the schwa is then lost, as for many younger RP speakers, this can be ascribed to the optional and encroaching operation of smoothing, which applies to all centring diphthongs except /ɪə/ (and even this is affected in some varieties of Australian English ± see Wells 1982). All of this supports our contention that the explanation for the pervasive absence of schwa after low vowels is perhaps partly articulatory, but primarily historical, and based on the length of vowels at the time of /r/-Deletion.

I conclude, then, that short vowels at the time of /r/-loss underwent compensatory lengthening as a function of the disappearance of /r/, while for long vowels, the residual /r/ gestures were perceived as schwa, leading to laxing and shortening of the long preceding vowel to preserve syllable structure. This sort of pattern, with schwa and length in complementary distribution, is not entirely unfamiliar, especially to historical linguists. For instance, Saussure was led to postulate the Proto-Indo-European laryngeals because of the mutually exclusive appearance of unexpected length and unexpected schwa; and again, both testified to the earlier existence of a single, presumably consonantal sound (Lindeman 1987).

Pre-/r/ Breaking, Pre-Schwa Laxing/Shortening and /r/-Deletion now emerge, not as three unrelated developments, but as an integrated complex of changes. We can also account for the apparently a symmetrical behavior of low and non-low vowels in particular non-rhotic dialects. However, we are faced with a final, and potentially even more serious question: if these developments are so natural, and follow so obviously from the weakening of /r/, why did only some English dialects become non-rhotic?

This is, of course, an impossibly big question, relating as it does to the issue, central in much current work on linguistic variation and change (Milroy 1992), of why low-level phonetic processes are only sometimes phonologized, or why only certain variants develop into changes. Nonetheless, we can offer two partial answers. One involves the speed of change: those dialects in which /r/-weakening was farthest advanced seem to be those which progressed to /r/-Deletion, whereas rhotic varieties preserve an earlier stage with less extreme weakening. The question of why weakening began earlier or progressed faster in some dialects than in others may be beyond recovery, given the time depth involved. The second partial explanation relates to general systemic tendencies. If the loss of /r/ is closely connected with the perception of weakened /r/ gestures as schwa, we might rather tangentially seek an account of retention of /r/ in terms of non-perceptibility of schwa. Certain dialects of English seem to have a general tendency towards diphthongization, while others are fundamentally monophthongal, and the former are typically non-rhotic, the latter rhotic. For instance, non-rhotic dialects characteristically have the `true' diphthongs /aɪ aʊ ɔɪ/, the centring diphthongs, and diphthongal reflexes of post-Great Vowel Shift long high-mid /e: o:/. Jespersen (1909: 325) argues that diphthongal [eɪ] was established by around 1750, around the time of the formation of the centring diphthongs, and [oʊ] not much later. On the other hand, Scots, SSE and Hiberno-English lack all but the three `true' diphthongs (and even /aʊ/ is marginal in Scots). Perhaps in dialects where most long vowels are diphthongized, the partial schwa preceding /r/ would have been more

readily perceived as the offglide of a diphthong. Again, of course, we may seem to be pushing the explanation one stage further back: why should some dialects be more prone to diphthongization than others? Aitchison (1989) argues that languages (or dialects) may be caught in a spiral of changes leading in the same direction, giving the effect of a diachronic conspiracy: once a change has taken place, it may provide a template or otherwise channel subsequent changes along a similar route. So a relatively minor change of diphthongization in certain early English dialects may have started the `snowball' that effectively leads to the present-day distribution of [r] in non-rhotic varieties. However, the diphthongization changes must have built up over a considerable period of time, making it rather unlikely that the initial step can be identified: we are then in a sadly common situation for historical linguists, able to see the effects but only hypothesise about the ultimate cause. What is clear, however, is that the synchronic formulation of [r]-Insertion, in terms of the segment involved and the vowels which condition it, becomes completely non-arbitrary from a historical perspective.

|

|

|

|

دراسة تحدد أفضل 4 وجبات صحية.. وأخطرها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|