علم الكيمياء

علم الكيمياء

الكيمياء التحليلية

الكيمياء التحليلية

الكيمياء الحياتية

الكيمياء الحياتية

الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الصناعية |

Read More

Date: 10-8-2016

Date: 16-7-2017

Date: 27-6-2017

|

Pressure

Pressure, p, is force, F, divided by the area, A, on which the force is exerted:

When you stand on ice, you generate a pressure on the ice as a result of the gravitational force acting on your mass and pulling you toward the center of the Earth.

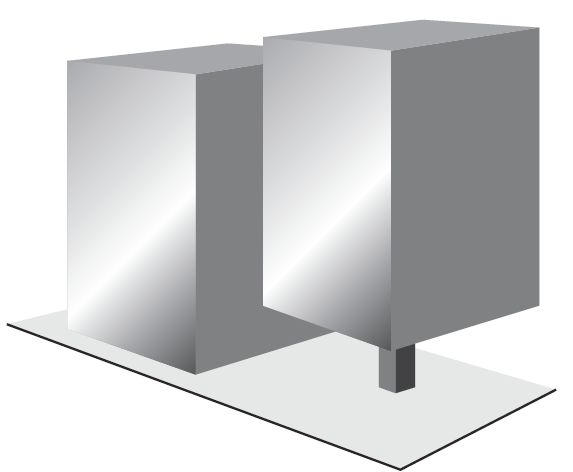

However, the pressure is low because the downward force of your body is spread over the area equal to that of the soles of your shoes. When you stand on skates, the area of the blades in contact with the ice is much smaller, so although your downward force is the same, the pressure you exert is much greater (Fig.1).

Fig. F.1 These two blocks of matter have the same mass. They exert the same force on the surface on which they are standing, but the block on the right exerts a stronger pressure because it exerts the same force over a smaller area than the block on the left.

Pressure can arise in ways other than from the gravitational pull of the Earth on an object. For example, the impact of gas molecules on a surface gives rise to a force and hence to a pressure. If an object is immersed in the gas, it experiences a pressure over its entire surface because molecules collide with it from all directions. In this way, the atmosphere exerts a pressure on all the objects in it. We are incessantly battered by molecules of gas in the atmosphere and experience this battering as the “atmospheric pressure.” The pressure is greatest at sea level because the density of air, and hence the number of colliding molecules, is greatest there.

The atmospheric pressure is very considerable: it is the same as would be exerted by loading 1 kg of lead (or any other material) onto a surface of area 1 cm2. We go through our lives under this heavy burden pressing on every square centimeter of our bodies. Some deep-sea creatures are built to withstand even greater pressures: at 1000 m below sea level the pressure is 100 times greater than at the surface.

Creatures and submarines that operate at these depths must withstand the equivalent of 100 kg of lead loaded onto each square centimeter of their surfaces. The pressure of the air in our lungs helps us withstand the relatively low but still substantial pressures that we experience close to sea level.

When a gas is confined to a cylinder fitted with a movable piston, the position of the piston adjusts until the pressure of the gas inside the cylinder is equal to that exerted by the atmosphere. When the pressures on either side of the piston are the same, we say that the two regions on either side are in mechanical equilibrium. The pressure of the confined gas arises from the impact of the particles: they batter the inside surface of the piston and counter the battering of the molecules in the atmosphere that is pressing on the outside surface of the piston (Fig.2).

Fig. 2 A system is in mechanical equilibrium with its surroundings if it is separated from them by a movable wall and the external pressure is equal to the pressure of the gas in the system.

Provided the piston is weightless (that is, provided we can neglect any gravitational pull on it), the gas is in mechanical equilibrium with the atmosphere whatever the orientation of the piston and cylinder, because the external battering is the same in all directions. The SI unit of pressure is the pascal, Pa:

1 Pa = 1 kg m-1 s-2

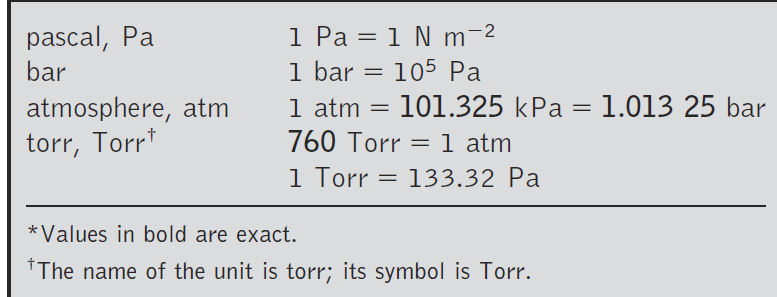

The pressure of the atmosphere at sea level is about 105 Pa (100 kPa). This fact lets us imagine the magnitude of 1 Pa, for we have just seen that 1 kg of lead resting on 1 cm2 on the surface of the Earth exerts about the same pressure as the atmosphere; so 1/105 of that mass, or 0.01 g, will exert about 1 Pa, we see that the pascal is rather a small unit of pressure. Table F.1 lists the other units commonly used to report pressure.1 One of the most important in modern physical chemistry is the bar, where 1 bar = 105 Pa exactly. Normal atmospheric pressure is close to 1 bar.

Table.1 Pressure units and conversion factors*

|

|

|

|

دراسة: حفنة من الجوز يوميا تحميك من سرطان القولون

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تنشيط أول مفاعل ملح منصهر يستعمل الثوريوم في العالم.. سباق "الأرنب والسلحفاة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الطلبة المشاركون: مسابقة فنِّ الخطابة تمثل فرصة للتنافس الإبداعي وتنمية المهارات

|

|

|