تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

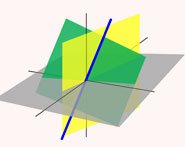

الهندسة

الهندسة

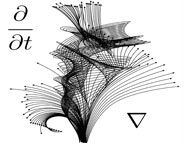

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 30-10-2016

Date: 23-10-2016

Date: 26-10-2016

|

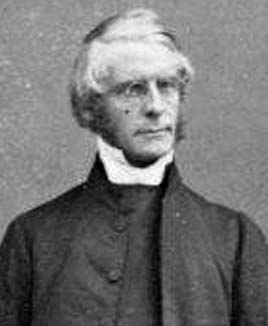

Died: 20 July 1883 in Bishopstowe, Natal, South Africa

John Colenso's father, also named John William Colenso, was a mineral agent associated with tin mining in Cornwall. John was one of four children in the family who were brought up as Nonconformists, that is Protestants outside the Church of England. However, the parents and children all joined the Church of England when John was an adolescent. John attended the mathematical and classical school in St Austell for four years until 1829 when a tin mine that his father had an interest in flooded. This was the first of several tragedies to impact on his life, and the death of his mother at around the same time meant that his family were suddenly in severe difficulties. Because of their financial position, he could not continue his education and took a job as an usher at a Dartmouth school.

The fifteen year old Colenso had two burning ambitions, and he had the necessary determination to achieve them despite the problems. He had a passion for mathematics, and in addition wished to become a priest. His efforts to achieve these aims led him to hard study and, on 22 May 1832, he matriculated at St John's College, Cambridge. Of course he did not have the financial support to see him through his university studies, so he supported himself as a private tutor of mathematics. His talent for mathematics helped too, for he won prizes and scholarships to help with his finances. Academically he was very successful at Cambridge, although hard studies and working to make money left him with no time for a social life. He graduated as Second Wrangler in the Mathematical Tripos of 1836 and, in the same year, was Smith's prizeman. In the following year he was elected to a fellowship at St John's College.

In 1838 Colenso was appointed as a mathematics tutor at Harrow school. He achieved his second ambition when he was ordained in the following year. At this time the school was not in a good financial state and Colenso's salary was low. In order to supplement his income he followed a typical route followed by many schoolmasters at the time of running a boarding house for boys who were studying at the school. However, another tragedy struck when the boarding house was destroyed by fire and, having no insurance, he found himself deeply in debt. He stood no chance of paying off his debt as a mathematics tutor at Harrow so he decided to return to St John's College, Cambridge, and try to make some money through his mathematical talents. During his four years back at St John's he published a number of mathematics books including one on Euclid, one on algebra and one on arithmetic. Although Colenso felt that his books were not particularly good, they proved very popular and Colenso's Arithmetic, in particular, sold widely and brought in a considerable income for its author.

Colenso had met Frances Bunyon, daughter of the head of the London office of the Norwich Union insurance company, while at St John's College. She had an immediate profound affect on Colenso's life for she introduced him to the eminent theologian Frederick Denison Maurice. Frances, part of a circle of free thinking Broad Church people, had first got to know Maurice when she wrote to him thanking him for defending the religious views of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge who she admired. Maurice believed in a united Christian Church that transcended the differences between individuals and races as he had put forward in The Kingdom of Christ (1838). His views, and those of Frances Bunyon and her family, greatly influenced Colenso's thinking. Another important connection came through the fact that Frances was friendly with the wife of the eminent geologist Sir Charles Lyell.

On 8 January 1846 Colenso married Frances Bunyon and, as a consequence, had to resign his Cambridge fellowship. The Bunyon family secured the living of Forncett St Mary in Norfolk for Colenso and he carried out his duties earnestly, having time to continue to use his mathematical talents with private tutoring. In 1853 Colenso was offered the bishopric of Natal in South Africa, a position which fitted perfectly with his missionary interests. He was consecrated on 30 November and immediately sailed to take up his duties in Natal. His aim was to spend a short time there, then return to England so that he could recruit helpers and also raise funds to carry out his vision for the missionary work. Returning to England as planned in 1854, he published Ten Weeks in Natal (1855) setting out his unorthodox ideas.

Colenso returned to Natal with his wife and children, together with a few helpers he had recruited, arriving in May 1855. He set up his headquarters at Bishopstowe, only a few kilometres from Pietermaritzburg. He organised the construction of a cathedral at Pietermaritzburg and two churches at Durban and Richmond within two years of his return. He explained the work in which he was engaged in a letter written on 4 July, 1859 to the Rector of Dunstable [2]:-

My rule is to visit the white population, once a year. But my time is principally occupied with work for the heathen. This is at present, I fancy, the only diocese where the work of preparing grammars, dictionaries, and translations must necessarily fall upon the Bishop. Our work began here with the foundation of the See; and though other Christian bodies - as usual - preceded us into the field, they had done very little indeed towards laying down the language for other teachers, or preparing books for the use of the natives.

In 1861 Colenso published his St Paul's Epistle to the Romans which he subtitled Newly translated and explained from a Missionary Point of View. He wrote in the Preface:-

The teaching of the great Apostle to the Gentiles is here applied to some questions, which daily arise, in Missionary labours among the heathen more directly than usual with those commentators, who have not been engaged personally in such work, but have written from a very different point of view, in the midst of a state of advanced civilization and settled Christianity. Hence they have usually passed by altogether, or only touched very lightly upon, many points, which are of great importance to missionaries, but which seemed to be of no immediate practical interest for themselves or their readers.

In the book he stressed that God loved every race on earth, and that his aim was to defeat sin rather than to punish those who sinned. This view may not appear extreme but contradicted the official position of the Church of England. Also in 1861 he published First Lessons in Science in which he explained Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and Charles Lyell's view that all features of the earth's surface are produced by physical, chemical, and biological processes which act over long periods of geological time. Also in 1861 Colenso published The Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua Critically Examined. He was led to question the literal truth of the Bible when [8]:-

... "a simple-minded, but intelligent, native" asked him if he truly believed the story of Noah and a worldwide flood. Possessing some knowledge of geology from having read the British geologist Charles Lyell, Colenso understood "that a Universal Deluge, such as the Bible manifestly speaks of, could not possibly have taken place in the way described in the Book of Genesis." And he knew that he should not "speak lies in the Name of the Lord." [This led Colenso] to discover "the absolute, palpable, self-contradictions of the narrative." He thus devoted the first of an eventual seven volumes to exposing "the unhistorical character" of that story, often using arithmetical calculations to highlight textual difficulties.

The Anglican church in South Africa charged Colenso with heresy and, after a hearing, he was dismissed from office on 16 December 1863. Colenso had not appeared before the hearing, merely sending them a note to say that it had no authority to dismiss him. He, therefore, ignored the judgement which led to him being excommunicated. However, he took his case to the civil courts and by 1865 he had won his case claiming that only the crown had the authority to dismiss him. The Church in South Africa, angered by the judgement that they did not have complete control over their own affairs, went ahead and appointed a new bishop to take over from Colenso, and this led to a schism in the Anglican Church in Natal.

At this point Colenso had the support of the majority of the white colonists although most English bishops opposed his position. The civil courts awarded him the income and rights over the church buildings and his notoriety brought in crowds whenever he preached. He lost the support of the white colonists with his support of the Zulu, especially after the Anglo-Zulu War broke out in 1879. His final years were difficult ones with almost everyone against him except for his wife who strongly supported him throughout.

The work [5] by Guy gives a fair evaluation of Colenso's contributions. We quote from Gump's review [7]:-

Yet Colenso was no saint, and Guy carefully avoids hagiography. Guy rejects the liberal view that treats Colenso as "a great tribune of African freedom" and "a twentieth-century liberal who somehow wandered into the wrong century". Colenso was a product of his times - he regarded colonialism as a positive good "and saw it as his God-given duty to subordinate the lives of Africans to the demands made by his perception of the world". Appropriately, Africans knew him as the paternalist Sobantu, "the father of the people." Guy also rejects the view from the left which dismisses Colenso as a harbinger of colonialism and imperialism. Instead, he interprets Colenso as a courageous and principled man who was unable to see that injustice was the essence of imperialism. ... [However Guy brings out] Colenso's "struggle against the duplicity, the brutality and the violence of racial oppression"

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|