تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

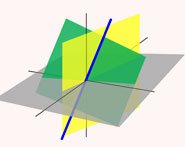

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

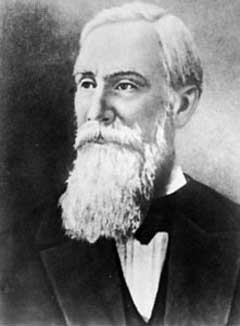

Date: 13-11-2016

Date: 13-11-2016

Date: 13-11-2016

|

Died: 8 December 1894 in St Petersburg, Russia

Pafnuty Chebyshev's parents were Agrafena Ivanova Pozniakova and Lev Pavlovich Chebyshev. Pafnuty was born in Okatovo, a small town in western Russia, south-west of Moscow. At the time of his birth his father had retired from the army, but earlier in his military career Lev Pavlovich had fought as an officer against Napoleon's invading armies. Pafnuty Lvovich was born on the small family estate into a upper class family with an impressive history. Lev Pavlovich and Agrafena Ivanova had nine children some of whom followed in their father's military tradition.

Let us say a little about life in Russia at the time Pafnuty Lvovich was growing up. There was a great deal of national pride in the country following the Russian defeat of Napoleon, and their victory led to Russia being viewed by other European countries with a mixture of fear and respect. On the one hand there was those in the country who viewed Russia as superior to other countries and argued that it should isolate itself from them. On the other hand, educated young Russians who had served in the army had seen Europe, learned to read and speak French and German, knew something of European culture, literature, and science, and they argued for a westernisation of the country.

Pafnuty Lvovich's early education was at home where both his mother and his cousin Avdotia Kvintillianova Soukhareva were his teachers. From his mother he learnt the basic skills of reading and writing, while his cousin acted as a governess to the young boy and taught him French and arithmetic. Later in life Pafnuty Lvovich would greatly benefit from his fluency in French, for it would make France a natural place to visit, French a natural language in which to communicate mathematics on an international stage, and provide a link with the leading European mathematicians. All was not easy for the young boy, however, for with one leg longer than the other he had a limp which prevented him from taking part in many of the normal childhood activities.

In 1832, when Pafnuty Lvovich was eleven years old, the family moved to Moscow. There he continued to be educated at home but he was now tutored in mathematics by P N Pogorelski who was considered the best elementary mathematics tutor in Moscow. Pogorelski was the author of some of the most popular elementary mathematics texts in Russia at the time and certainly inspired his pupil and gave him a solid mathematical education. Chebyshev was, therefore, well prepared for his study of the mathematical sciences when he entered Moscow University in 1837.

The Russian university system that Chebyshev entered had undergone considerable change. Moscow University that he entered had been founded in 1755 and modelled on the German universities. However following the Russian victory over Napoleon there was the westernising movement in the country which we mentioned above. Alexander I, the emperor of Russia, saw the universities as the breeding grounds for what he considered as dangerous doctrines coming from western Europe and the universities were put under pressure in the 1820s to dismiss staff who taught such doctrines. A new minister of education was appointed in 1833 under Nicholas I, who had become Russian emperor in 1825, and he promoted a freer intellectual atmosphere in the universities but on the other hand children of the lower classes were excluded.

At Moscow University the person who was to influence Chebyshev most was Nikolai Dmetrievich Brashman who had been professor of applied mathematics at the university since 1834. Brashman was particularly interested in mechanics but his interests were wide ranging and, in addition to courses on mechanical engineering and hydraulics, he taught his students the theory of integration of algebraic functions and the calculus of probability. Chebyshev always acknowledged the great influence Brashman had been on him while studying at university, and credited him as the main influence in directing his research interests, referring to their "precious personal talks".

The department of physics and mathematics in which Chebyshev studied announced a prize competition for the year 1840-41. Chebyshev submitted a paper on The calculation of roots of equations in which he solved the equation y = f (x) by using a series expansion for the inverse function of f. The paper was not published at the time (although it was published in the 1950s) and it was awarded only second prize in the competition rather than the Gold Medal it almost certainly deserved. Chebyshev graduated with his first degree in 1841 and continued to study for his Master's degree under Brashman's supervision.

Once, much later in his career, Chebyshev objected to being described as a "splendid Russian mathematician" and said that surely he was a "world-wide mathematician" rather than a Russian mathematician. It is very clear that right from the time he began his studies for his Master's degree that Chebyshev aimed at international recognition. His very first paper was written in French and was on multiple integrals. He submitted the paper to Liouville in late 1842 and the paper appeared in Liouville's journal in 1843. It contains a formula which is stated without proof and the following paper in the first part of volume 8 of the journal contains a proof of the formula given by Catalan. In [12] the authors suggest that Chebyshev may have visited Paris in 1842 accompanying the Russian geographer Chikhachev who certainly met Catalan (who assisted Liouville in producing his journal) in December of that year. There is no conclusive evidence, but it must be highly likely that if Chebyshev did not personally visit Paris in 1842 then he sent his paper to Liouville via Chikhachev.

Chebyshev continued to aim at international recognition with his second paper, written again in French, appearing in 1844 published by Crelle in his journal. This paper was on the convergence of Taylor series. In the summer of 1846 Chebyshev was examined on his Master's thesis and in the same year published a paper based on that thesis, again in Crelle's journal. The thesis was on the theory of probability, and in it he developed the main results of the theory in a rigorous but elementary way. In particular the paper he published from his thesis examined Poisson's weak law of large numbers.

During 1843 Chebyshev produced a first draft of a thesis which he intended to submit to obtain his right to lecture once he found a suitable position. Times were hard and Moscow had no suitable positions available for Chebyshev but, in 1847, he was appointed to the University of St Petersburg submitting his thesisOn integration by means of logarithms. In it he generalised methods of Ostrogradski to show that a conjecture which Abel made in 1826 about the integral of f (x)/√R(x), where f (x) and R(x) are polynomials, was true. In a report which he wrote about a visit to Paris in 1852, Chebyshev described how he was asked to develop the ideas further (see for example [11]):-

Liouville and Hermite suggested the idea of developing the ideas on which my thesis had been based. ... in the thesis I considered the case where the differential under the integral contains the square root of a rational function. But it was interesting in several respects to extend those principles to a root of any degree.

Although Chebyshev's thesis was not published until after his death, he published a paper containing some of its results in 1853.

Between arriving in St Petersburg and this 1853 publication Chebyshev published some of his most famous results on number theory. He wrote an important book Teoria sravneny on the theory of congruences which he submitted for his doctorate, defending it on 27 May 1849. This work also received a prize from the Academy of Sciences. He collaborated with Bunyakovsky in producing a complete edition of Euler's 99 number theory papers which they published in two volumes in 1849. Chebyshev's work on prime numbers included the determination of the number of primes not exceeding a given number, published in 1848, and a proof of Bertrand's conjecture.

In 1845 Bertrand conjectured that there was always at least one prime between n and 2n for n > 3. Chebyshev proved Bertrand's conjecture in 1850. Chebyshev also came close to proving the Prime Number Theorem, proving that if

( π(n) log n ) / n

(with π(n) the number of primes ≤ n) had a limit as n → ∞ then that limit is 1. He was unable to prove, however, that

lim ( π(n) log n ) / n as n → ∞

exists. The proof of this result was only completed two years after Chebyshev's death by Hadamard and (independently) de la Vallée Poussin.

Chebyshev was promoted to extraordinary professor at St Petersburg in 1850. Two years later, between July and November 1852, he visited France, London and Germany. We mentioned above his report on that trip during which he had the opportunity to investigate various steam engines and their mechanics in practice. His report covers his studies of applied mechanics as well as his discussions with French mathematicians including Liouville, Bienaymé, Hermite, Serret, Lebesgue, Poncelet, and English mathematicians including Cayley and Sylvester. In Berlin he met Dirichlet:-

It was of great interest for me to become acquainted with the celebrated geometer Lejeune-Dirichlet. ... [I] found an occasion each day to talk with this geometer concerning [applications of calculus to number theory] as well as other questions on pure and applied analysis. ... [I attended] with particular pleasure one of his lectures on theoretical mechanics.

In fact Chebyshev's interest both in the theory of mechanisms and in the theory of approximation stem from his 1852 trip. In [31] Tikhomirov studied Chebyshev's work on approximation theory and writes:-

Chebyshev ... set the foundations of the Russian school of approximation theory: we show the relation of Chebyshev's ideas in approximation theory to applied problems (theory of mechanisms and computational mathematics).

Papers which arose as a direct consequence of the trip included Théorie des mécanismes connus sous le nom de parallélogrammes published in 1854. It was in this work that his famous Chebyshev polynomials appeared for the first time but he later went on to develop a general theory of orthogonal polynomials. In [28] Roy discusses his contributions to on orthogonal polynomials and puts the work into its historical context:-

Chebyshev was probably the first mathematician to recognise the general concept of orthogonal polynomials. A few particular orthogonal polynomials were known before his work. Legendre and Laplace had encountered the Legendre polynomials in their work on celestial mechanics in the late eighteenth century. Laplace had found and studied the Hermite polynomials in the course of his discoveries in probability theory during the early nineteenth century. Other isolated instances of orthogonal polynomials occurring in the work of various mathematicians is mentioned later. It was Chebyshev who saw the possibility of a general theory and its applications. His work arose out of the theory of least squares approximation and probability; he applied his results to interpolation, approximate quadrature and other areas. He discovered the discrete analogue of the Jacobi polynomials but their importance was not recognized until this century. They were rediscovered by Hahn and named after him upon their rediscovery. Geronimus has pointed out that in his first paper on orthogonal polynomials, Chebyshev already had the Christoffel-Darboux formula.

The trip Chebyshev undertook in 1852 was one of many. In addition to the mathematicians we have mentioned that he met on that trip, he also had contacts with other European mathematicians such as Lucas, Borchardt, Kronecker, and Weierstrass (see for example [12]). Almost every summer Chebyshev travelled in Western Europe, but when he did not, he spent the summer in Catherinenthal near Reval (now known as Tallinn in Estonia). We do not have full information about his many Western European visits, but we do know that he spoke at sessions of the French Association for the Advancement of Science between 1873 and 1882, presenting sixteen reports, being at the meetings in Lyon in 1873, Clermont-Ferrand in 1876, Paris in 1878, and La Rochelle in 1882. In addition to his 1852 trip to France, and those just mentioned between 1873 and 1882, we have records of visits he made in 1856, 1864, 1884 and 1893. The 1884 visit, which probably saw him visit a number of European universities, ended at the University of Liège where he led the celebrations to honour Catalan's retirement.

We have mentioned some contributions that Chebyshev made to the theory of probability. In 1867 he published a paper On mean values which used Bienaymé's inequality to give a generalised law of large numbers. As a result of his work on this topic the inequality today is often known as the Bienaymé-Chebyshev inequality. Twenty years later Chebyshev published On two theorems concerning probability which gives the basis for applying the theory of probability to statistical data, generalising the central limit theorem of de Moivre and Laplace. Of this Kolmogorov wrote (see for example [1]):-

The principal meaning of Chebyshev's work is that through it he always aspired to estimate exactly in the form of inequalities absolutely valid under any number of tests the possible deviations from limit regularities. Further, Chebyshev was the first to estimate clearly and make use of such notions as "random quantity" and its "expectation (mean) value".

Let us mention a few further aspects of Chebyshev's work. In the theory of integrals he generalised the beta function and examined integrals of the form

∫ xp (1 - x)q dx.

Other topics to which he contributed were the construction of maps, the calculation of geometric volumes, and the construction of calculating machines in the 1870s. In mechanics he studied problems involved in converting rotary motion into rectilinear motion by mechanical coupling. The Chebyshev parallel motion is three linked bars approximating rectilinear motion. He wrote many papers on his mechanical inventions; Lucas exhibited models and drawings of some of these at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris. In 1893 seven of his mechanical inventions were exhibited at the World's Exposition in Chicago, organised to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' discovery of America, including his invention of a special bicycle for women.

A number of famous mathematicians were taught by Chebyshev and gave a descriptions of him as a lecturer. The first quote we give is by Lyapunov who attended lectures by Chebyshev in the 1870s. The quote is given in a number of places (see for example [1] or [11]):-

His courses were not voluminous, and he did not consider the quantity of knowledge delivered; rather, he aspired to elucidate some of the most important aspects of the problems he spoke on. These were lively, absorbing lectures; curious remarks on the significance and importance of certain problems and scientific methods were always abundant. Sometimes he made a remark in passing, in connection with some concrete case they had considered, but those who attended always kept it in mind. Consequently his lectures were highly stimulating; students received something new and essential at each lecture; he taught broader views and unusual standpoints.

Our second quote concerning Chebyshev as a teacher comes from the writings of Dmitry Grave who attended lectures by Chebyshev in the 1880s (see for example [11]):-

Chebyshev was a wonderful lecturer. His courses were very short. As soon as the bell sounded, he immediately dropped the chalk, and, limping, left the auditorium. On the other hand he was always punctual and not late for classes. Particularly interesting were his digressions when he told us about what he had spoken outside the country or about the response of Hermite or others. Then the whole auditorium strained not to miss a word.

Let us quote from a lecture given by Chebyshev in 1856 where he explained how he saw the interaction of the pure and applied sides of mathematics. It is an interesting quote, for much of Chebyshev's work in mathematics was done following these principles (see for example [1] or [11]):-

The closer mutual approximation of the points of view of theory and practice brings most beneficial results, and it is not exclusively the practical side that gains; under its influence the sciences are developing in that this approximation delivers new objects of study or new aspects in subjects long familiar. In spite of the great advance of the mathematical sciences due to the works of the outstanding mathematicians of the last three centuries, practice clearly reveals their imperfection in many respects; it suggests problems essentially new for science and thus challenges one to seek quite new methods. And if theory gains much when new applications or developments of old methods occur, the gain is still greater when new methods are discovered; and here science finds a reliable guide in practice.

As to Chebyshev's personal life, he never married and lived alone in a large house with ten rooms. He was rich, spending little on everyday comforts but he had one great love, namely that of buying property. It was on this that he spent most of his money but he did financially support a daughter whom he refused to officially acknowledge. He did spend time with this daughter, especially after she married a colonel. Chebyshev often met her and her husband in Rudakovo at the home of his sister Nadiejda.

Chebyshev retired from his professorship at St Petersburg University in 1882; he had been appointed to this particular post 22 years earlier. He had received many honours during his career and a few more were still to come his way. He became a junior academician of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences in 1853 with the chair of applied mathematics, an extraordinary academician in 1856 and an ordinary academician in 1859, again with the chair of applied mathematics. He was elected a Corresponding Member of the Société Royale des Sciences of Liège in 1856, of the Société Philomathique, also in 1856, of the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1871, the Bologna Academy in 1873, the Royal Society of London in 1877, the Italian Royal Academy in 1880, and the Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1893. He was elected a Corresponding Member of the Institut de France in 1860 and a foreign associate of the Institut in 1874. In addition every Russian university elected him to an honorary position, he became an honorary member of the St Petersburg Artillery Academy and the was awarded the French Légion d'Honneur.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دراسة تحدد أفضل 4 وجبات صحية.. وأخطرها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|