تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

The electron

المؤلف:

S. Gibilisco

المصدر:

Physics Demystified

الجزء والصفحة:

p 227

17-9-2020

2709

The electron

An electron has exactly the same charge quantity as a proton but with opposite polarity. Electrons are far less massive than protons, however. It would take about 2,000 electrons to have the same mass as a single proton.

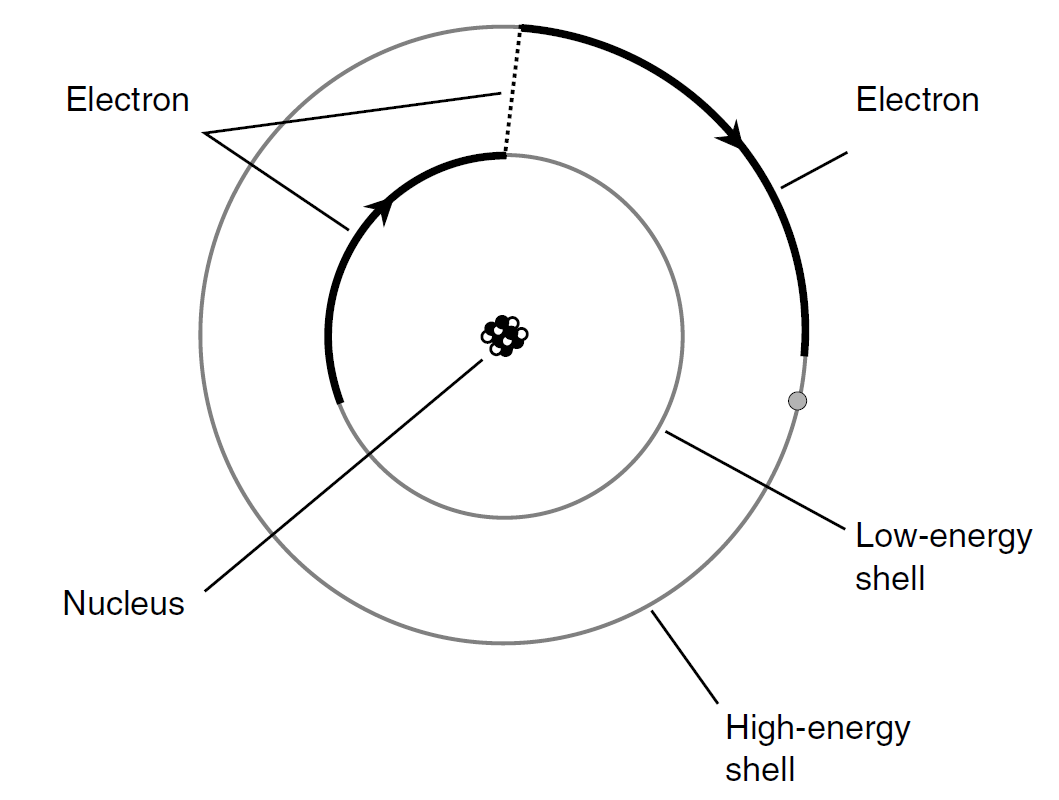

One of the earliest theories concerning the structure of the atom pictured the electrons embedded in the nucleus like raisins in a cake. Later, the electrons were imagined as orbiting the nucleus, making every atom like a miniature star system with the electrons as the planets. Still later, this view was modified further. In today’s model of the atom, the electrons are fast-moving, and they describe patterns so complex that it is impossible to pinpoint any individual particle at any given instant of time. All that can be done is to say that an electron just as likely will be inside a certain sphere as outside. These spheres are known as electron shells. The centers of the shells correspond to the position of the atomic nucleus. The greater a shell’s radius, the more energy the electron has. Figure 1 is a greatly simplified drawing of what happens when an electron gains just enough energy to “jump” from one shell to another shell representing more energy.

Electrons can move rather easily from one atom to another in some materials. These substances are electrical conductors. In other substances, it is difficult to get electrons to move. These are called electrical insulators. In any case, however, it is far easier to move electrons than it is to move protons. Electricity almost always results, in some way, from the motions of electrons in a material.

Generally, the number of electrons in an atom is the same as the number of protons. The negative charges therefore exactly cancel out the positive ones, and the atom is electrically neutral. Under some conditions, however, there can be an excess or shortage of electrons. High levels of radiant energy, extreme heat, or the presence of an electrical field (to be discussed later) can “knock” electrons loose from atoms, upsetting the balance.

Fig. 1. Electrons exist at defined levels, each level corresponding to a specific, fixed energy state.

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الذرية

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الذرية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)