تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء والفلسفة

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Static and dynamic operation

المؤلف:

J. M. D. COEY

المصدر:

Magnetism and Magnetic Materials

الجزء والصفحة:

469

4-3-2021

3530

Static and dynamic operation

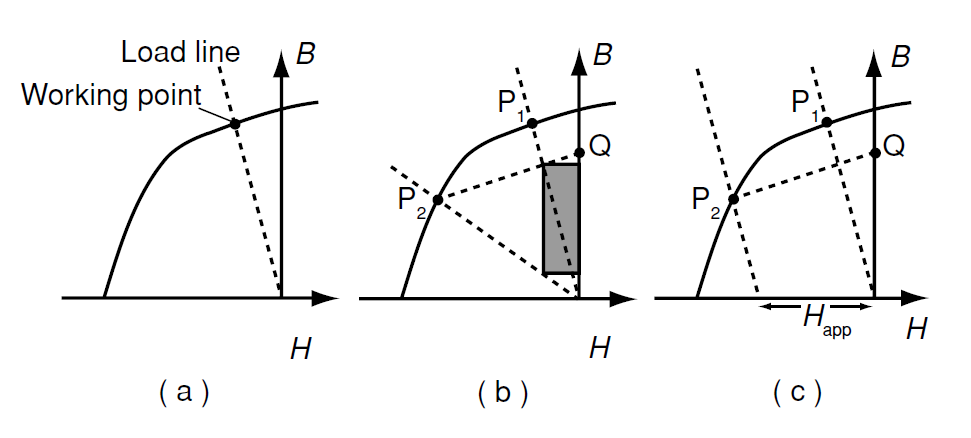

Applications are classified as static or dynamic according to whether the working point in the second quadrant of the hysteresis loop is fixed or moving (Fig. 1). The position of the working point reflects the internal field Hm, which depends in turn on the magnet shape, airgap and any fields that may be generated by electric currents. The working point changes whenever magnets move relative to each other, when the airgap changes or when time-varying currents are present. On account of their square loops, oriented ferrite and rareearth magnets are particularly well suited for dynamic applications that involve changing flux density. Ferrites and bonded metallic magnets also minimize eddy-current losses.

Figure 1: Hysteresis loops showing working points for: (a) a static application, (b) a dynamic application with mechanical recoil and (c) a dynamic application with active recoil.

For mechanical recoil, the airgap changes from a narrow one with reluctance R1 to a wider one with greater reluctance R2. After several cycles, the working point follows a stable trajectory, represented by the line P2Q in Fig. 1(b) whose slope is known as the recoil permeability μR. Recoil permeability is 2–6 μ0 for alnicos, but it is barely greater than μ0 for oriented ferrite and rare-earth magnets. The shaded area in Fig. 1(b) is a measure of the useful recoil energy in the gap, the recoil product (BH)u, which will always be less than (BH)max , but approaches this limit in materials with a broad square loop and a recoil permeability close to μ0.

Active recoil occurs in motors and other devices where the magnets are subject to an H-field during operation as a result of currents in the copper windings. The field is greatest at startup, or in the stalled condition. Active recoil involves displacement of the permeance line along the H-axis.

الاكثر قراءة في المغناطيسية

الاكثر قراءة في المغناطيسية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)