Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Allomorphy

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

120-6

2023-12-19

1946

Allomorphy

As we saw, the same phoneme may be realized in different environments by more than one allophone. Interestingly, a single morpheme may likewise have several allomorphs. A good example is provided by regular plurals in English:

bat+s ‘bats’

dog+s ‘dogs’

place+s ‘places’

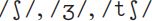

At first sight, this looks like a highly regular pattern of inflection, in which plurals are formed by adding -s to the singular noun. But the orthography disguises the fact that the three endings here are different: /S/ for the first, /Z/ for the second and /IZ/ for the last. The three allomorphs are, furthermore, in complementary distribution: /S/ is used after voiceless consonants (e.g. caps, bets, bricks, coughs), /Z/ after voiced ones (beds, ribs, logs, lathes) and /IZ/ after the sibilants or ‘hissing sounds’ /S/, /Z/,  and

and  (mazes, wishes, matches). We can describe /S/, /Z/ and /IZ/ as three allomorphs of the morpheme <PLURAL>, although we should note here that we are using ‘morpheme’ here in a slightly more abstract sense than hitherto: to avoid terminological confusion where the distinction is important some linguists reserve the term ‘morpheme’ for the abstract representation of a particular grammatical value (e.g. <PLURAL>for the category of ‘number’), and use the term morph (or allomorph) for its actual realization.

(mazes, wishes, matches). We can describe /S/, /Z/ and /IZ/ as three allomorphs of the morpheme <PLURAL>, although we should note here that we are using ‘morpheme’ here in a slightly more abstract sense than hitherto: to avoid terminological confusion where the distinction is important some linguists reserve the term ‘morpheme’ for the abstract representation of a particular grammatical value (e.g. <PLURAL>for the category of ‘number’), and use the term morph (or allomorph) for its actual realization.

More serious problems do, however, beset the morpheme concept in the case of what are termed discontinuous morphemes. Consider the following irregular plurals in English:

mouse – mice

foot – feet

tooth – teeth

man – men

louse – lice

Though this fact is somewhat disguised by the orthography in the case of louse/lice and mouse/mice, all these examples involve monosyllabic items in which a vowel change occurs in the nucleus position in the plural, but the onset and coda are left unchanged. One might therefore wish to posit a discontinuous root morpheme in each case, i.e. /m_s/ for mouse and /f_t/ for foot. Though this might appear to be stretching a point, it is not in fact implausible: in Semitic languages, for example, a number of related words share a common root in which the vowels change, as illustrated by the root k_t_b in Arabic:

Similarly, in German regular past participle forms involve a prefix ge- and a suffix -t (e.g. gelernt, from the verb lernen in ‘Ich habe gelernt’ – ‘I have learned’). But even if one is prepared to extend the morpheme concept to discontinuous elements, a problem remains with our English plurals, namely how are we to analyze <PLURAL> in these words?

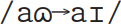

A first, obvious difficulty is that there is no meaningful sense in which these forms can be analyzed as a noun+plural marker sequence: the vowel change which marks plurality is not a suffix. Secondly, whereas with regular plurals a plural morpheme is added (we can include zero plurals here), these plural forms involve a change rather than an addition. One solution might be to describe the <PLURAL> allomorph in mice as a process  , but this seems to bend the original concept of the morpheme as ‘minimal meaning bearing unit’ beyond all recognition without any compensatory gains in terms of descriptive power or elegance. It seems better simply to view these plurals as a non-productive subset of English nouns – in fact a vestige of the umlaut process which survives in German, for example in der Vogel (sg. ‘the bird’) – die Vögel (‘the birds’).

, but this seems to bend the original concept of the morpheme as ‘minimal meaning bearing unit’ beyond all recognition without any compensatory gains in terms of descriptive power or elegance. It seems better simply to view these plurals as a non-productive subset of English nouns – in fact a vestige of the umlaut process which survives in German, for example in der Vogel (sg. ‘the bird’) – die Vögel (‘the birds’).

The morpheme-to-meaning relationship also breaks down in the Celtic languages, where gender agreement is marked by mutation of initial consonants, as in the following examples from Breton:

ar paotr bras ‘the big lad’

an daol vras ‘the big table’

ul levr kozh ‘ an old book’

un gador gozh ‘an old chair’

A mutation known as lenition affects some (but not all) initial consonants of singular feminine nouns after articles (thus taol ‘table’ becomes daol; and kador ‘chair’ becomes gador, but the masculines paotr ‘lad’ and levr ‘book’ are unchanged), and the initial consonant of an adjective qualifying a feminine noun (contrast bras/vras ‘big’, and kozh/gozh ‘old’). Mutation in Breton exemplifies what is known as non-concatenative morphology in that, in contrast to the Turkish examples, nothing is actually added to a stem (calling -aol a ‘stem’ is an unsatisfactory solution because many other Breton words have initial consonants which are unaffected by mutation) and, as was the case for the exponents of <PLURAL> in the forms feet, mice, etc. in English, we cannot identify a morpheme which marks gender.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)