تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Geometrical Optics

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 27

2024-03-16

1550

This is a most useful approximation in the practical design of many optical systems and instruments. Geometrical optics is either very simple or else it is very complicated. By that we mean that we can either study it only superficially, so that we can design instruments roughly, using rules that are so simple that we hardly need deal with them here at all, since they are practically of high school level, or else, if we want to know about the small errors in lenses and similar details, the subject gets so complicated that it is too advanced to discuss here! If one has an actual, detailed problem in lens design, including analysis of aberrations, then he is advised to read about the subject or else simply to trace the rays through the various surfaces (which is what the book tells how to do), using the law of refraction from one side to the other, and to find out where they come out and see if they form a satisfactory image. People have said that this is too tedious, but today, with computing machines, it is the right way to do it. One can set up the problem and make the calculation for one ray after another very easily. So the subject is really ultimately quite simple, and involves no new principles. Furthermore, it turns out that the rules of either elementary or advanced optics are seldom characteristic of other fields, so that there is no special reason to follow the subject very far, with one important exception.

The most advanced and abstract theory of geometrical optics was worked out by Hamilton, and it turns out that this has very important applications in mechanics. It is actually even more important in mechanics than it is in optics.

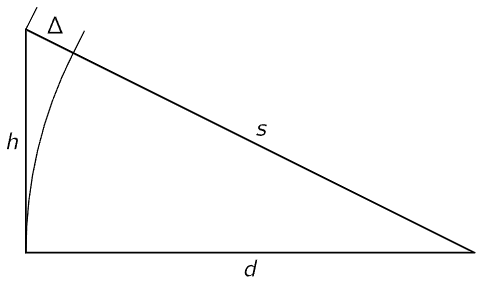

Figure 27–1

In order to go on, we must have one geometrical formula, which is the following: if we have a triangle with a small altitude h and a long base d, then the diagonal s (we are going to need it to find the difference in time between two different routes) is longer than the base (Fig. 27–1). How much longer? The difference Δ=s−d can be found in a number of ways. One way is this. We see that s2−d2=h2, or (s−d)(s+d)=h2. But s−d=Δ, and s+d≈2s. Thus

This is all the geometry we need to discuss the formation of images by curved surfaces!

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)