Compound lenses

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 27

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 27

2024-03-17

2024-03-17

1322

1322

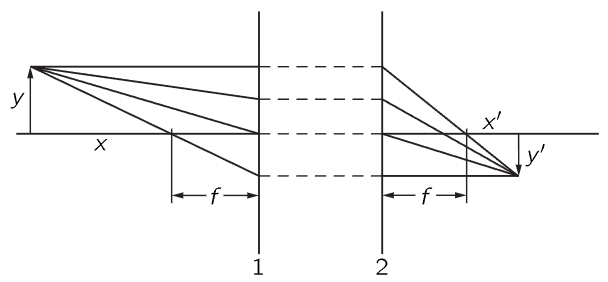

Without actually deriving it, we shall briefly describe the general result when we have a number of lenses. If we have a system of several lenses, how can we possibly analyze it? That is easy. We start with some object and calculate where its image is for the first lens, using formula (27.16) or (27.12) or any other equivalent formula, or by drawing diagrams. So we find an image. Then we treat this image as the source for the next lens, and use the second lens with whatever its focal length is to again find an image. We simply chase the thing through the succession of lenses. That is all there is to it. It involves nothing new in principle, so we shall not go into it. However, there is a very interesting net result of the effects of any sequence of lenses on light that starts and ends up in the same medium, say air. Any optical instrument—a telescope or a microscope with any number of lenses and mirrors—has the following property: There exist two planes, called the principal planes of the system (these planes are often fairly close to the first surface of the first lens and the last surface of the last lens), which have the following properties: (1) If light comes into the system parallel from the first side, it comes out at a certain focus, at a distance from the second principal plane equal to the focal length, just as though the system were a thin lens situated at this plane. (2) If parallel light comes in the other way, it comes to a focus at the same distance f from the first principal plane, again as if a thin lens were situated there. (See Fig. 27–8.)

Fig. 27–8. Illustration of the principal planes of an optical system.

Of course, if we measure the distances x and x′, and y and y′ as before, the formula (27.16) that we have written for the thin lens is absolutely general, provided that we measure the focal length from the principal planes and not from the center of the lens. It so happens that for a thin lens the principal planes are coincident. It is just as though we could take a thin lens, slice it down the middle, and separate it, and not notice that it was separated. Every ray that comes in pops out immediately on the other side of the second plane from the same point as it went into the first plane! The principal planes and the focal length may be found either by experiment or by calculation, and then the whole set of properties of the optical system are described. It is very interesting that the result is not complicated when we are all finished with such a big, complicated optical system.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة