Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Manner adverbials

المؤلف:

GRAHAM KATZ

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P226-C8

2025-04-24

1126

Manner adverbials

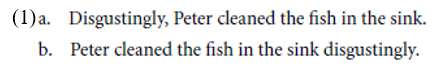

The class of manner adverbs is fairly well defined, both syntactically and semantically. Jackendoff (1972) distinguished manner adverbs as a subclass of the verb phrase adverbs, those that appear sentence-finally but not sentenceinitially. This distinguishes them from modal and speech act adverbs such as possibly or frankly and from temporal and locative adverbials such as yesterday and in Rome. Syntactically, McConnell-Ginet (1982) takes manner adverbs to be not only associated with the VP but to be VP-internal. Clear cases of manner adverbs are such adverbs as quickly, slowly, carefully, violently, loudly, and tightly. Additionally, such prepositional phrases as with all his might and in a careful manner as well as instrumentals such as with a knife can also be taken to be a sort of manner modifier. We should note that many manner adverbs exhibit a limited type of regular polysemy (Jackendoff 1972), having a factive speaker-oriented meaning when sentence-initial and their more standard manner reading sentence-finally. This as illustrated in (1).

Although we will be concerned only with the manner reading here, we will discuss another sort of polysemy below, which may be related.

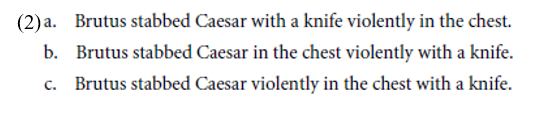

Semantically, manner adverbials are distinguished by a set of entailment properties (Davidson 1967; Parsons 1990). One of these is their scopelessness. As illustrated in (20), the order in which the adverbials appear doesn’t bear on the interpretation of the sentence: (2a), (2b), and (2c) are synonymous.

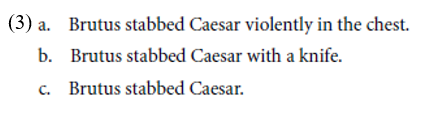

Additionally, manner modifiers have conjunctive interpretations, meaning that they can be dropped from a sentence, preserving its truth. If (2a) is true, so are (3a), (21b), and (3c).

This might seem to indicate that manner adverbial modification is simple intersective predicate modification (if something is a red book, it is red and it is a book). Crucially, however, the truth of (3a) and (3b) does not guarantee the truth of (2a) as would typically be the case for intersective modifiers (if something is red and it is a book, it is a red book). Intuitively, this is because (3a) and (3b) might refer to two different events: a violent stabbing in the chest (that was not done with a knife) and a stabbing with a knife (that was not violent). These three properties – which Landman dubbed “Permutation,”“Drop,” and “Non-Entailment” – characterize true Davidsonian manner modification, and show (as Parsons has argued extensively) that they cannot be treated as simply intersective predicate modification.

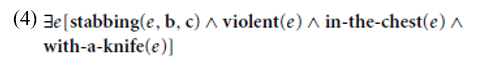

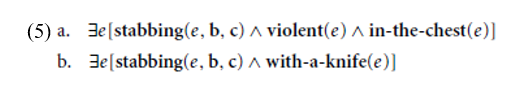

On the Davidsonian account, adverbial modifiers are taken to be event predicates which combine as co-predicates of the verb. How this modification proceeds, whether via a process of event-identification (Higginbotham 2000) or simple functional application (Parsons 1990) will not concern us here. On any Davidsonian account, the logical representation of (2a) is something like the following:

One of the central appeals of Davidsonianism is that elementary facts about first order logic appear to describe exactly the semantic behavior of manner adverbial modifiers analyzed in this way. Given the analysis in (4), it is clear that the order of combination does not matter. Furthermore, since (4) entails both (5a) and (5b) – the analyses of (3a) and (3b) respectively – but is not entailed by them, it is clear why Drop and Non-Entailment hold.

The fact that the properties of Permutation, Drop, and Non-Entailment follow directly from Davidson’s assumption that verbs and manner adverbials are event predicates is certainly strong evidence for the account.

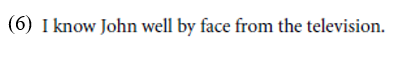

Turning this around, Parsons (1990, 2000), Landman (2000), andMittwoch (2005) have all suggested that if sentences exhibit this trio of Davidsonian properties, then these sentences should be given a Davidsonian analysis. Landman, for example, bases his argument for the Davidsonian analysis of the verb know on what he takes to be the entailments associated with example (6).

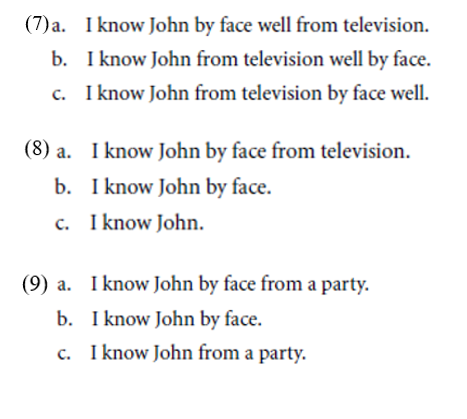

Specifically, Landman claims that (6) entails each of (7a–c) – the “Permutations,” and each of (8a–c) – the “Drops,” and furthermore that the conjunction of (9b) and (9c) does not entail (9a) – the “Non-Entailment.”

If these claims are correct, the argument is a very strong one for providing this state verb (and perhaps state verbs in general) with an underlying Davidsonian state argument. In the following section, we will evaluate these claims.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)