علم الكيمياء

تاريخ الكيمياء والعلماء المشاهير

التحاضير والتجارب الكيميائية

المخاطر والوقاية في الكيمياء

اخرى

مقالات متنوعة في علم الكيمياء

كيمياء عامة

الكيمياء التحليلية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء التحليلية

التحليل النوعي والكمي

التحليل الآلي (الطيفي)

طرق الفصل والتنقية

الكيمياء الحياتية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

الكاربوهيدرات

الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

الانزيمات

الدهون

الاحماض النووية

الفيتامينات والمرافقات الانزيمية

الهرمونات

الكيمياء العضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الهايدروكاربونات

المركبات الوسطية وميكانيكيات التفاعلات العضوية

التشخيص العضوي

تجارب وتفاعلات في الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الحرارية

حركية التفاعلات الكيميائية

الكيمياء الكهربائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الجدول الدوري وخواص العناصر

نظريات التآصر الكيميائي

كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

كيمياء النانو

الكيمياء السريرية

الكيمياء الطبية والدوائية

كيمياء الاغذية والنواتج الطبيعية

الكيمياء الجنائية

الكيمياء الصناعية

البترو كيمياويات

الكيمياء الخضراء

كيمياء البيئة

كيمياء البوليمرات

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الاشعاعية والنووية

An Example of a Polar Reaction: Addition of HBr to Ethylene

المؤلف:

John McMurry

المصدر:

Organic Chemistry

الجزء والصفحة:

9th - p159

6-6-2016

4960

An Example of a Polar Reaction: Addition of HBr to Ethylene

Let’s look at a typical polar process—the addition reaction of an alkene, such as ethylene, with hydrogen bromide. When ethylene is treated with HBr at room temperature, bromoethane is produced. Overall, the reaction can be formulated as

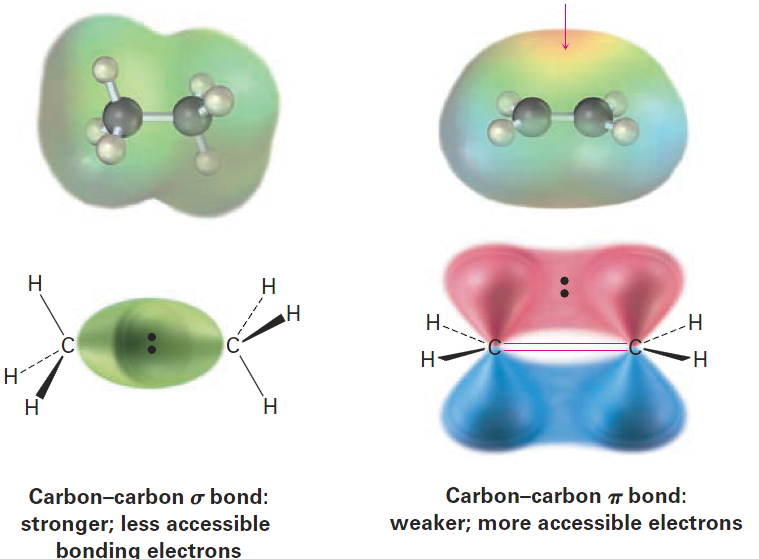

The reaction is an example of a polar reaction type known as an electrophilic addition reaction and can be understood using the general ideas discussed in the previous section. Let’s begin by looking at the two reactants. What do we know about ethylene? The σ part of the double bond results from sp2–sp2 overlap, and the π part results from p–p overlap. What kind of chemical reactivity might we expect from a C=C bond? We know that alkanes, such as ethane, are relatively inert because all valence electrons are tied up in strong, nonpolar, C-C and C-H bonds. Furthermore, the bonding electrons in alkanes are relatively inaccessible to approaching reactants because they are sheltered in s bonds between nuclei. The electronic situation in alkenes is quite different, however. For one thing, double bonds have a greater electron density than single bonds—four electrons in a double bond versus only two in a single bond. In addition, the electrons in the π bond are accessible to approaching reactants because they are located above and below the plane of the double bond rather than being sheltered between the nuclei (Figure 1-1). As a result, the double bond is nucleophilic and the chemistry of alkenes is dominated by reactions with electrophiles.

Figure 1-1 A comparison of carbon–carbon single and double bonds. A double bond is both more accessible to approaching reactants than a single bond and more electron-rich (more nucleophilic). An electrostatic potential map of ethylene indicates that the double bond is the region of highest negative charge.

What about the second reactant, HBr? As a strong acid, HBr is a powerful proton (H+) donor and electrophile. Thus, the reaction between HBr and ethylene is a typical electrophile–nucleophile combination, characteristic of all polar reactions. We’ll see more details about alkene electrophilic addition reactions shortly, but for the present we can imagine the reaction as taking place by the pathway shown in Figure below.

Figure 1-2

The reaction begins when the alkene nucleophile donates a pair of electrons from its C=C bond to HBr to form a new C-H bond plus Br-, as indicated by the path of the curved arrows in the first

step of Figure 1-2. One curved arrow begins at the middle of the double bond (the source of the electron pair) and points to the hydrogen atom in HBr (the atom to which a bond will form). This arrow indicates that a new C-H bond forms using electrons from the former C5C bond. Simultaneously, a second curved arrow begins in the middle of the H-Br bond and points to the Br, indicating that the H-Br bond breaks and the electrons remain with the Br atom, giving Br-.

When one of the alkene carbon atoms bonds to the incoming hydrogen, the other carbon atom, having lost its share of the double-bond electrons, now has only six valence electrons and is left with a positive charge. This positively charged species—a carbon-cation, or carbocation—is itself an electrophile that can accept an electron pair from nucleophilic Br- anion in a second step, forming a C-Br bond and yielding the observed addition product. Once again, a curved arrow in Figure 1-2 shows the electron-pair movement from Br- to the positively charged carbon.

The electrophilic addition of HBr to ethylene is only one example of a polar process; there are many others that we’ll study in depth in later chapters. But regardless of the details of individual reactions, all polar reactions take place between an electron-poor site and an electron-rich site and involve the donation of an electron pair from a nucleophile to an electrophile.