Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-02-06

Date: 25-1-2022

Date: 2024-02-03

|

Types of compounds

In English and other languages there may be a number of different ways of classifying compounds. In order to explain the various types of compounds, there is one indispensable term I need to introduce: the head of the compound. In compounds, the head is the element that serves to determine both the part of speech and the semantic kind denoted by the compound as a whole. For example, in English the base that determines the part of speech of compounds such as greenhouse or sky blue is always the second one; the compound greenhouse is a noun, as house is, and sky blue is an adjective as blue is. Similarly, the second base determines the semantic category of the compound – in the former case a type of building, and in the latter a color. English compounds are therefore said to be right-headed. In other languages, however, for example French and Vietnamese, the head of the compound can be the first or leftmost base. For example a timbre poste (23a) is a kind of stamp, and a nguói ọ̉’ (23c) is a kind of person. French and Vietnamese can therefore be said to have leftheaded compounds.

One common way of dividing up compounds is into root (also known as primary) compounds and synthetic (also known as deverbal) compounds. Synthetic compounds are composed of two lexemes, where the head lexeme is derived from a verb, and the nonhead is interpreted as an argument of that verb. Dog walker, hand washing, and home made are all synthetic compounds. Root compounds, in contrast are made up of two lexemes, which may be nouns, adjectives, or verbs; the second lexeme is typically not derived from a verb. The interpretation of the semantic relationship between the head and the nonhead in root compounds is quite free as long as it’s not the relationship between a verb and its argument. Compounds like windmill, ice cold, hard hat, and red hot are root compounds.

We can also classify compounds more closely according to the semantic and grammatical relationships holding between the elements that make them up. One useful classification is that proposed by Bisetto and Scalise (2005), which recognizes three types of relation. The first type is what might be called an attributive compound. In an attributive compound the nonhead acts as a modifier of the head. So snail mail is (metaphorically) a kind of mail that moves like a snail, and a windmill is a kind of mill that is activated by wind. With attributive compounds the first element might express just about any relationship with the head. For example, a school book is a book used at school, but a yearbook is a record of school activities over a year. And a notebook is a book in which one writes notes. With a new compound (one I’ve just made up) like mud wheel, we are free to come up with any reasonable semantic relationship between the two bases, as long as the first modifies the second in some way: a wheel used in the mud, a wheel made out of mud, a wheel covered in mud, and so on. Some interpretations are more plausible than others, of course, but none of these is ruled out.

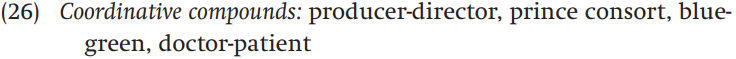

In coordinative compounds, the first element of the compound does not modify the second; instead, the two have equal weight. In English, compounds of this sort can designate something which shares the denotations of both base elements equally, or is a mixture of the two base elements:

A producer-director is equally a producer and a director, a prince consort at the same time a prince and a consort. In the case of blue-green the compound denotes a mixture of the two colors. Finally, there are also coordinative compounds that denote a relation between the two bases (like doctor–patient in doctor–patient confidentiality). We will return to these below. For coordinative compounds we can say that both elements are semantic heads.

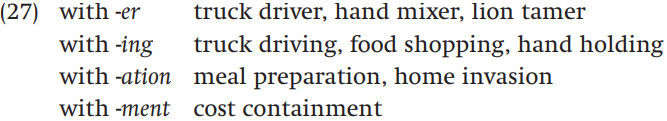

We find a third kind of semantic/grammatical relationship in subordinative compounds. In subordinative compounds one element is interpreted as the argument5 of the other, usually as its object. Typically this happens when one element of the compound either is a verb or is derived from a verb, so the synthetic compounds we looked at above are subordinative compounds in English. Some more examples are given in (27):

It is easy to see that subordinative compounds are interpreted in a very specific way: that is, the first element of the compound is interpreted as the object of the verb that forms the base of the deverbal noun: for example, a truck driver is someone who drives trucks, food preparation involves preparing food, and so on.

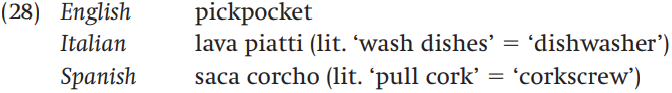

Synthetic compounds are not the only subordinate compounds, however. A second type of subordinate compound is poorly represented in English, but occurs with great frequency in Romance languages like Spanish, French, and Italian:

In these compounds the first element is a verb, and the second bears an argumental relationship to the first element, again typically the complement relationship. We will return to these shortly

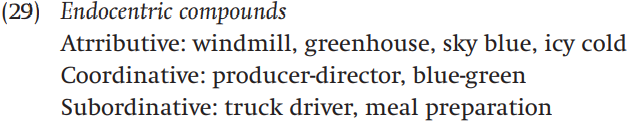

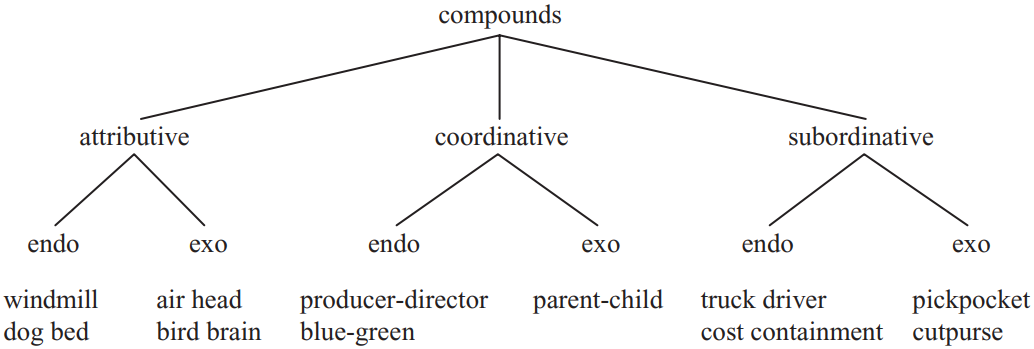

We can further divide attributive, coordinative, and subordinative compounds into endocentric or exocentric varieties. In endocentric compounds, the referent of the compound is always the same as the referent of its head. So a windmill is a kind of mill, and a truck driver is a kind of driver. Endocentric compounds of all three types are illustrated in (29):

The Dutch, French, and Vietnamese compounds in (23) are endocentric, as well, although as we pointed out above, the head occurs on the left in these compounds.

Compounds may be termed exocentric when the referent of the compound as a whole is not the referent of the head. For example, the English attributive compounds in (30) all refer to types of people – specifically stupid or disagreeable people – rather than types of heads, brains, or clowns, respectively. So an air head is a person with nothing but air in her head, and so on. Again, all three types of compounds may be exocentric:

In coordinative compounds like parent-child or doctor-patient the heads refer to types of people, but the compound as a whole denotes a relationship between its elements. We saw examples of exocentric subordinative compounds from English, Spanish, and Italian in (28). English has only a few examples: a pickpocket is not a type of pocket, but a sort of person (who picks pockets). Romance languages have many compounds of this type, however.

The different types of compounds are summarized in Figure 3.3.

|

|

|

|

بـ3 خطوات بسيطة.. كيف تحقق الجسم المثالي؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

دماغك يكشف أسرارك..علماء يتنبأون بمفاجآتك قبل أن تشعر بها!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تواصل إقامة مجالس العزاء بذكرى شهادة الإمام الكاظم (عليه السلام)

|

|

|