Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 24-2-2022

Date: 2023-12-27

Date: 23-4-2022

|

We suggested that schema theory provides a flexible conceptual approach to pragmatic acts. But we have not seen how the kind of interactional issues we have been discussing, might be accommodated. We propose that activity types provide a more holistic approach to the analysis of interaction, and also one that is compatible with schema theory.

The notion of an activity type is usually credited to Stephen Levinson, though similar notions can be seen in earlier research (see Allwood 1976). An activity type, according to Levinson, refers to:

any culturally recognized activity, whether or not that activity is coextensive with a period of speech or indeed whether any talk takes place in it at all ... In particular, I take the notion of an activity type to refer to a fuzzy category whose focal members are goal-defined, socially constituted, bounded events with constraints on participants, setting, and so on, but above all on the kinds of allowable contributions. Paradigm examples would be teaching, a job interview, a jural interrogation, a football game, a task in a workshop, a dinner party, and so on.

(Levinson [1979a] 1992: 69)

He goes on to say that:

Because of the strict constraints on contributions to any particular activity, there are corresponding strong expectations about the functions that any utterances at a certain point in the proceedings can be fulfilling. (ibid.: 79)

This has the important consequence that:

to each and every clearly demarcated activity there is a corresponding set of inferential schemata. (ibid.: 72)

[activity types] help to determine how what one says will be “taken” – that is, what kinds of inferences will be made from what is said. (ibid.: 97)

As can be seen from these quotations, activity types involve both what interactants do in constituting the activity and the corresponding knowledge – schemata – one has of that activity; they have an interactional side and a cognitive side.

Despite indicating that every activity type has a “corresponding set of inferential schemata”, Levinson says nothing more about the cognitive side of activity types. Likewise, subsequent researchers have paid little attention to this dimension (as we saw, Searle just briefly mentions it in connection with explaining how indirect speech acts work). But it is a crucial part of how meanings are generated and understood in interaction. Participants use schematic knowledge in interpreting and managing the particular activity they are engaged in. For example, how are you? is a typical phatic question in many circumstances, but this would be an unlikely interpretation in the context of a doctor-patient consultation. Levinson saw activity types as rescuing the more general inferential framework of the Cooperative Principle (Grice 1975), which could not account for the more particular knowledge-based inferences drawn in particular situations. Inferential schemata are a mechanism for such knowledge-based associative inferencing, as we elaborated.

An important aspect of activity types is that breaks away from traditional approaches to context, which take the view that context is external to the text and relatively stable – it is, in some sense, “out there”. This might be described as the “outside in” approach to context and language; in other words, the analyst looks at how the context shapes the language. But the reverse is also possible. Gumperz’s notion of contextualization cues is based on this idea. He defines them as “those verbal signs that are indexically associated with specific classes of communicative activity types and thus signal the frame of context for the interpretation of constituent messages” (Gumperz 1992: 307; see also Gumperz 1982). This might be described as the “inside out” approach to context and language; in other words, the analyst looks at how language is used to shape the context. Of course, in reality meanings are generated through an interaction between both context and language. Current views in linguistics, of which activity types are a part, emphasize that context is dynamically constructed in situ; both approaches to context are involved.

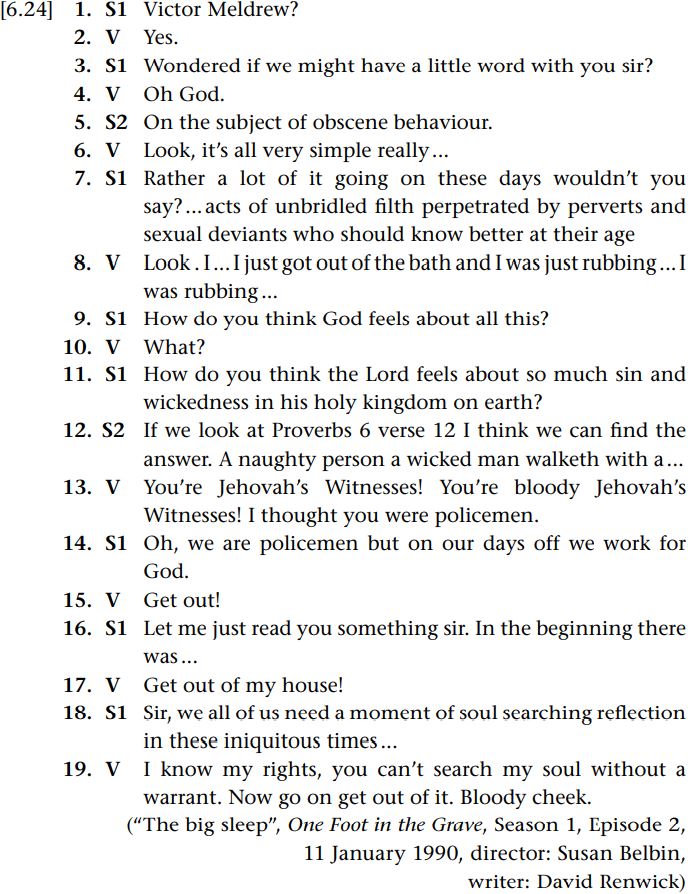

Let us illustrate the points made here. Culpeper and McIntyre (2010) demonstrated how the notion of activity type can capture some of the ways in which script writers exploit dialogue for dramatic effect. We will briefly summarize their analysis of an extract from the BBC award-winning comedy series One Foot in the Grave, specifically the episode “The big sleep” (Series 1, 11/1/90). The plots of this series revolve around Victor Meldrew, a grumpy (though inadvertently humorous) man dealing with the trials and tribulations of being retired. At the beginning of the episode from which our extract is taken, the female window cleaner claims that she is going to report Victor to the police for indecent exposure while she was cleaning the bathroom window (Victor had accidentally exposed himself while grappling with a towel in the bath). Later, Victor has just come in from the garden to be told by his wife that there are two men in the living room waiting to speak to him. Victor goes to speak to them. (V = Victor; S1 = dark suited man; S2 = dark suited man.)

Given that shortly before this scene the audience learns of the threat that Victor will be reported to the police for indecency, it is quite likely that a police-related activity type schema is primed. Research suggests that schemata that have been recently activated are more likely to spring to mind (see the references in Fiske and Taylor 1991: 145–146). Indeed, the activity type constructed here appears to be a police interview. Apart from the fact that the two dark suited individuals readily fill the (plain-clothed) police participant slots of the activity type schema, the opening pragmatic acts (turns 1, 3 and 5) – checking the identity of the interviewee and requesting permission to commence the interview on a particular topic – are strongly associated with the police interview. As for how the pragmatic acts are realized, note that the pragmatic act in turn 3 is indirect, it is literally an assertion concerning the speaker’s wonderings. Such indirectness might be considered, other things being equal, an indication of politeness, as might be the use of the apparently deferential vocative sir. However, politeness on the part of police officers in this activity type is a conventional part of the activity type and cannot be automatically taken to reflect a sincere wish to maintain or enhance social relations with the interactant – it is surface or superficial politeness. Indeed, according to Curl and Drew (2008), the use of “[I was] wondering if” may indicate an orientation to a relatively low entitlement to make the request in the first place rather than to issues of politeness per se. The police officers initiate the conversation, ask the questions and control the topic, all contextual cues of power within the interview activity type. Victor treats S1 and S2 in a manner that suggests that he has conceived of them as police officers. He answers their questions and complies with their requests. Moreover, he adopts a tentative style in accounting for his actions, a style which is apparent in his two instances of the minimizer just, hesitations and two false starts. Victor is playing the appropriate role of interviewee in the police interview activity type.

However, S1’s question How do you think God feels about all this clashes with the police interview activity type. The fact that this clash also registers with Victor is clear from his response: What? While asking questions is perfectly consistent with the police interview activity type, the religious topic is not. This is reinforced by the question How do you think the Lord feels about so much sin and wickedness in his holy kingdom on earth?, and the quotations from the Bible. The idea that this is a police interview activity type can no longer be sustained. The activity type that emerges is one of religious proselytizing, allowing the inference that these are Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religious group that is well-known for making door-to-door visits. In fact, the setting is appropriate to proselytizing, but not a police interview, as police interviews are usually conducted at the police station. This detail was inconsistent with the earlier police interview interpretation, but was probably drowned out by the weight of evidence in the earlier part of the extract pointing towards a police interview. Victor’s linguistic behavior also quickly changes in accord with the new activity type. He abandons the role forced upon him as a result of the power dynamics of the police interview activity type. He uses commands, makes statements about what the two Jehovah’s Witnesses are and are not allowed to do, and evaluates the situation using semi-taboo language. Note that the activity types we see in this abstract, the police interview and the proselytising activity types, share some linguistic and contextual characteristics but differ in others. The focal point of obscene behavior is common to both, as are speech acts of questioning and asserting. As for the differences, the religious aspects are only relevant to proselytising; the initial identity check and the superficial politeness are only relevant to the police interview; the power relationships are diametrically opposite in the two activity types; and so on.

Interestingly, the writer resolves the potential conflict in S1 and S2 being Jehovah’s Witnesses and yet at the beginning of the extract sounding like police officers by providing the information that they are indeed police officers, but off duty. This, then, explains the “leakage” from the police interview activity type into the proselytising activity type. In the final turn of the extract, Victor demonstrates that he is now conscious of the cause of his confusion by blending linguistic elements of the two activity types. His assertion that you can’t search my soul without a warrant would be an appropriate turn of phrase for police discourse were it not for the word soul, which is incongruous and seems more appropriate to religious proselytising. Victor appears to blend aspects of the two activity types together, a neat comedic finale to the scene.

|

|

|

|

لشعر لامع وكثيف وصحي.. وصفة تكشف "سرا آسيويا" قديما

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

كيفية الحفاظ على فرامل السيارة لضمان الأمان المثالي

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم التربية والتعليم يطلق الامتحانات النهائية لمتعلِّمات مجموعة العميد التربوية للبنات

|

|

|