Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 16-2-2022

Date: 2023-11-11

Date: 2023-10-14

|

Having looked at evidence that CP can be split into a number of different projections, we now turn to look at evidence arguing that VPs should be split into two distinct projections – an outer VP shell and an inner VP core. For obvious reasons, this has become known as the VP shell analysis.

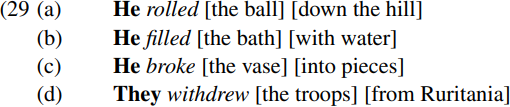

The sentences we have analyzed so far have generally contained simple verb phrases headed by a verb with a single complement. Such single-complement structures can easily be accommodated within the binary-branching framework adopted here, since all we need say is that a verb merges with its complement to form a (binary-branching) V-bar constituent. However, a particular problem for the binary-branching framework is posed by three-place predicates like those italicized in (29) below which have a (bold-printed) subject and two (bracketed) complements:

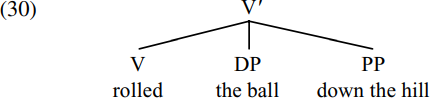

If we assume that complements are sisters to heads, it might seem as if the V-bar constituent headed by rolled in (29a) has the structure (30) below:

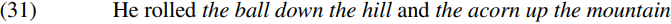

However, a structure such as (30) is problematic within the framework adopted here. After all, it is a ternary-branching structure (V-bar branches into the three separate constituents, namely the V rolled, the DP the ball and the PP down the hill), and this poses an obvious problem within a framework which assumes that the merger operation which forms phrases is an inherently binary operation which can only combine constituents in a pairwise fashion. Moreover, a ternary-branching structure such as (30) would wrongly predict that the string the ball down the hill does not form a constituent, and so cannot be coordinated with another similar string (given the traditional assumption that only identical constituents can be conjoined) – yet this prediction is falsified by sentences such as:

How can we overcome these problems?

One answer is to suppose that transitive structures like He rolled the ball down the hill have a complex internal structure which is parallel in some respects to causative structures like He made the ball roll down the hill (where MAKE has roughly the same meaning as CAUSE). On this view the ball roll down the hill would serve as a VP complement of a null causative verb (which can be thought of informally as an invisible counterpart of MAKE). We can further suppose that the null causative verb is affixal in nature and so triggers raising of the verb roll to adjoin to the causative verb, deriving a structure loosely paraphraseable as He made + roll [the ball roll down the hill], where roll is a trace copy of the moved verb roll. We could then say that the string the ball down the hill in (31) is a VP remnant headed by a trace copy of the moved verb roll. Since this string is a VP constituent, we correctly predict that it can be coordinated with another VP remnant like the acorn up the mountain – as is indeed the case in (31).

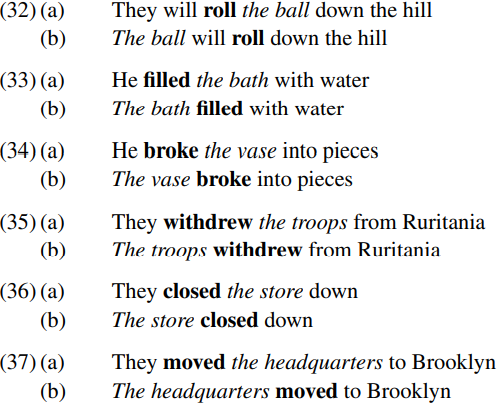

Analyzing structures like roll the ball down the hill as transitive counterparts of intransitive structures is by no means implausible, since many three-place transitive predicates like roll can also be used as two-place intransitive predicates in which the (italicized) DP which immediately follows the (bold-printed) verb in the three-place structure functions as the subject in the two-place structure – as we see from sentence-pairs such as the following:

(Verbs which allow this dual use as either three-place or two-place predicates are sometimes referred to as ergative predicates.) Moreover, the italicized DP seems to play the same thematic role with respect to the bold-printed verb in each pair of examples: for example, the ball is the THEME argument of roll (i.e. the entity which undergoes a rolling motion) both in (32a) They will roll the ball down the hill and in (32b) The ball will roll down the hill. Evidence that the ball plays the same semantic role in both sentences comes from the fact that the italicized argument is subject to the same pragmatic restrictions on the choice of expression which can fulfil the relevant argument function in each type of sentence: cf.

If principles of UG correlate thematic structure with syntactic structure in a uniform fashion (in accordance with Baker’s 1988 Uniform Theta Assignment Hypothesis/UTAH), then it follows that two arguments which fulfil the same thematic function with respect to a given predicate must be merged in the same position in the syntax.

An analysis within the spirit of UTAH would be to assume that since the ball is clearly the subject of roll in (32a) The ball will roll down the hill, then it must also be the case that the ball originates as the subject of roll in (32b) They will roll the ball down the hill. But if this is so, how come the ball is positioned after the verb roll in (32b), when subjects are normally positioned before their verbs? A plausible answer to this question within the framework we are adopting here is to suppose that the verb roll moves from its initial (post-subject) position after the ball into a higher verb position to the left of the ball. More specifically, adapting ideas put forward by Larson (1988, 1990), Hale and Keyser (1991, 1993,1994) and Chomsky (1995), let’s suppose that the (b) examples in sentences like (32)–(37) are simple VPs, but that the (a) examples are split VP structures which comprise an outer shell and an inner core.

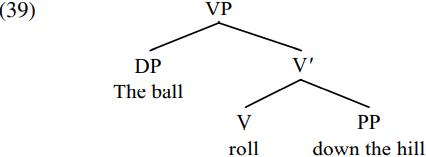

More concretely, let’s make the following assumptions. In (32b) The ball will roll down the hill, the V roll is merged with its PP complement down the hill to form the V-bar roll down the hill, and this is then merged with the DP the ball to form the VP structure (39) below:

In the case of (32b), the resulting VP will then be merged with the T constituent will to form the T-bar will roll down the hill; the [EPP] and  -features of [T will] trigger raising of the subject the ball into spec-TP to become subject of will (in the manner shown by the dotted arrow below), deriving:

-features of [T will] trigger raising of the subject the ball into spec-TP to become subject of will (in the manner shown by the dotted arrow below), deriving:

The resulting TP is subsequently merged with a null declarative C constituent. (we simplify exposition by omitting details like this which are not directly relevant to the point at hand.)

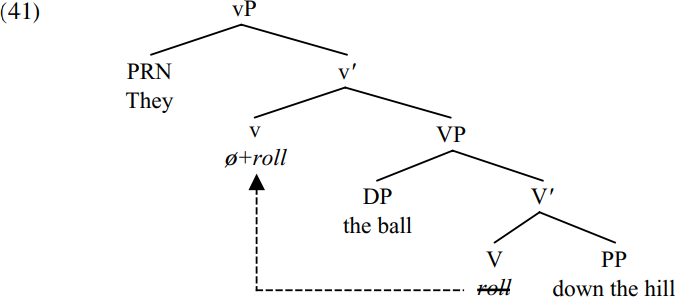

Now consider how we derive (32a) They will roll the ball down the hill. Let’s suppose that the derivation proceeds as before, until we reach the stage where the VP structure (39) the ball roll down the hill has been formed. But this time, let’s assume that the VP in (39) is then merged as the complement of an abstract causative light verb (v) – i.e. a null verb with much the same causative interpretation as the verb MAKE (so that They will roll the ball down the hill has a similar interpretation to They will make the ball roll down the hill). Let’s also suppose that this causative light verb is affixal in nature (or has a strong V-feature), and that the verb roll adjoins to it, forming a structure which can be paraphrased literally as ‘make+roll the ball down the hill’–a structure which has an overt counterpart in French structures like faire rouler la balle en bas de la colline (literally ‘make roll the ball into bottom of the hill’). The resulting v-bar structure is then merged with the subject they (which is assigned the  -role of AGENT argument of the causative light verb), to form the complex vP (41) below (lower-case letters being used to denote the light verb, and the dotted arrow showing movement of the verb roll to adjoin to the null light verb ø):

-role of AGENT argument of the causative light verb), to form the complex vP (41) below (lower-case letters being used to denote the light verb, and the dotted arrow showing movement of the verb roll to adjoin to the null light verb ø):

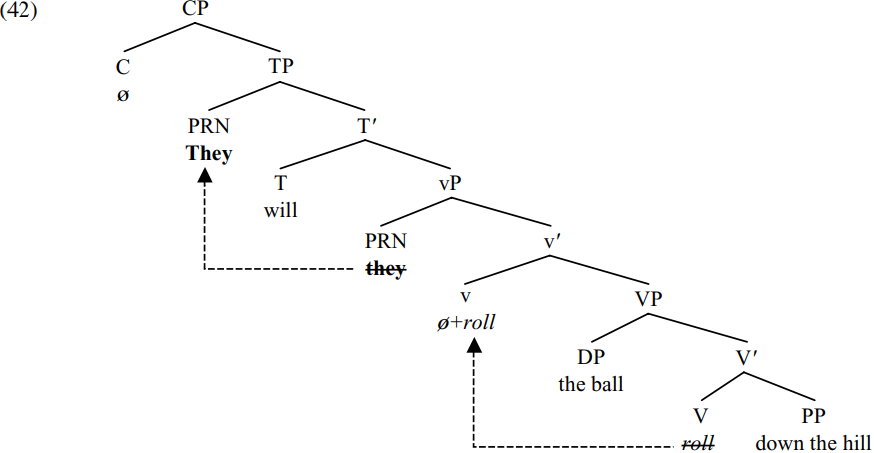

Subsequently, the vP in (41) merges with the T constituent will, the subject they raises into spec-TP, and the resulting TP is merged with a null declarative complementizer, forming the structure (42) below (where the dotted arrows show movements which have taken place in the course of the derivation):

The analysis in (42) correctly specifies the word order in (32a) They will roll the ball down the hill. (See Stroik 2001 for arguments that do is used to support a null light verb in elliptical structures such as John will roll a ball down the hill and Paul will do so as well.)

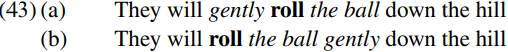

The VP-shell analysis in (42) provides an interesting account of an otherwise puzzling aspect of the syntax of sentences like (32a) – namely the fact that adverbs like gently can be positioned either before roll or after the ball, as we see from:

Let’s suppose that adverbs like gently are adjuncts, and that adjunction is a different kind of operation from merger. Merger extends a constituent into a larger type of projection, so that (e.g.) merging T with an appropriate complement extends T into T-bar, and merging T-bar with an appropriate specifier extends T-bar into TP. By contrast, adjunction extends a constituent into a larger projection of the same type, e.g. merging a moved V with a minimal projection like T forms a larger T constituent; merging an adjunct with an intermediate projection like T-bar extends T-bar into another T-bar constituent; merging an adjunct with a maximal projection like TP forms an even larger TP – and so on. (See Stepanov 2001 and Chomsky 2001 for technical accounts of differences between adjunction and merger.) Let’s suppose that gently is the kind of adverb which can adjoin to an intermediate verbal projection. Given this assumption and the light-verb analysis in (42), we can then propose the following derivations for (43a,b).

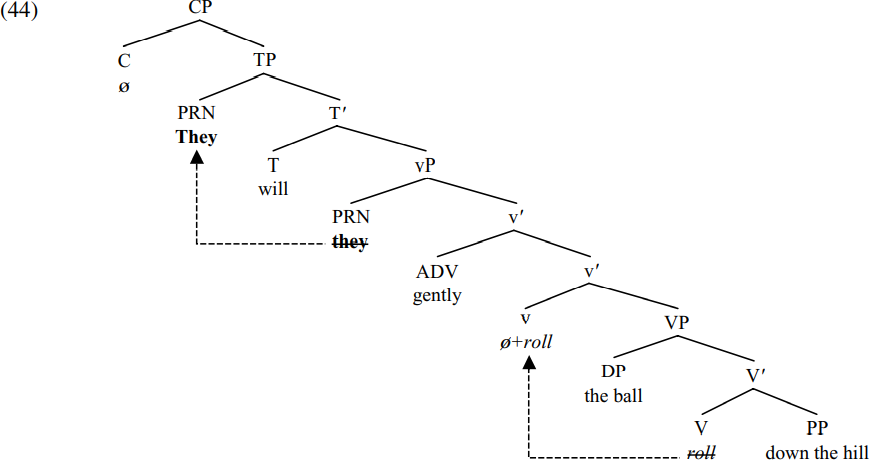

In (43a), the verb roll merges with the PP down the hill to form the V-bar roll down the hill, and this V-bar in turn merges with the DP the ball to form the VP the ball roll down the hill, with the structure shown in (39) above. This VP then merges with a null causative light verb ø to which the verb roll adjoins, forming the v-bar ø+roll the ball roll down the hill. The resulting v-bar merges with the adverb gently to form the larger v-bar gently ø+roll the ball roll down the hill; and this v-bar in turn merges with the subject they to form the vP they gently ø+roll the ball roll down the hill. The vP thereby formed merges with the T constituent will, forming the T-bar will they gently ø+roll the ball roll down the hill. The subject they raises to spec-TP forming the TP they will they gently ø+roll the ball roll down the hill. The resulting TP is then merged with a null declarative complementizer to derive the structure shown in simplified form in (44) below (with arrows showing movements which have taken place):

The analysis in (44) correctly specifies the word order in (43a) They will gently roll the ball down the hill.

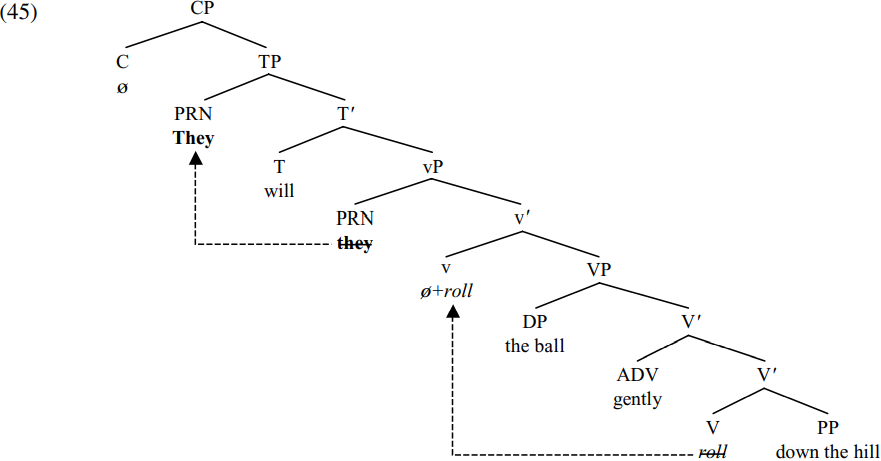

Now consider how (43b) They will roll the ball gently down the hill is derived. As before, the verb roll merges with the PP down the hill, forming the V-bar roll down the hill. The adverb gently then merges with this V-bar to form the larger V-bar gently roll down the hill. This V-bar in turn merges with the DP the ball to form the VP the ball gently roll down the hill. The resulting VP is merged with a causative light verb [v ø] to which the verb roll adjoins, so forming the v-bar ø+roll the ball gently roll down the hill. This v-bar is then merged with the subject they to form the vP they ø+roll the ball gently roll down the hill. The vP thereby formed merges with [T will], forming the T-bar will they ø+roll the ball gently roll down the hill. The subject they raises to spec-TP, and the resulting TP is merged with a null declarative C to form the CP (45) below (with arrows showing movements which have taken place):

The different positions occupied by the adverb gently in (44) and (45) reflect a subtle meaning difference between (43a) and (43b): (43a) means that the action which initiated the rolling motion was gentle, whereas (43b) means that the rolling motion itself was gentle.

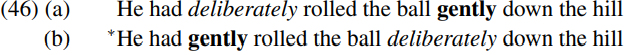

A light-verb analysis also offers us an interesting account of adverb position in sentences like:

Let’s suppose that deliberately (by virtue of its meaning) can only be an adjunct to a projection of an agentive verb (i.e. a verb whose subject has the thematic role of AGENT). If we suppose (as earlier) that the light verb [v ø] is a causative verb with an AGENT subject, the contrast in (46) can be accounted for straightforwardly: in (46a) deliberately is contained within a vP headed by a null agentive causative light verb; but in (46b) it is contained within a VP headed by the non-agentive verb roll. (The verb roll is a non-agentive predicate because its subject has the  -role THEME, not AGENT.) We can then say that adverbs like deliberately are adverbs which adjoin to a v-bar headed by an agentive light verb, but not to V-bar.

-role THEME, not AGENT.) We can then say that adverbs like deliberately are adverbs which adjoin to a v-bar headed by an agentive light verb, but not to V-bar.

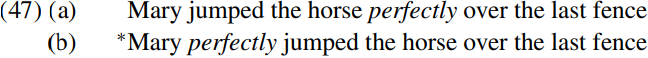

This in turn might lead us to expect to find a corresponding class of adverbs which can adjoin to V-bar but not v-bar. In this connection, consider the following contrasts (adapted from Bowers 1993, p. 609):

Given the assumptions made here, the derivation of (47a) would be parallel to that in (45), while the derivation of (47b) would be parallel to that in (44). If we assume that the adverb perfectly (in the relevant use) can function only as an adjunct to a V-projection, the contrast between (47a) and (47b) can be accounted for straightforwardly: in (47a), perfectly is adjoined to a V-bar, whereas in (47b) it is merged with a v-bar (in violation of the requirement that it can only adjoin to a V-projection).

As we have seen, the VP shell analysis outlined here provides an interesting solution to the problems posed by three-place predicates which have two complements. However, the problems posed by verbs which take two complements arise not only with transitive verbs which have intransitive counterparts (like those in (32)–(37) above), but also with verbs such as those bold-printed in (48) below (the complements of the verbs being bracketed):

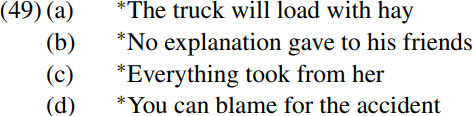

Verbs like those in (48) cannot be used intransitively, as we see from the ungrammaticality of sentences such as:

However, it is interesting to note that in structures like (48) too we find that adverbs belonging to the same class as gently can be positioned either before the verb or between its two complements:

This suggests that (in spite of the fact that the relevant verbs have no intransitive counterpart) a shell analysis is appropriate for structures like (48) too. If so, a sentence such as (48a) will have the structure shown in simplified form in (51) below (with arrows showing movements which take place)

We can then say that the adverb carefully adjoins to v-bar in (50a), and to V-bar in (50b). If we suppose that verbs like load are essentially affixal in nature (in the sense that they must adjoin to a null causative light verb with an AGENT external argument) we can account for the ungrammaticality of intransitive structures such as (49a) ∗The truck will load with hay.

|

|

|

|

بـ3 خطوات بسيطة.. كيف تحقق الجسم المثالي؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

دماغك يكشف أسرارك..علماء يتنبأون بمفاجآتك قبل أن تشعر بها!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تواصل إقامة مجالس العزاء بذكرى شهادة الإمام الكاظم (عليه السلام)

|

|

|