تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

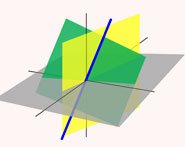

الهندسة

الهندسة

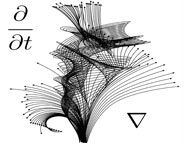

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 22-10-2015

Date: 22-10-2015

Date: 25-10-2015

|

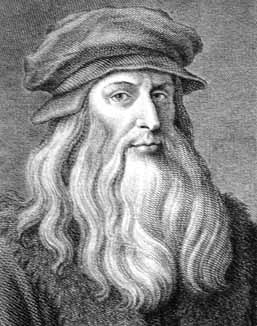

Born: 15 April 1452 in Vinci (near Empolia), Italy

Died: 2 May 1519 in Cloux, Amboise, France

Leonardo da Vinci was educated in his father's house receiving the usual elementary education of reading, writing and arithmetic. In 1467 he became an apprentice learning painting, sculpture and acquiring technical and mechanical skills. He was accepted into the painters' guild in Florence in 1472 but he continued to work as an apprentice until 1477. From that time he worked for himself in Florence as a painter. Already during this time he sketched pumps, military weapons and other machines.

Leonardo da Vinci was educated in his father's house receiving the usual elementary education of reading, writing and arithmetic. In 1467 he became an apprentice learning painting, sculpture and acquiring technical and mechanical skills. He was accepted into the painters' guild in Florence in 1472 but he continued to work as an apprentice until 1477. From that time he worked for himself in Florence as a painter. Already during this time he sketched pumps, military weapons and other machines.

Between 1482 and 1499 Leonardo was in the service of the Duke of Milan. He was described in a list of the Duke's staff as a painter and engineer of the duke. As well as completing six paintings during his time in the Duke's service he also advised on architecture, fortifications and military matters. He was also considered as a hydraulic and mechanical engineer.

During his time in Milan, Leonardo became interested in geometry. He read Leon Battista Alberti's books on architecture and Piero della Francesca's On Perspective in Painting. He illustrated Pacioli's Divina proportione and he continued to work with Pacioli and is reported to have neglected his painting because he became so engrossed in geometry.

Leonardo studied Euclid and Pacioli's Suma and began his own geometry research, sometimes giving mechanical solutions. He gave several methods of squaring the circle, again using mechanical methods. He wrote a book, around this time, on the elementary theory of mechanics which appeared in Milan around 1498.

Leonardo certainly realised the possibility of constructing a telescope and in Codex Atlanticus written in 1490 he talks of

... making glasses to see the Moon enlarged.

In a later work, Codex Arundul written about 1513, he says that

... in order to observe the nature of the planets, open the roof and bring the image of a single planet onto the base of a concave mirror. The image of the planet reflected by the base will show the surface of the planet much magnified.

See [28] for more details of this quotation and more of Leonardo's ideas about the Universe. He understood the fact that the Moon shone with reflected light from the Sun and he correctly explained the 'old Moon in the new Moon's arms' as the Moon's surface illuminated by light reflected from the Earth. He thought of the Moon as being similar to the Earth with seas and areas of solid ground.

In 1499 the French armies entered Milan and the Duke was defeated. Some months later Leonardo left Milan together with Pacioli. He travelled to Mantua, Venice and finally reached Florence. Although he was under constant pressure to paint, mathematical studies kept him away from his painting activity much of the time. He was for a time employed by Cesare Borgia as a

senior military architect and general engineer.

By 1503 he was back in Florence advising on the project to divert the River Arno behind Pisa to help with the siege of the city which the Florentines were engaged in. He then produced plans for a canal to allow Florence access to the sea. The canal was never built nor was the River Arno diverted.

In 1506 Leonardo returned for a second period in Milan. Again his scientific work took precedence over his painting and he was involved in hydrodynamics, anatomy, mechanics, mathematics and optics.

In 1513 the French were removed from Milan and Leonardo moved again, this time to Rome. However he seems to have led a lonely life in Rome again more devoted to mathematical studies and technical experiments in his studio than to painting. After three years of unhappiness Leonardo accepted an invitation from King Francis I to enter his service in France.

The French King gave Leonardo the title of

first painter, architect, and mechanic of the King

but seems to have left him to do as he pleased. This means that Leonardo did no painting except to finish off some works he had with him, St. John the Baptist, Mona Lisa and the Virgin and Child with St Anne. Leonardo spent most of his time arranging and editing his scientific studies.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|