الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

علم البصريات

علم البصريات

الفيزياء الحديثة

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية

الفيزياء النووية

الفيزياء النووية

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الليزر

الليزر

علم الفلك

علم الفلك

المجموعة الشمسية

المجموعة الشمسية

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة البديلة

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء|

أقرأ أيضاً

التاريخ: 2024-02-14

التاريخ: 2-2-2016

التاريخ: 10-3-2021

التاريخ: 2024-02-06

|

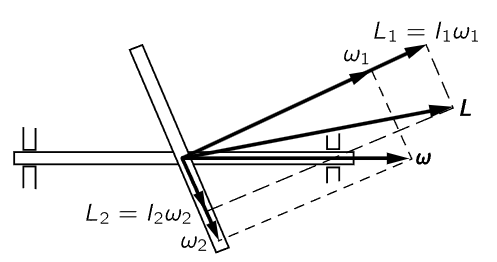

Fig. 20–6. The angular momentum of a rotating body is not necessarily parallel to the angular velocity.

Before we leave the subject of rotations in three dimensions, we shall discuss, at least qualitatively, a few effects that occur in three-dimensional rotations that are not self-evident. The main effect is that, in general, the angular momentum of a rigid body is not necessarily in the same direction as the angular velocity. Consider a wheel that is fastened onto a shaft in a lopsided fashion, but with the axis through the center of gravity, to be sure (Fig. 20–6). When we spin the wheel around the axis, anybody knows that there will be shaking at the bearings because of the lopsided way we have it mounted. Qualitatively, we know that in the rotating system there is centrifugal force acting on the wheel, trying to throw its mass as far as possible from the axis. This tends to line up the plane of the wheel so that it is perpendicular to the axis. To resist this tendency, a torque is exerted by the bearings. If there is a torque exerted by the bearings, there must be a rate of change of angular momentum. How can there be a rate of change of angular momentum when we are simply turning the wheel about the axis? Suppose we break the angular velocity ω into components ω1 and ω2 perpendicular and parallel to the plane of the wheel. What is the angular momentum? The moments of inertia about these two axes are different, so the angular momentum components, which (in these particular, special axes only) are equal to the moments of inertia times the corresponding angular velocity components, are in a different ratio than are the angular velocity components. Therefore, the angular momentum vector is in a direction in space not along the axis. When we turn the object, we have to turn the angular momentum vector in space, so we must exert torques on the shaft.

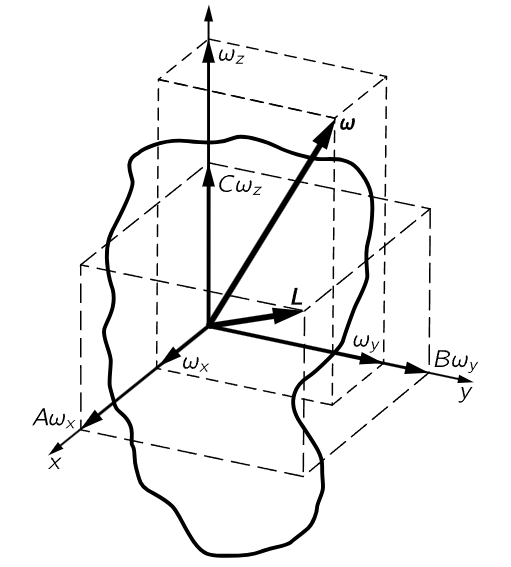

Although it is much too complicated to prove here, there is a very important and interesting property of the moment of inertia which is easy to describe and to use, and which is the basis of our above analysis. This property is the following: Any rigid body, even an irregular one like a potato, possesses three mutually perpendicular axes through the CM, such that the moment of inertia about one of these axes has the greatest possible value for any axis through the CM, the moment of inertia about another of the axes has the minimum possible value, and the moment of inertia about the third axis is intermediate between these two (or equal to one of them). These axes are called the principal axes of the body, and they have the important property that if the body is rotating about one of them, its angular momentum is in the same direction as the angular velocity. For a body having axes of symmetry, the principal axes are along the symmetry axes.

Fig. 20–7. The angular velocity and angular momentum of a rigid body (A>B>C).

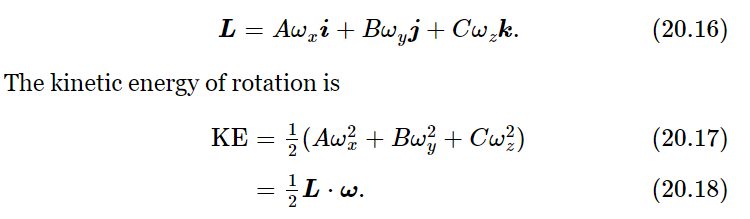

If we take the x-, y-, and z-axes along the principal axes, and call the corresponding principal moments of inertia A, B, and C, we may easily evaluate the angular momentum and the kinetic energy of rotation of the body for any angular velocity ω. If we resolve ω into components ωx, ωy, and ωz along the x-, y-, z-axes, and use unit vectors i, j, k, also along x, y, z, we may write the angular momentum as

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|