Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-07-09

Date: 2023-11-15

Date: 2023-09-18

|

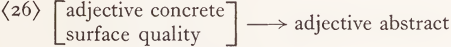

The final case we shall consider involves ‘historical metaphor’. For example, in modern English there is a regular rule (e.g. (26)) which extends surface quality adjectives which are not drawn from a restricted set of abstract qualities. Thus in (27b) the adjective ‘colorful’ is used with the noun ‘ball’ or ‘idea’. Certain adjectives drawn from a restricted set are not affected by rule (26). For example, shapes and colors are not regularly applied to ideas, as can be seen in (27 d). Whenever

shapes are used to modify abstract nouns, as in (27 e) they are defined by our analysis as isolated expressions and not the result of the general metaphor rule in

(27) (a) The ball is colorful

(b) The idea is colorful

(c) The ball is ovoid

(d) *The idea is ovoid

(e) The idea is square

(f) The idea is variegated

This too seems intuitively correct. In The idea is square’ we know that an abstract interpretation of ‘square’ is possible but unique - it is not the result of a general productive rule. In this case we happen to know the unique abstract interpretation of ‘square’ but we do not know how to interpret ‘ovoid’ in ‘the idea is ovoid’. However, prior knowledge of the abstract interpretation of surface quality adjectives is not necessary for their metaphorical interpretation: for example, we may never have heard the sentence ‘the idea is variegated’ before, but we can immediately recognize it as a regular lexical extension of the ‘ literal ’ meaning of ‘ variegated ’ (i.e. ‘ the idea has many apparent components ’).

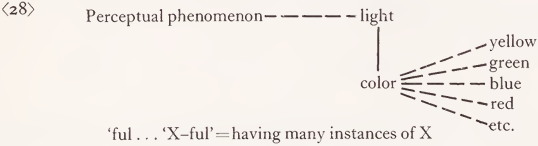

The representation of lexical items in hierarchies facilitates the automatic interpretation of the metaphorical extensions of certain words from their original lexical structure. Consider the lexical analysis of the word ‘colorful’ using the Be and Have hierarchy simultaneously.

Suppose we use the following metaphorical principle:

a metaphorical extension of X includes the hierarchical relations of the literal interpretation without the specific labels:

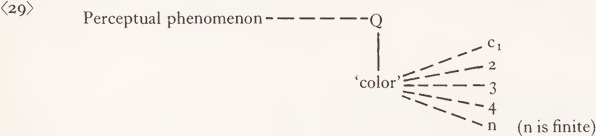

That is, the literal meaning of ‘color’ is extended metaphorically as shown in (29):

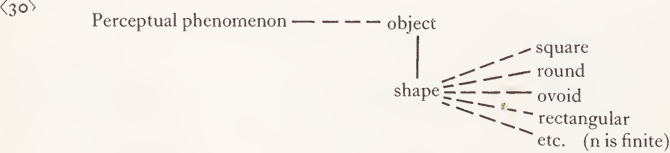

In this way the word ‘colorful’ as applied to ‘idea’ would be automatically interpreted as ‘having simultaneously a large set of potentially distinguishing characteristics’. Similarly, the lexical hierarchical analysis predicts the metaphorical interpretation of ‘ shape ’ in ‘ the idea took shape ’.

In the extended usage ‘shape’ is interpreted as ‘ a particular character out of many (but finite) characters’. Note that although there is an infinite variety of shapes possible, there is a finite number listed in the lexicon: what ‘the idea has shape’ means is that the idea has one clear recognizable characteristic, as opposed to an unnamable characteristic.

Consider now the interpretation of ‘the idea is square’. The lexical metaphor principle applies to (28) to give the interpretation ‘ the idea has a specific characteristic out of a finite list of them’. But there is no special indication as to which characteristic it is, or how it fits into the abstract realm of ideas. Thus it takes special knowledge to interpret the metaphorical extensions of lexical items at the most subordinate part of the hierarchy, if unique knowledge is also required in the original literal interpretation (e.g. that ‘ square ’ is a specific shape).

For these kinds of cases this principle provides a more general rationale for metaphorical interpretation than does the specific rule in (26). It distinguishes cases of metaphor which require no special knowledge (‘ shape, color ’) from those which do (‘ square, green ’). It also offers some insight into the nature of the metaphorical extension itself.

There are many metaphors for which this sort of lexical account will not do. Thus, ‘ the secretary of defense was an eagle gripping the arrows of war, but refusing to loose them ’ is not interpretable in terms of any lexical hierarchy. What we have shown is that the interpretation of ‘ lexical metaphors ’ can be defined in terms of the original literal form of the lexical entry, and that this can distinguish between ‘ regular ’ metaphorical extensions and isolated cases of metaphor.

|

|

|

|

دراسة تكشف "مفاجأة" غير سارة تتعلق ببدائل السكر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أدوات لا تتركها أبدًا في سيارتك خلال الصيف!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تؤكد الحاجة لفنّ الخطابة في مواجهة تأثيرات الخطابات الإعلامية المعاصرة

|

|

|