Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-17

Date: 2025-02-03

Date: 2025-01-31

|

Optimality Theory: An introduction

Optimality Theory is a theory about the organization and nature of grammar, most notably phonology. It is a theory that does not make use of classical derivational rules but of a set of ranked violable well-formedness conditions against which possible output forms are evaluated in parallel. I will outline the basic architecture of this theory, with special focus on those aspects that will be relevant for the discussion of derived verbs in English. Due to this focus the following introduction to OT is necessarily simplified and incomplete. For a more detailed discussion the reader should consult the primary literature (e.g. Prince and Smolensky 1993, McCarthy and Prince 1993b) or the introductory treatments in Archangeli and Langendoen (1997) or Sherrard (1997), for example.

In OT, Universal Grammar (UG) provides a set of well-formedness conditions, called constraints, from which grammars are constructed. The grammar of a particular language consists of an ordered ranking of these constraints, which is specific to this language. The grammars of other languages are characterized by different constraint rankings. How do these constraints operate? Given an underlying representation as input, a component of UG (called Gen) generates a whole range of possible outputs (so-called candidates) of which the one is chosen as optimal which best satisfies the constraints.

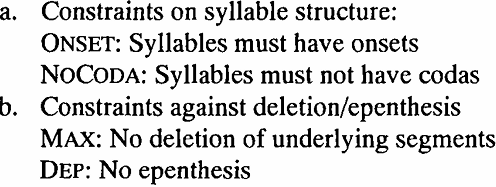

What mainly differentiates OT from other non-derivational theories is the assumption that the constraints are violable. The hierarchical ranking of the constraints ensures that a constraint must always be satisfied unless doing so would involve the violation of a more important constraint. For illustration consider the surface realizations and syllabifications of the input forms /tata/, /pap/ and /aka/ in a given language L. For the sake of the argument, let us assume that only two constraints are responsible for syllabification, ONSET and NOCODA (e.g Prince and Smolensky 1993), and that there are two constraints that work against the deletion or epenthesis of segments, MAX and DEP (McCarthy and Prince 1995):

(1)

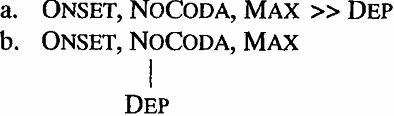

Let us further assume that in language L ONSET, NOCODA and MAX are ranked higher than DEP. Such rankings are usually expressed as in (2a) or (2b):

(2)

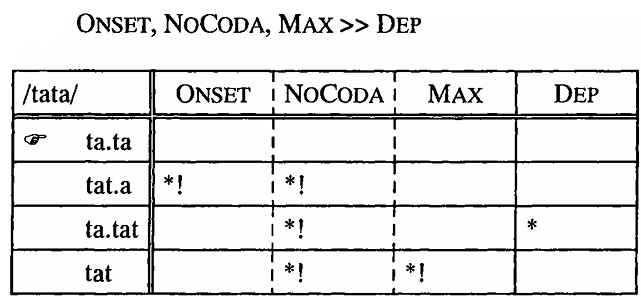

Considering first only four likely output candidates for the input /tata/, we can construct a tableau as in (3) below, which shows the computation of the optimal candidate. A few notational conventions are necessary for the interpretation of an OT tableau. The output candidates are listed in the leftmost column, with the optimal candidate being marked by the pointing hand ('☛'). Violations are marked by an asterisk and exclamation marks indicate fatal constraint violations, i.e. those which eliminate a candidate. The optimal candidate is the one that rates better on the higher constraints than the competing candidates. If two candidates both violate the same high constraint, the decision is passed on to the next lower constraint. Solid lines between colomns indicate hierarchical ranking, broken lines are used between constraints that are not ranked with respect to each other.

(3)

In (3), [ta.ta] is the optimal candidate because it violates none of the constraints in the tableau. All other candidates violate at least one constraint and are therefore ruled out. The syllabification tat.a, for example, is illicit due to the filled coda of the first syllable (i.e. a NOCODA violation) and the onsetless second syllable (i.e. an ONSET violation). Note that in our example [ta.ta] emerges as the optimal candidate under any ranking of the constraints because it violates none of them. The next sample input /pap/ shows, however, that the ranking is crucial for the selection of the optimal output:

(4)

In (4) [pa.pa] is selected as the optimal candidate, because the high rank of NOCODA necessitates either vowel epenthesis or deletion of the final consonant. Since the constraint against deletion (i.e. MAX) is higher-ranked than the constraint against epenthesis (i.e. DEP), the DEP violation is more easily affordable than the MAX violation. Under a different ranking, another candidate is optimal. For example, if DEP were ranked higher than MAX, vowel epenthesis would be ruled out, and the candidate involving a MAX violation would emerge as optimal. If both MAX and DEP were ranked above NOCODA, [pap] would be optimal.

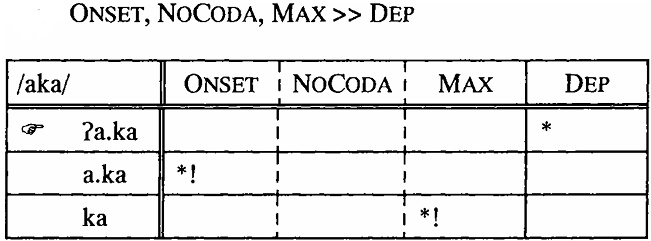

The last example shows how constraint violation becomes unavoidable because of conflicting constraints. Given a consonant-final input form, it is impossible to have CV syllables without either epenthesis or deletion, satisfying high-ranked NOCODA. Thus, of the three constraints NOCODA, MAX and DEP, two can be satisfied at the expense of the third, but never all three of them at the same time. Let us finally consider the input /aka/:

(5)

With the given input in (5), ONSET requires either deletion or epenthesis. The higher rank of MAX again leads to epenthesis as the preferred repair strategy.1 Ranking both MAX and DEP higher than ONSET would make [aka] the optimal candidate.

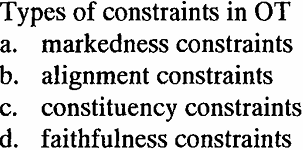

Having outlined the basic machinery, we may now turn to the nature of constraints in more detail. Obviously, one of the central problems in OT is to constrain the use of constaints in some way or another. Which constraints should be allowed in the theory and which others should be ruled out? Ideally, each constraint can be motivated on cross-linguistic grounds. Thus the constraints against filled codas and for filled onsets mirror the crosslinguistic tendency towards CV as the unmarked syllable structure (e.g. Jakobson 1962, Vennemann 1988, Blevins 1995) and have been used to establish a factorial typology of syllabic structures (Prince and Smolensky 1993: chapter 6). Unfortunately, not all constraints that can be found in the literature have been justified in an equally satisfactory manner and a good deal of the present discussion in OT is devoted to this question. Currently the following types of constraints are widely acknowledged:

(6)

Markedness constraints reflect the preference for certain types of structures. For example, it has been suggested that, cross-linguistically, obstruents make better syllable margins than sonorant consonants or vowels. This fact can be formalized in OT as a hierarchy of constraints against certain types of syllable margins (M), according to their sonority, as in (7) (cf. Prince and Smolensky 1993):

(7)

A more detailed discussion of markedness constraints is not necessary for the purposes of this study.

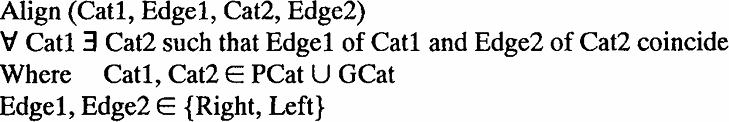

Let us therefore turn to alignment constraints, which regulate the adjacency or coincidence of linguistic objects. Alignment constraints are frequently used to analyze the metrical behavior of words. The general format of alignment constraints is given in (8), with a perhaps more accessible formulation in (9) (see McCarthy and Prince 1993a):

(8)

(9)

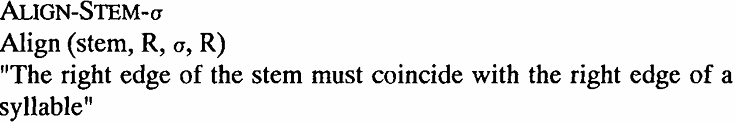

To give only one illustrative example, consider the syllabification of the word helpless. Most native speakers would probably agree that the syllable boundary should be placed between help and less (help. less). However, in terms of the standard syllabification principles of English, we would expect hel.pless instead, because both hel and pless are well-formed syllables and because this syllabification would better satisfy the maximal onset principle (Selkirk 1982b). Compare, for instance im.ply and *imp.ly, com.plain and *comp.lain, which illustrate this point. What these examples show is that syllabification interacts with morphology in such a way that with words such as helpless, the morphological boundary must coincide with the a syllable boundary. In the theory of generalized alignment (McCarthy and Prince 1993a), this can be achieved by the high ranking of the pertinent alignment constraint ALlGN-Stem-σ as against the lower ranking of the constraints that ensure maximal onsets:

(10)

For the vowel-initial verbal suffixes such a constraint does not play a crucial role, since in these derivatives the stem-final consonant (if not truncated) fills the onset position of the last syllable, as exemplified by wea.ken, fe.de.ra.lize, per.so.ni.fy, hy.phe.nate. This means that ONSET is ranked higher than ALIGN-STEM-σ.

Constituency constraints refer to the prosodie hierarchy (e.g. Nespor and Vogel 1986) and govern the extent to which, for example, syllables are dominated, or 'parsed', by feet, feet by prosodic words, etc. Such constraints are especially relevant for an analysis of extrametricality. For example, a trisyllabic input can be footed in several ways. Under the assumption that footing proceeds from left to right and that feet must be either mono- or disyllabic, but not trisyllabic, there is one completely footed candidate (σσ)(σ)2 and one 'extrametrical' candidate (σσ)σ. Footing from left to right is achieved by the alignment constraint ALLFEETLEFT (short for Align (Ft, L, PrWd, L)3), the parsing of syllables into feet by PARSE-Σ ("All syllables are parsed into feet"). The choice of the optimal candidate now depends on the ranking of these two constraints (ceteris paribus)·.

(11)

σ σ!4

(12)

The tableaux show that unparsed syllables are only allowed if PARSE-σ is ranked below ALLFEETLEFT. Under such a ranking PARSE-σ needs to be violated in order to satisfy the more important ALLFEETLEFT.

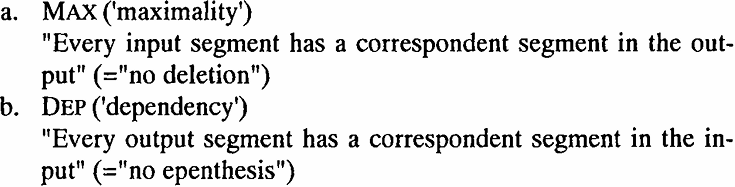

Let us turn to the family of constraints that can be considered the most important in the context of this study, faithfulness constraints. These constraints regulate the degree of identity which ideally exists between input and output. Thus, traditional rule-based analyses (e.g. SPE) have often been criticized as implausible on the grounds that many of the proposed underlying representations were too far removed from their respective surface forms, a problem that has become known as the problem of abstractness. Much of the most recent OT literature is devoted to a principled solution of this problem in terms of a sub-theory called correspondence theory (McCarthy and Prince 1995).

The essence of faithfulness between input and output is that both members should be identical, which is achieved mainly by the constraints MAX and DEP, which we have used already above and which we can now define in a more appropriate fashion in terms of correspondence theory:

(13)

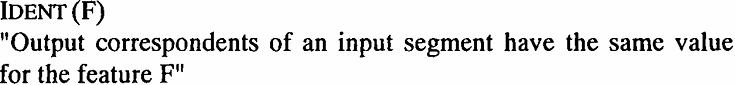

Featural identity between input and output is achieved by parametrized constraints of the family IDENT (F), where F stands for a distinctive feature:

(14)

A number of additional input-output (I-O) faithfulness constraints have been proposed to account for other kinds of correspondence relations between input and output, for example constraints against metathesis, but we will not discuss those any further (see for example McCarthy and Prince 1995: Appendix A for an overview).

Let us turn instead to another type of faithfulness that only very recently has attracted the attention of researchers, namely output-output (O-O) faithfulness. 0-0 faithfulness has been employed in a growing number of studies (e.g. Alber 1998, Alderete 1995, Benua 1995, 1997, Kager 1997, Kenstowicz 1996, McCarthy 1995, Pater 1995) to account for some intriguing morpho-phonological phenomena. It will be shown that 0-0 faithfulness is also of crucial importance for the phonological effects that can be observed with derived verbs in English. To mention only one illustrative example that has nothing to do with derived verbs, consider truncated hypocoristics in English. Benua (1995) observed that the truncated form of Larry (and similar forms) is pronounced [læɹ] in many dialects of American English, although in these dialects the low front vowel [æ] ordinarily does not occur before a tautosyllabic [ɹ]. Consider, for example, [kɑɹ]/[kɑɹd]/*[kæɹ]/*[kæɹd] as against [kae.ɹɪ]. In other words, truncated words are exempt from constraints on vowel quality in syllables with a rhotic coda. Why should this be the case? The answer to this question lies in the simple but fundamental insight that derived words have to be sufficiently similar to the words they are derived from. For our example this means that the constraint which ensures surface similarity (i.e. O-O vowel identity) between Larry and Lar must rank higher than the phonological constraints which prohibit the occurrence of [æɹ.].

Having briefly outlined the basic concepts of OT we may now turn the analysis of derived verbs in English. As we will proceed, a number of problems concerning the ranking and the nature of the constraints involved with these classes of words will be discussed in more detail.

1 Essentially, this is the kind of situation we find in a language like German, where underlyingly vowel-initial syllables in certain prosodic positions (i.e. word- or foot-initial) are realized with a glottal stop in onset position (see, for example, Wiese 1996a:58-60 for discussion).

2 I adopt the standard convention that parentheses indicate feet.

3 Ft=foot, PrWd=prosodic word, L=left, R=right

4 Two sigmas indicate that the offending foot is two syllables from the left margin of the prosodic word.

|

|

|

|

دراسة: حفنة من الجوز يوميا تحميك من سرطان القولون

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تنشيط أول مفاعل ملح منصهر يستعمل الثوريوم في العالم.. سباق "الأرنب والسلحفاة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الطلبة المشاركون: مسابقة فنِّ الخطابة تمثل فرصة للتنافس الإبداعي وتنمية المهارات

|

|

|