Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-12-05

Date: 2023-10-11

Date: 2023-10-05

|

Previous analyses

In the literature there are four studies that describe the phonology of -ize derivatives in some detail: Gussmann 1987, E. Schneider 1987, Kettemann 1988, and Raffelsiefen 1996.

In his article on deadjectival -ize,1 Gussmann focuses on the segmental structure of the base words and proposes that the suffix attaches to "Latinate adjectives ending in a vowel followed by one or more sonorant consonants" (1987:95). On the same page, some counterexamples are presented (stabilize, malleablise,2 legitimatize, objectivize, collectivise3), but Gussmann dismisses them as being "very infrequent" and thus "in the permanent lexicon" (1987:95). In addition to the most frequent sonorants [I, r, n] Marchand lists [s] as the next frequent segment, and [t], [d] and [m] as the least frequent segments preceding -ize, which at least partially refutes Gussmann's claims, since three of the seven segments mentioned are obstruents, not sonorants. In the neologism corpus, more counterexamples to Gussmann's generalization are revealed. Among the derivatives with adjectival bases we find absolutize, academicize (and many more in -ic-ize),4comprehensivize (and many more in -ive-ize), finitize, infinitize, instantize, permanentize, polyploidize, privatize, rigidize, ruggedize. With denominal derivatives even vowels are attested as final segments with a number of bases (e.g. ghettoize, virtuize). The great number of attested forms and their regularity (-ic-ize, -ive-ize) is a strong indication that Gussmann's rule is too restrictive with respect to the base-final segment. As we will shortly see, it is also too weak in that it does not take into account restrictions of a prosodic nature, which, as shown by Raffelsiefen (1996), are much more pervasive for the distribution of -ize than segmental restrictions.

In his brief but insightful remarks on the phonology of -ize derivatives (1987:102ff), E. Schneider states that there are no restrictions concerning the base-final segments, but detects some interesting facts relating to the prosodic structure of the words from which -ize words are derived. On the basis of his corpus of 744 items he finds a strong tendency towards poly-syllabic base words (only 5 monosyllabic stems, as in dockize), and an equally strong tendency towards antepenultimate stress, with only sporadic stress shift. Disyllabic bases are usually consonant-final, with two exceptions, heroize and zeroize. Unstressed base-final vowels of trisyllabic words are deleted {summary - summarize) and base-final secondary stress is often reduced (fèrtile - fértilìzé). Finally, E. Schneider finds peculiar allomorphy effects with Greek bases (e.g. system-systematize) including stress shift (e.g. plátitude-platitúdinize). In sum, in spite of its brevity, E. Schneider's account is very detailed and empirically well-founded. However, no attempt is made to provide a unified explanation for the observed facts. Furthermore, the large data-base including a high number of long-established forms brings in so many idiosyncratic forms that we are faced with an abundance of counterexamples to the proposed generalizations. Hence, E. Schneider comes to the conclusion that the properties of -ize (and of the other suffixes he investigates) can only be described in terms of quantitative tendencies, but not as categorical (1987:109). As we will see below, it is possible to provide a more adequate account of the phonology of -ize derivatives by restricting one's data-base to recent formations.

Kettemann's book (1988) deals with the phonological alternations triggered by derivational affixes in English. He accounts for the alternations in -ize formations either by introducing phonological rules or by assigning the alternation to the word's individual lexical entry. For example, he states that stress shift in the base should be assigned to the individual lexical entry of the word (p. 207), but for the majority of the segmental alternations he proposes phonological rules, such as [∅ ↔ n] for the alternation in the pair Plato - platonic (p. 210). While he can describe most existing derivatives in this manner, his model is unable to predict whether a given base will undergo a certain alternation, and if so, which kind of phonological or phonetic change can be expected. Thus, from his list of possible segmental alternations it is not clear which morphophonological conditions trigger the observed alternation, or, in those cases in which the trigger is mentioned, it is not said whether the alternation is obligatory. Indeed, in many cases it is not. In sum, the phonological description of -ize derivatives in Kettemann (1988) is insufficient in its generalizations and predictive power.

We will now turn to the most detailed and sophisticated account of the phonology of -ize to date, Raffelsiefen (1996). She correctly notes that "Although the rule [of -ize suffixation] is generally productive, it almost never applies to monosyllabic or iambic words" (see also Goldsmith 1990:270 for a similar statement). Thus, words like obscène or secu̕re cannot take -ize as a suffix, contrary to the predictions in Gussmann. Note that Kettemann's model does not make any predictions at all here. Using violable OT-type constraints, Raffelsiefen proposes a number of ranked phonological constraints that are held responsible for the shape of -ize derivatives and the gaps that arise from these constraints. In the following I will first summarize her findings and then show that her account is not sophisticated enough to explain all problematic data.

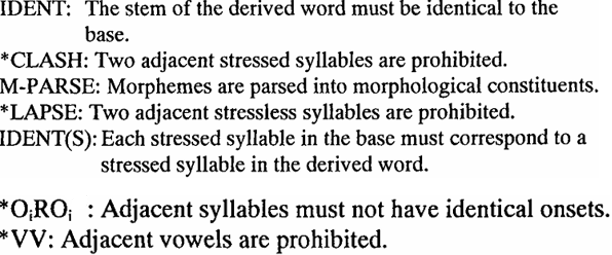

Raffelsiefen's constraints are given in (1):

(1)

OiROi5

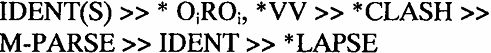

The constraints are ranked as in (2):

(2)

* LAPSE is the lowest constraint in the hierarchy because it can easily be violated by -ize formations (e.g. féderalìze). The IDENT constraints ensure that candidates that preserve the segmental and prosodic make-up of the base are preferred to those candidates that do not. M-PARSE ensures that with certain derivatives the morphologically unparsed candidate is optimal, to the effect that words of this kind cannot be derived. For instance, Prince and Smolensky (1993:49) argue that the impossibility of attaching the comparative suffix -er to words of more than one foot, such as violet, is due to the fact that the violation of the one-foot constraint is evaded by not attaching -er at all. In Raffelsiefen's model, M-PARSE ensures that unaffixed structures are preferred to ones involving, for example, a stress clash. * CLASH prohibits forms such as corrúptize, thus naturally accounting for the fact that -ize almost never attaches to monosyllabic and iambic words. *VV is responsible that, for example, base-final [ɪ] is truncated in words like mémorìze or su̒mmarize. The fact that mémorize is a better candidate than mémoryìze is expressed by ranking *VV over IDENT in the hierarchy. *O¡ROi prohibits forms like *màximumìze or *fémininìze, which both have identical onsets in their last two syllables.6 The strongest constraint is IDENT(S) which dictates that the stress pattern of the base word is not altered by the suffixation of -ize. The high rank of IDENT(S) as against the low rank of IDENT is responsible for the fact that stem allomorphy in the form of loss of base-final segments is rather frequent, but stress shift is virtually impossible. In other words, phonetic material of the base can be rather freely truncated, but the prosody of the base remains largely intact.

These constraints can account quite elegantly for a wide range of problematic or non-occurring -ize formations, thereby showing that many of the lexical gaps are systematic in nature. Nevertheless, Raffelsiefen's analysis is not entirely convincing, for the following reasons:

- The constraints are both too weak and too strong, because they still allow structures that are systematically impossible, and they rule out structures that appear to be systematic.

-Sometimes contradictory constraint rankings are necessary to explain certain subsets of data.

- Some striking regularities are unconvincingly treated as idiosyncrasies.

-A number of additional constraints are mentioned by Raffelsiefen in footnotes, but it is unclear how they can be incorporated into the overall model.

- The constraints are not integrated into a more general model of English prosodic morphology.7

I will illustrate the main problems of Raffelsiefen's approach by discussing a much wider range of data than any of the previous authors (apart from E. Schneider, see above). It will become clear that some striking regularities have gone unnoticed by these authors, and that their approaches cannot account for them. Based on these regularities, I will propose a more fine-tuned model of prosodic constraints later.

1 In the subsequent discussion, we will not distinguish between deadjectival and denominal -ize derivatives because this distinction is neither phonologically not semantically relevant.

2 The forms stabilise and malleablise only count as counterexamples on the assumption that the base words end in syllabic /l/.

3 The examples are cited in the orthographical form of the original.

4 According to Gussmann, -ic is generally truncated. The OED data refute this statement. For a more detailed discussion of truncation see below.

5 In Raffelsiefen's notation, Ό' stands for onset and 'R' for rhyme.

6 The derivative memorize also violates *O¡RO¡, but since all likely candidates equally violate the constraint, memorize is the optimal candidate (in view of the other constraints).

7 I use the term 'prosodic morphology' in the wide sense of McCarthy and Prince (1998:283) as referring to "a theory of how morphological and phonological determinants of linguistic form interact with one another in grammatical systems".

|

|

|

|

خطر خفي في أكياس الشاي يمكن أن يضر صحتك على المدى البعيد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ماذا نعرف عن الطائرة الأميركية المحطمة CRJ-700؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الأمين العام للعتبة العلوية المقدسة يستقبل المتولّي الشرعي للعتبة الرضوية المطهّرة والوفد المرافق له

|

|

|