Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 1-3-2022

Date: 2024-01-23

Date: 2024-01-20

|

Variable telicity in degree achievements - Telicity and structure

Our discussion of Abusch’s work shows that any account of DAs must explain three factors: 1) the (strong) default telic/positive interpretation of verbs like darken, 2) the lack of a telic/positive meaning for verbs like widen, and 3) the differential interpretation assigned to measure phrase arguments. Recent analyses of DAs have attempted to account for these factors by adopting a semantics for DAs that is more directly “scalar,” importing features from degree-based semantic analyses of gradable adjectives. We hold off on providing a full overview of scalar semantics until later sections when we introduce our own account (which is also a scalar one); here we highlight the crucial advantages – and shortcomings – of existing scalar analyses.

The first explicitly scalar analysis of DAs, and the one on which the analysis will be based on, is provided by Hay et al. (1999). Hay et al. provide in effect a purely “comparative” semantics for DAs, treating them as predicates of events that are true of an object if the degree to which it possesses the gradable property encoded by the source adjective at the end of the event exceeds the degree to which it possessed that property at the beginning of the event by some positive degree d. The degree argument, which Hay et al. refer to as the difference value, is a measure of the amount that an object changes as a result of participating in the event described by a DA, and is precisely that which is overtly expressed by the measure phrases that were problematic for Abusch’s analysis. The meanings assigned to these examples in the Hay et al. analysis are exactly those specified above in, thus solving one of the three problems.

The difference value is furthermore the crucial factor determining the telicity of the predicate. If it is such that a particular degree on the adjectival scale must be obtained in order for the predicate to be true of an event, then a terminal point for the entire event can be identified, namely that point at which the affected object attains that degree (which is equivalent to the initial degree to which it possessed the property plus the degree specified by the difference value); the result is a telic interpretation. If, however, the difference value is satisfied by any positive degree, this computation isn’t possible and no terminal point can be identified; in this case, the predicate is atelic.

In some cases, such as the examples with measure phrases above, the difference value is explicit and the predicate is telic. When the difference value is implicit, contextual and lexical semantic factors determine its value and in turn the telicity of the predicate. Hay et al. take advantage of the latter to explain the different aspectual properties of DAs like widen and deepen on the one hand, and those like darken, dry, and empty on the other. In particular, they observe that these two classes of DAs differ with respect to the structures of the scales associated with their adjectival bases: wide, deep, etc. use open scales (scales that lack maximal elements); dark, dry, etc. use closed ones (scales with maximal elements).

According to Hay et al., verbs derived from closed scale adjectives are by default telic due to a preference for fixing the difference value in such a way as to entail that the maximal value on the scale must be reached. In effect, since the structure of the scale allows for the possibility of increase along the adjectival scale to a maximal degree (“maximal change”), and such a meaning is stronger than (entails) all other potential meanings, it should be selected, resulting in a telic interpretation. This explanation has obvious similarities to the account of default telicity presented above in the context of Abusch’s analysis; where the Hay et al. proposal stands apart is in the explanation of obligatory atelicity for DAs derived from open scale adjectives like widen. Because the adjectival root wide uses a scale that does not have a maximal degree, there is no possibility for an interpretation involving maximal change, so the difference value is existentially closed. The result is that widen is true of an event and an object as long as it undergoes some increase in width, which derives an atelic interpretation.

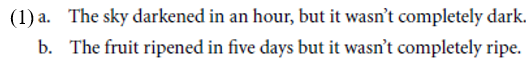

Similar analyses have been developed by Kearns (2007) and Winter (2006), which differ slightly in detail but ultimately face a similar challenge. To set the stage for this challenge, we must first address a specific criticism of Hay et al.’s account of default telicity for verbs based on closed scale adjectives, discussed in Kearns (2007). Kearns argues that the telos for such verbs need not be a maximum value on the relevant scale, but is rather the standard used by the corresponding adjective, whatever that is. As support for this claim, she presents examples like (1a–b) to show that the telic interpretations of Das based on (unmodified) closed scale adjectives do not actually entail maximality, as indicated by the acceptability of the not completely continuations (numbers in square brackets refer to the example numbers in Kearns 2007).

While we agree with Kearns’ claim that the telos for verbs like darken and ripen should be identified with the standard of the corresponding adjectives (and that the Hay et al. analysis fails to adequately explain this connection), we do not agree that the data in (1) show that this value is not a maximal degree on the relevant scales. Instead, we claim that the apparent non-maximality of the adjectival standards in the second conjuncts of (1a–b) is an artifact of the fact that the definite descriptions that introduce the affected arguments in the first conjuncts can be interpreted imprecisely, allowing for the possibility that the verbs do not apply to subparts of the objects that the descriptions are used to refer to. In other words, what is being denied in the second conjunct of (1a) is that all parts of the sky are dark, not that the parts of the sky that the verb does in fact apply to fail to become maximally dark.

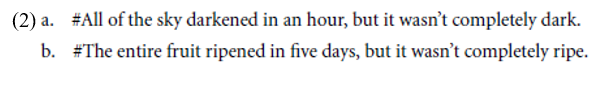

Evidence in favor of this interpretation of the data in (1) comes from a couple of sources. First, if we eliminate the possibility of an imprecise interpretation of the definite in the first conjunct by making it explicit that the entire object is affected, we get a contradiction with a not completely interpretation:

These examples show that the second conjunct can have an interpretation in which the adverb is in effect modifying the subject (not all of it) rather than picking out a maximal value on the scale, which in turn shows that Kearns’ examples do not counterexemplify Hay et al.’s claims that telic DAs entail maximum degrees.

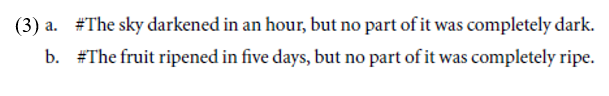

Second, if we modify the second conjunct to make it explicit that the intended interpretation is one in which a maximal degree is not achieved, we get a contradiction:

These examples provide positive evidence that telic DAs like darken and ripen do in fact entail that their affected arguments achieve maximal degrees of the properties measured by the adjectives. If this were not the case, then there would be no incompatibility between the two conjuncts: the assertion that no part of the sky is completely dark in the second conjunct of (3a), for example, should be perfectly consistent with the first conjunct if the verb merely required something close to complete darkness for whatever parts of the sky (possibly all of them) are assumed to be affected.

These considerations show that telic interpretations of DAs based on closed scale adjectives do in fact entail movement to a maximal degree, contrary to Kearns’ claims; however, they do not argue against her position that the telos is the “standard endstate” associated with the adjectival form, if in fact the adjectival standard is itself a maximal degree.1 This position is in fact argued for in detail by Rotstein and Winter (2004), Kennedy and McNally (2005) and Kennedy (2007), a point that we will discuss in detail in the next section. Although this result is not inconsistent with Hay et al.’s analysis, it is important to acknowledge that the analysis does not actually derive it in a principled way.

The problem is that Hay et al. do not provide an explicit mechanism for fixing the difference value for verbs like darken, ripen, etc. in such a way as to ensure that the predicate actually entails of its argument that it becomes maximally dark, ripe, etc., saying only that the existence of a maximal value on the scale “provides a basis” for fixing the difference value in the appropriate way (see Pinon’s contribution to this volume for detailed discussion of this point). This problem threatens to undermine the whole analysis: without a principled account of the conditions under which the difference value can and cannot correspond to particular degrees, we lose the explanation of the difference in (default) telicity between DAs derived from adjectives with open scales and those derived from adjectives with closed scales. In short, we have no explanation of why it is possible to fix the difference value to a degree that entails movement to the end of the scale in the case of the latter class of DAs, but not possible to fix the difference value to a degree that entails movement to a contextual standard in the case of the former class (see Kearns 2007 for the same criticism). Such a move would result in a telic interpretation of, for example, widen with a meaning comparable to become wide, which as we have shown is not an option (or is at best a highly marked one).

Kearns’ solution to this problem is to claim that the contextual standard associated with adjectives like wide is “insufficiently determined” to serve as a telos. Although this explanation has intuitive appeal, it seems unlikely given the fact that become wide is telic, and more generally, given the fact that speakers must have access to the contextual standard in order to assign truth conditions to sentences containing the positive form of the adjective. Winter (2006) takes a different approach: he defines the mapping from scalar adjectives to (corresponding) DAs in such a way that the verbal form has a telos based on a lexically specified adjectival standard if one is specified, and (building on proposals in Rotstein and Winter 2004) posits that such standards are specified only for closed scale adjectives. While this analysis achieves the desired result, it has a couple of undesirable features. First, it simply eliminates the possibility of a contextual standard by stipulation; an analysis in which this restriction follows from more general principles is preferable. Second, it predicts that DAs based on closed scale adjectives like straighten should have only telic interpretations, since in the Rotstein and Winter semantics for scalar adjectives, straight is specified as having a standard associated with the endpoint of the scale. The fact that DAs based on closed scale adjectives can also have atelic interpretations (see note 4 and Kearns 2007) then remains unexplained.

At a more general level, Winter’s analysis raises the question of why it is just the closed scale adjectives that are conventionally associated with fixed standards. If we can answer this question, and also provide an answer to the question of why fixed standards can give rise to telic interpretations of Das while context-dependent ones (of the sort involved in the interpretation of an open scale adjective like wide) cannot, then we will have the basis for a truly explanatory account of the relation between scale structure and telicity in DAs. In the next section we present an analysis of the semantics of degree achievements in which the answers to these two questions are in fact the same.

1 Kearns is correct that the DA cool – and presumably some others like it – has a conventionalized non-maximal endpoint. When this verb is used telically without context, as in (i), the endpoint is assumed to be room temperature, presumably because food normally can’t cool further without being put in a refrigerator or in some other cold place.

(i) The soup cooled in ten minutes.

We discuss the case of cool in more detail below.

|

|

|

|

تحذير من "عادة" خلال تنظيف اللسان.. خطيرة على القلب

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

دراسة علمية تحذر من علاقات حب "اصطناعية" ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تحذّر من خطورة الحرب الثقافية والأخلاقية التي تستهدف المجتمع الإسلاميّ

|

|

|