النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Mammalian Satellites Consist of Hierarchical Repeats

المؤلف:

JOCELYN E. KREBS, ELLIOTT S. GOLDSTEIN and STEPHEN T. KILPATRICK

المصدر:

LEWIN’S GENES XII

الجزء والصفحة:

18-3-2021

3494

Mammalian Satellites Consist of Hierarchical Repeats

KEY CONCEPT

Mouse satellite DNA has evolved by duplication and mutation of a short repeating unit to give a basic repeating unit of 234 bp in which the original half-, quarter-, and eighth-repeats can be recognized.

In mammals, as typified by various rodent species, the sequences comprising each satellite show appreciable divergence between tandem repeats. Researchers can recognize common short sequences by their preponderance among the oligonucleotide fragments produced by chemical or enzymatic treatment. However, the predominant short sequence usually accounts for only a small minority of the copies. The other short sequences are related to the predominant sequence by a variety of substitutions, deletions, and insertions.

However, a series of these variants of the short unit can constitute a longer repeating unit that is itself repeated in tandem with some variation. Thus, mammalian satellite DNAs consist of a hierarchy of repeating units that can be detected by reassociation analyses or restriction enzyme digestion.

When any satellite DNA is digested with an enzyme that has a recognition site in its repeating unit, one fragment will be obtained for every repeating unit in which the site occurs. In fact, when the DNA of a eukaryotic genome is digested with a restriction enzyme, most of it gives a general smear due to the random distribution of cleavage sites. However, satellite DNA generates sharp bands because a large number of fragments of identical or almost identical size are created by digestion at restriction sites that lie a regular distance apart.

Determining the sequence of satellite DNA can be difficult. For example, researchers can cut the region into fragments with restriction endonucleases and attempt to obtain a sequence directly. However, if there is appreciable divergence between individual repeating units, different nucleotides will be present at the same position in different repeats, so the sequencing gels will not clearly identify the sequence. If the divergence is not too great—say, within about 2%—it might be possible to determine an average repeating sequence.

Individual segments of the satellite can be inserted into plasmids for cloning. A difficulty is that the satellite sequences tend to be excised from the chimeric plasmid by recombination in the bacterial host. However, when the cloning succeeds it is possible to determine the sequence of the cloned segment unambiguously.

Although this gives the actual sequence of a repeating unit or units, we would need to have many individual such sequences to reconstruct the type of divergence typical of the satellite as a whole.

Using either sequencing approach, the information we can gain is limited to the distance that can be analyzed on one set of sequence gels. The repetition of divergent tandem copies makes it difficult to reconstruct longer sequences by obtaining overlaps between individual restriction fragments.

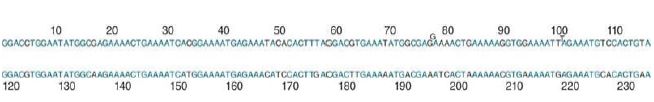

The satellite DNA of the mouse M. musculus is digested by the enzyme EcoRII into a series of bands, including a predominant monomeric fragment of 234 bp. This sequence must be repeated with few variations throughout the 60% to 70% of the satellite that is digested into the monomeric band. Researchers can analyze this sequence in terms of its successively smaller constituent repeating units.

FIGURE 1 depicts the sequence in terms of two half-repeats. By writing the 234-bp sequence so that the first 117 bp are aligned with the second 117 bp, we see that the two halves are quite similar. They differ at 22 positions, corresponding to 19% divergence. This means that the current 234-bp repeating unit must have been generated at some time in the past by duplicating a 117-bp repeating unit, after which differences accumulated between the duplicates.

FIGURE 6.13 The repeating unit of mouse satellite DNA contains two half-repeats, which are aligned to show the identities (in blue).

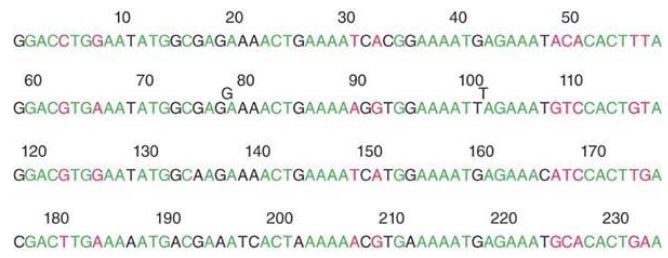

Within the 117-bp unit we can recognize two further subunits. Each of these is a quarter-repeat relative to the whole satellite. The four quarter-repeats are aligned in FIGURE 2. The upper two lines represent the first half-repeat of Figure 2; the lower two lines represent the second half-repeat. We see that the divergence between the four quarter-repeats has increased to 23 out of 58 positions, or 40%. The first three quarter-repeats are somewhat more similar and a large proportion of the divergence is due to changes in the fourth quarter-repeat.

FIGURE 2 The alignment of quarter-repeats identifies homologies between the first and second half of each half-repeat.

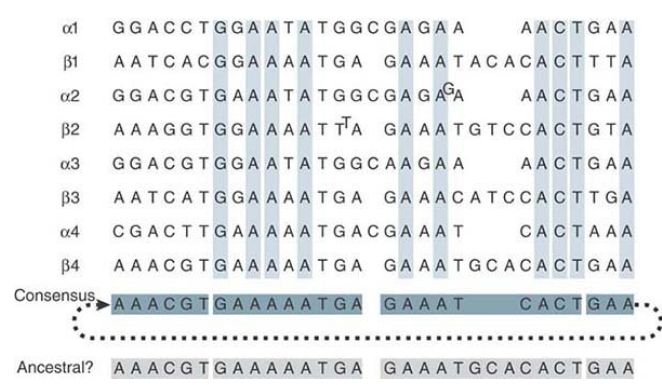

Positions that are the same in all four quarter-repeats are shown in green. Identities that extend only through three-quarters of the quarter-repeats are in black, with the divergent sequences in red. Looking within the quarter-repeats, we find that each consists of two related subunits (one-eighth-repeats), shown as the α and β sequences in FIGURE 3. The α sequences all have an insertion of a C and the β sequences all have an insertion of a trinucleotide sequence relative to a common consensus sequence. This suggests that the quarter-repeat originated by the duplication of a sequence like the consensus sequence, after which changes occurred to generate the components we now see as α and β.

Further changes then took place between tandemly repeated αβ sequences to generate the individual quarter- and half-repeats that exist today. Among the one-eighth-repeats, the present divergence is 19/31 = 61%.

FIGURE 3 The alignment of eighth-repeats shows that each quarter-repeat consists of an α and a β half. The consensus sequence gives the most common base at each position. The “ancestral” sequence shows a sequence very closely related to the consensus sequence, which could have been the predecessor to the α and β units. (The satellite sequence is continuous so that for the purposes of deducing the consensus sequence we can treat it as a circular permutation, as indicated by joining the last GAA triplet to the first 6 bp.)

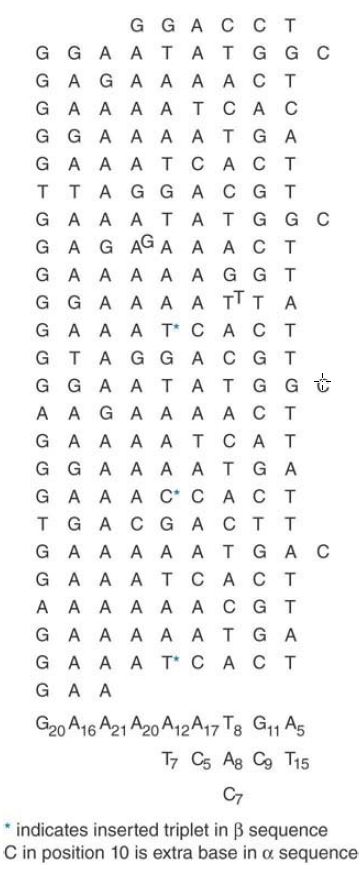

The consensus sequence is analyzed directly in FIGURE 4, which demonstrates that the current satellite sequence can be treated as derivatives of a 9-bp sequence. We can recognize three variants of this sequence in the satellite, as indicated at the bottom of the figure. If in one of the repeats we take the next most frequent base at two positions instead of the most frequent, we

obtain three similar 9-bp sequences:

G A A A A A C G T

G A A A A A T G A

G A A A A A A C T

The origin of the satellite could well lie in an amplification of one of these three nonamers (9-bp units). The overall consensus sequence of the present satellite is , which is effectively an amalgam of the three 9-bp repeats.

, which is effectively an amalgam of the three 9-bp repeats.

FIGURE 4 The existence of an overall consensus sequence is shown by writing the satellite sequence as a 9-bp repeat.

The average sequence of the monomeric fragment of the mousesatellite DNA explains its properties. The longest repeating unit of 234 bp is identified by the restriction digestion. The unit of reassociation between single strands of denatured satellite DNA is probably the 117-bp half-repeat, because the 234-bp fragments can anneal both in register and in half-register (in the latter case, the first half-repeat of one strand renatures with the second halfrepeat of the other).

So far, we have treated the present satellite as though it consisted of identical copies of the 234-bp repeating unit. Although this unit accounts for the majority of the satellite, variants of it also are present. Some of them are scattered randomly throughout the satellite, whereas others are clustered.

The existence of variants is implied by the description of the starting material for the sequence analysis as the “monomeric” fragment. When the satellite is digested by an enzyme that has one cleavage site in the 234-bp sequence, it also generates dimers, trimers, and tetramers relative to the 234-bp length. They arise when a repeating unit has lost the enzyme cleavage site as the result of mutation.

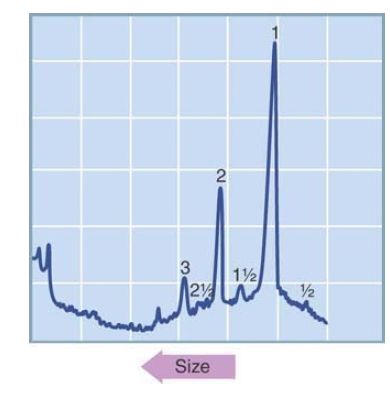

The monomeric 234-bp unit is generated when two adjacent repeats each have the recognition site. A dimer occurs when one unit has lost the site, a trimer is generated when two adjacent units have lost the site, and so on. With some restriction enzymes, most of the satellite is cleaved into a member of this repeating series, as shown in the example of FIGURE 5. The declining number of dimers, trimers, and so forth shows that there is a random distribution of the repeats in which the enzyme’s recognition site has been eliminated by mutation.

FIGURE 5 Digestion of mouse satellite DNA with the restriction enzyme EcoRII identifies a series of repeating units (1, 2, 3) that are multimers of 234 bp and also a minor series (½, 1½, 2½) that includes half-repeats (see accompanying text). The band at the far left is a fraction resistant to digestion.

Other restriction enzymes show a different type of behavior with the satellite DNA. They continue to generate the same series of bands. However, they digest only a small proportion of the DNA, say 5% to 10%. This implies that a certain region of the satellite contains a concentration of the repeating units with this particular restriction site. Presumably the series of repeats in this domain all are derived from an ancestral variant that possessed this recognition site (although some members since have lost it by mutation).

A satellite DNA suffers unequal recombination. This has additional consequences when there is internal repetition in the repeating unit. Let us return to our cluster consisting of “ab” repeats. Suppose that the “a” and “b” components of the repeating unit are themselves sufficiently similar to allow them to pair. Then, the two clusters can align in half-register, with the “a” sequence of one aligned with the “b” sequence of the other. How frequently this occurs depends on the similarity between the two halves of the repeating unit. In mouse satellite DNA, reassociation between the denatured satellite DNA strands in vitro commonly occurs in the half-register.

When a recombination event occurs out of register, it changes the length of the repeating units that are involved in the reaction:

xababababababababababababababababy

×

xababababababababababababababababy

↓

xabababababababababababababababababy

+

xababababababababbabababababababy

In the upper recombinant cluster, an “ab” unit has been replaced by an “aab” unit. In the lower cluster, an “ab” unit has been replaced by a “b” unit.

This type of event explains a feature of the restriction digest of mouse satellite DNA. Figure 5 shows a fainter series of bands at lengths of 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, and 3.5 repeating units, in addition to the stronger integral length repeats. Suppose that in the preceding example, “ab” represents the 234-bp repeat of mouse satellite DNA, generated by cleavage at a site in the “b” segment. The “a” and “b” segments correspond to the 117-bp half-repeats.

Then, in the upper recombinant cluster, the “aab” unit generates a fragment of 1.5 times the usual repeating length. In the lower recombinant cluster, the “b” unit generates a fragment of half of the usual length. (The multiple fragments in the half-repeat series are generated in the same way as longer fragments in the integral series, when some repeating units have lost the restriction site by mutation.)

Turning the argument around, the identification of the half-repeat series on the gel shows that the 234-bp repeating unit consists of two half-repeats closely related enough to pair sometimes for recombination. Also visible in Figure 6.17 are some rather faint bands corresponding to 0.25- and 0.75-spacings. These will be generated in the same way as the 0.5-spacings, when recombination occurs between clusters aligned in a quarterregister.

The decreased relationship between quarter-repeats compared with half-repeats explains the reduction in frequency of the 0.25- and 0.75-bands compared with the 0.5-bands.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)