النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 10-3-2016

Date: 7-3-2016

Date: 2-3-2016

|

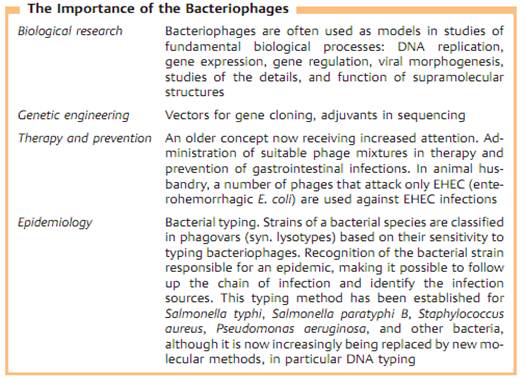

Bacteriophages

Introduction

Bacteriophages, or simply phages, are viruses that infect bacteria. They possess a protein shell surrounding the phage genome, which with few exceptions is composed of DNA. A bacteriophage attaches to specific receptors on its host bacteria and injects its genome through the cell wall. This forces the host cells to synthesize more bacteriophages. The host cell lyses at the end of this reproductive phase. So-called temperate bacteriophages lysogenize the host cells, whereby their genomes are integrated into the host cell chromosomes as the so-called prophage. The phage genes are inactive in this stage, although the prophase is duplicated synchronously with host cell proliferation. The transition from prophage status to the lytic cycle is termed spontaneous or artificial induction. Some genomes of temperate phages may carry genes which have the capacity to change the phenotype of the host cell. Integration of such a prophage into the chromosome is known as lysogenic conversion.

Definition

Bacteriophages are viruses the host cells of which are bacteria. Bacteriophages are therefore obligate cell parasites. They possess only one type of nucleic acid, either DNA or RNA, have no enzymatic systems for energy supply and are unable to synthesize proteins on their own.

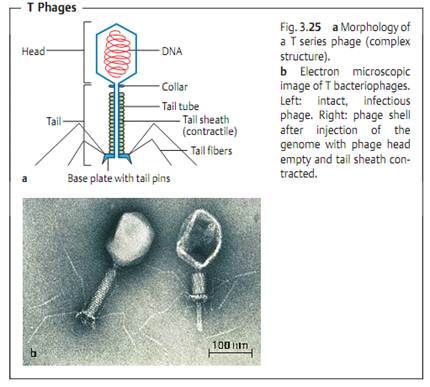

Morphology

Similarly to the viruses that infect animals, bacteriophages vary widely in ap-pearance. Fig. 3.25a shows a schematic view of a T series coli phage. Research on these phages has been particularly thorough. Fig. 3.25b shows an intact T phage next to a phage that has injected its genome.

Composition

Phages are made up of protein and nucleic acid. The proteins form the head, tail, and other morphological elements, the function of which is to protect the phage genome. This element bears the genetic information, the structural genes for the structural proteins as well as for other proteins (enzymes) required to produce new phage particles. The nucleic acid in most phages is DNA, which occurs as a single DNA double strand in, for example, T series phages. These phages are quite complex and have up to 100 different genes. In spherical and filamentous phages, the genome consists of single-stranded DNA (example: UX174). RNA phages are less common.

Reproduction

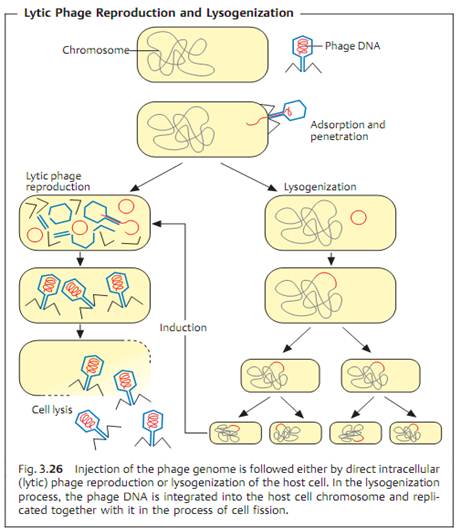

The phage reproduction process involves several steps (Fig. 3.26).

- Adsorption. Attachment to cell surface involving specific interactions between a phage protein at the end of the tail and a bacterial receptor.

- Penetration. Injection of the phage genome. Enzymatic penetration of the wall by the tail tube tip and injection of the nucleic acid through the tail tube.

- Reproduction. Beginning with synthesis of early proteins (zero to two minutes after injection), e.g., the phage-specific replicase that initiates replication of the phage genome. Then follows transcription of the late genes that code for the structural proteins of the head and tail. The new phage particles are assembled in a maturation process toward the end of the reproduction cycle.

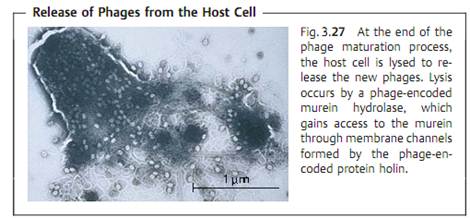

- Release. This step usually follows the lysis of the host cell with the help of murein hydrolase coded by a phage gene that destroys the cell wall (Fig. 3.27).

Depending on the phage species and milieu conditions, a phage reproduction cycle takes from 20 to 60 minutes. This is called the latency period, and can be considered as analogous to the generation time of bacteria. Depending on the phage species, an infected cell releases from 20 to several hundred new phages, which number defines the burst size. Thus phages reproduce more rapidly than bacteria. In view of this fact, one might wonder how any bacteria have survived in nature at all. It is important not to forget that cell population density is a major factor determining the probability of finding a host cell in the first place and that such densities are relatively small in nature. Another aspect is that only a small proportion of phages reproduce solely by means of these lytic or vegetative processes. Most are temperate phages that lysogenize the infected host cells.

Lysogeny

Fig. 3.26 illustrates the lysogeny of a host cell. Following injection of the phage genome, it is integrated into the chromosome by means of region-specific recombination employing an integrase. The phage genome thus integrated is called a prophage. The prophage is capable of changing to the vegetative state, either spontaneously or in response to induction by physical or chemical noxae (UV light, mitomycin). The process begins with excision of the phage genome out of the DNA of the host cell, continues with replication of the phage DNA and synthesis of phage structure proteins, and finally ends with host cell lysis. Cells carrying a prophage are called lysogenic because they contain the genetic information for lysis. Lysogeny has advantages for both sides. It prevents immediate host cell lysis, but also ensures that the phage genome replicates concurrently with host cell reproduction.

Lysogenic conversion is when the phage genome lysogenizing a cell bears a gene (or several genes) that codes for bacterial rather than viral processes. Genes localized on phage genomes include the gene for diphtheria toxin, the gene for the pyrogenic toxins of group A streptococci and the cholera toxin gene.

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|