تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء والفلسفة

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

The scalar product

المؤلف:

Richard Fitzpatrick

المصدر:

Classical Electromagnetism

الجزء والصفحة:

p 10

2-1-2017

1956

The scalar product

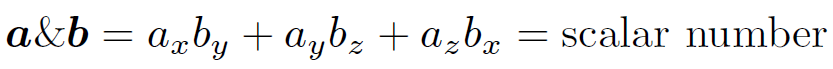

A scalar quantity is invariant under all possible rotational transformations. The individual components of a vector are not scalars because they change under transformation. Can we form a scalar out of some combination of the components of one, or more, vectors? Suppose that we were to define the ''ampersand" product

(1.1)

(1.1)

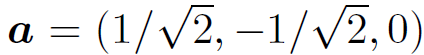

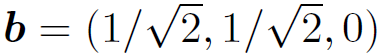

for general vectors a and b. Is a&b invariant under transformation, as must be the case if it is a scalar number? Let us consider an example. Suppose that a = (1, 0, 0) and b = (0, 1, 0). It is easily seen that a&b = 1. Let us now rotate the basis through 45o about the z-axis. In the new basis,  and

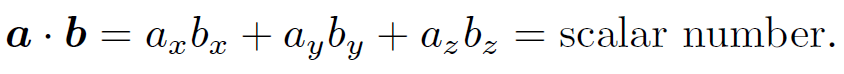

and  , giving a&b = 1=2. Clearly, a&b is not invariant under rotational transformation, so the above definition is a bad one. Consider, now, the dot product or scalar product:

, giving a&b = 1=2. Clearly, a&b is not invariant under rotational transformation, so the above definition is a bad one. Consider, now, the dot product or scalar product:

(1.2)

(1.2)

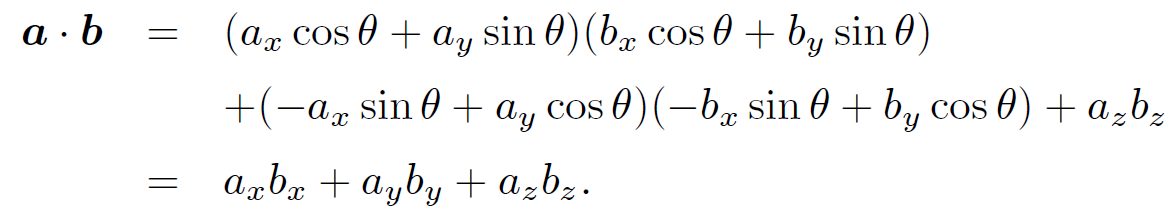

Let us rotate the basis though µ degrees about the z-axis. According in the new basis a . b takes the form

(1.3)

(1.3)

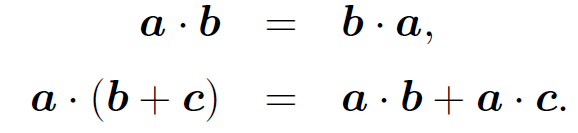

Thus, a . b is invariant under rotation about the z-axis. It can easily be shown that it is also invariant under rotation about the x- and y-axes. Clearly, a . b is a true scalar, so the above definition is a good one. Incidentally, a . b is the only simple combination of the components of two vectors which transforms like a scalar. It is easily shown that the dot product is commutative and distributive:

(1.4)

(1.4)

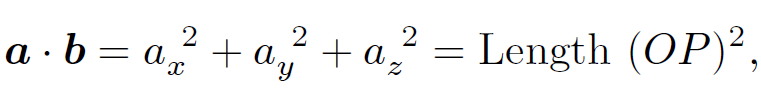

The associative property is meaningless for the dot product because we cannot have (a . b) . c since a . b is scalar. We have shown that the dot product a . b is coordinate independent. But what is the physical significance of this? Consider the special case where a = b. Clearly,

(1.5)

(1.5)

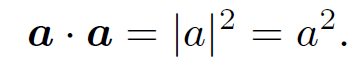

if a is the position vector of P relative to the origin O. So, the invariance of a . a is equivalent to the invariance of the length, or magnitude, of vector a under transformation. The length of vector a is usually denoted |a| (''the modulus of a") or sometimes just a, so

(1.6)

(1.6)

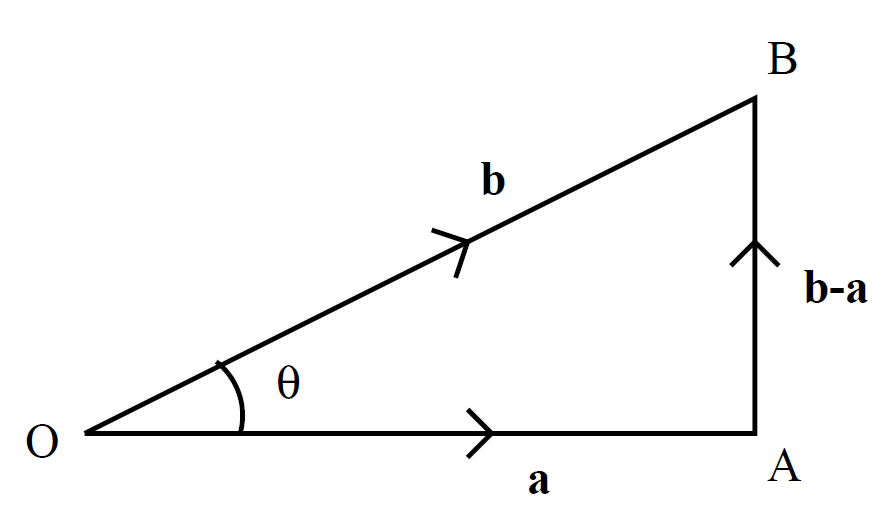

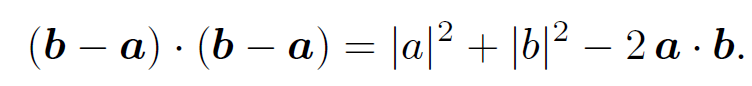

Let us now investigate the general case. The length squared of AB is

(1.7)

(1.7)

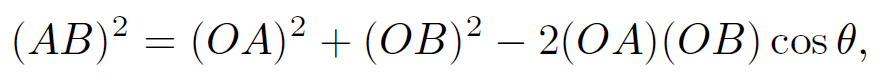

However, according to the ''cosine rule" of trigonometry

(1.8)

(1.8)

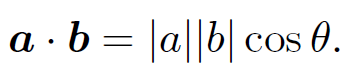

where (AB) denotes the length of side AB. It follows that

(1.9)

(1.9)

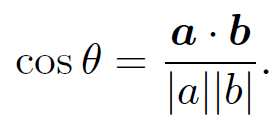

Clearly, the invariance of a . b under transformation is equivalent to the invariance of the angle subtended between the two vectors. Note that if a. b = 0 then either |a| = 0, |b| = 0, or the vectors a and b are perpendicular. The angle subtended between two vectors can easily be obtained from the dot product:

(1.10)

(1.10)

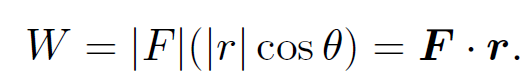

The work W performed by a force F moving through a displacement r is the product of the magnitude of F times the displacement in the direction of F. If the angle subtended between F and r is θ then

(1.11)

(1.11)

The rate of flow of liquid of constant velocity v through a loop of vector area S is the product of the magnitude of the area times the component of the velocity perpendicular to the loop. Thus,

Rate of flow = v . S. (1.12)

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الرياضية

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الرياضية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)