Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-08-23

Date: 2023-11-29

Date: 2023-04-12

|

An outline of the semantic structure of the class of Dyirbal verbs, with full semantic descriptions of about 250 members of the class, is in Dixon 1968 a. We discuss criteria for semantic grouping within the verb class, and give semantic descriptions of a small sample of verbs.

Dyirbal verbs fall, on syntactic and semantic grounds, into seven sets (the sixth of which is a residue set):

(1) Verbs of position, including ‘go’, ‘sit’, ‘lead’, ‘take’, ‘throw’, ‘pick up’, ‘ hold ’, ‘ empty out ’, and so on.

(2) Verbs of affect, including ‘pierce’, ‘hit’, ‘rub’, ‘burn’, and so on.

(3) Verbs of giving.

(4) Verbs of attention: ‘look’, ‘listen’, ‘take no notice’.

(5) Verbs of speaking and gesturing: ‘tell’, ‘ask’, ‘call’, ‘sing’, and so on.

(6) Verbs dealing with other bodily activities; a residue set including ‘cry’, ‘ laugh ’, ‘ blow ’, ‘ copulate ’, ‘ cough ’, and so on.

(7) Verbs of breaking, that are ‘meta’ with respect to verbs in other sets, and can also have specific meanings: ‘ break ’, ‘ fall ’, ‘ peel ’.

Each set (except the sixth) is semantically homogeneous; that is, a collection of semantic systems, arranged in a single dependency tree, serves to generate the componential descriptions of nuclear members of the set.

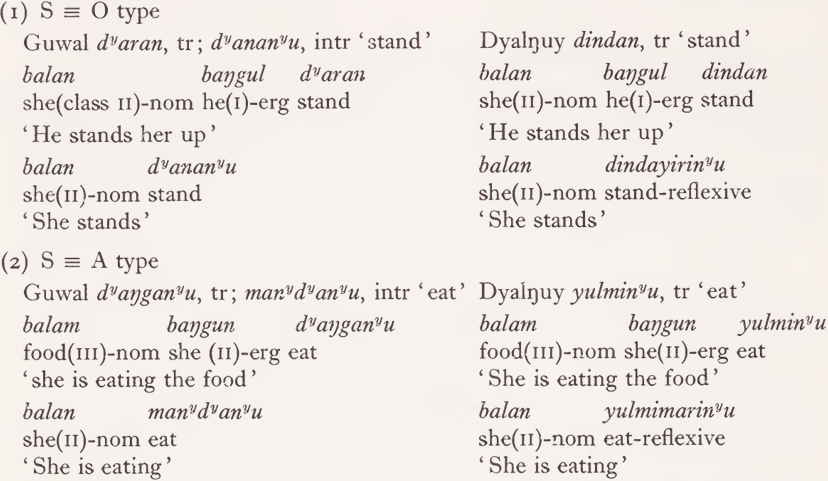

A syntactic criterion, setting off set 1 from the other sets, concerns the identification of syntactic function between transitive and intransitive sentences. We will use A, O and S as abbreviations for the functions ‘subject of transitive verb’, ‘ object of transitive verb ’, ‘ subject of intransitive verb ’ respectively. Now verbs in some sets (2, 3, 4) are all1 transitive. In other sets both transitive and intransitive verbs occur; a transitive verb in a mixed transitivity subset is often related to an intransitive verb (in the same subset) by having the same semantic content, and differing only in transitivity. Such transitive verbs are of two distinct types according as, when an intransitive verb and a transitive verb with the same semantic content describe the same event, the realization of the subject of the intransitive verb coincides with:

(1) the realization of the object of the transitive verb (the case S =0)

or

(2) the realization of the subject of the transitive verb (the case S = A).

Further, the subject of the reflexive form of a transitive verb of type (1) is equivalent to the object of the original transitive form; and for a verb of type (2), to the transitive subject.

Dyalŋuy data demonstrates the types S = O and S = A. In almost every case Dyalŋuy has just one transitive verb where Guwal has a transitive-and-intransitive pair; the reflexive form of the Dyalŋuy verb is given as correspondent of the Guwal intransitive verb. Examples are:

Other S = O pairs include take out/come out (he takes her out/she comes out), waken (he wakens her/she wakens); S = A pairs include follow (he follows her/he follows), tell/talk (he tells her/he talks).

Another syntactic correlation concerns ‘ accompanitive forms ’; any intransitive verb can be made into an ‘accompanitive form’ by adding affix -m(b)al; it then has the syntactic possibilities of a transitive verb. The accompanitive form of an intransitive verb that has the same semantic content as a transitive verb of type S = A is syntactically and semantically equivalent to the transitive verb; this is not so for type S = O verbs. Thus corresponding to balan manydyanyu ‘ she is eating ’ we have accompanitive balam baŋgun manydyayman ‘she is eating food’ which could be realized by the same event as balam baŋgun dyaŋganyu; manydyayman and dyaŋganyu appear to be exact synonyms.2 However, the accompanitive form of balan dyananyu ‘ she is standing ’ would be a construction with the ‘ woman ’ NP in the ergative case, say bala baŋgun dyanayman ‘ she is standing with it (e.g. a stick in her hand)’, whereas for the transitive equivalent of dyananyu the ‘woman’ NP must be in nominative case: balan baŋgul dyaran ‘ he is standing her up (if she is a child that cannot stand well, say, or a sick woman) ’.

All transitive verbs, except verbs of giving, occur in reflexive form and thus can be typed as S = A or S = O from consideration of the syntax of the reflexive, even if they do not belong to a transitive/intransitive pair.

Verbs in set 1 are all of type S = O. Verbs in sets 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 are of type S = A. Verbs in set 3 cannot be categorized as either type. There is an apparent exception, a transitive/intransitive pair ‘follow’ that is concerned with motion (and thus should be in set 1) but is of type S = A. This pair is best regarded as the converse (Lyons 1963.72) of the S = O pair ‘lead/go’ - thus we have she goes/he leads her/ she follows him / she follows. The relation ‘converse’ involves interchange of subject and object functions.. The ‘follow’ pair are thus basically (i.e. in deep representation) of type S = O, like other verbs.

Verbs of ‘position’ clearly fall into two selectional sets: verbs of motion that can only occur with ‘to’ or ‘from’ qualifiers, and verbs of rest that are restricted to ‘at’ qualification. The selection is so strong that it justifies including an appropriate semantic feature - ‘motion’ or ‘rest’ - in the description of each nuclear verb of position. Verbs in other sets can, in plausible situational circumstances, receive unmarked ‘rest’ qualification (e.g. hit/laugh/give at the camp), but cannot occur with ‘to’ or ‘from’ verb markers. (Appendix 2 discusses some exceptions to this: verbs of seeing.) All this suggests that a verb marker accompanying a position verb should be within the VP whereas one accompanying a verb not concerned with position should be outside the VP.

Set 1 is thus syntactically set off from the other sets by (1) including all and only verbs of type S = O, (2) its members strongly selecting either ‘motion’ or ‘rest’ verb markers.

The first subset of set 1 can be called ‘simple motion’.3 The componential descriptions all include the feature ‘motion’; they continue with ‘here’ or ‘there’ (with unmarked ‘to’) for baninyu ‘come’, yanu ‘go’; or with ‘not water’ plus ‘down’ or ‘up’, or ‘water’ plus ‘down’ or ‘up’ or ‘across’ for the specialized verbs of motion. ‘Transitive’ or ‘intransitive’ must be added to complete a semantic description. Most verbs of simple motion are intransitive but there is, for instance, dangan ‘river or flood washes something away’, the transitive correspondent of intransitive dadanyu ‘motion downriver’ (and their Dyalŋuy correspondents are balbulumban, balbulubin respectively). The very general verb waymbanyu ‘go walkabout’ can be given semantic description just (position, motion; intr); dyadyan ‘hop’-which has the same Dyalŋuy correspondent, dyurbarinyu, as waymbanyu - is defined in terms of waymbanyu and the selection of a subject that is a member of the kangaroo genus.

The next subset, ‘simple rest’, includes a number of transitive and intransitive verbs with the feature ‘rest’, and then ‘sit’, ‘stand’ or ‘lie’. We then have verbs dealing with position where immersion in water is involved. Since we have already had cause to set up the system (water, NOT WATER) this can be exploited here: we can assign semantic description (position, water; intr) to the very general verb ŋabanyu ‘bathe’ and descriptions (position, water, motion; intr) and (position, water, rest; intr) to yuŋaranyu ‘swim’ and walŋan ‘float’, the ‘water’ equivalents of waymbanyu ‘go walkabout’ and nyinanyu ‘stay’ respectively. The inclusion of the feature ‘water’ in the componential descriptions of these three verbs implies the inclusion of ‘NOT WATER’ for verbs of simple motion and simple rest. However in this and other cases we can shorten statements of semantic description by omitting UNMARKED features (such as ‘NOT WATER');4 the fact that there is a verb with semantic description (position, water, motion; intr) indicates that waymbanyu, stated as (position, motion; intr), implicitly involves the feature ‘NOT WATER’.

A componential semantic description is generated from a dependency tree of systems, such as that on page 447; one feature is chosen from the topmost system, one feature from the system depending on that choice, and so on, until some node at the bottom of the tree is reached. The features in a componential description are ordered according to their positions in the dependency tree. Thus wandin is (position, motion, water, up; intr). The importance of the ordering can be seen if we compare wandin with yuŋaranyu, description (position, water, motion; intr).5 The place of ‘water’ in the ordered string of features is vital: by the conventions which arc used here ‘water’ following ‘motion’ implies motion with respect to water (hence wandin, ‘motion upriver’), whereas ‘water’ following ‘position’ implies position in water (hence yuŋaranyu, ‘swim’).6

Set 1 also includes subsets of ‘induced motion’ and ‘induced rest’. For instance, ‘carry’ and ‘pull’ relate to induced motion, whereas ‘lead’ does not involve any inducing. Induced motion can be regarded as the intersection of features ‘affect’ and ‘motion’. It can be of two types ‘induced change of position’ and ‘induced state of motion’: the difference is dealt with through the system (place, direction) already needed for the grammatical description. Similarly, induced rest involves ‘affect’ and ‘rest’.

Of the ‘induced change of position’ verbs, gundan ‘put in’ is (position, affect, motion, place, interior, to; tr); its complement buŋgan ‘empty out’ has ‘from’ in place of ‘to’, budin ‘take or bring by carrying in hand’ and dimbanyu ‘carry, not with the hand - e.g. carry a dilly-bag with the strap across one’s forehead, wear a hat, wear a feather loincloth’ have features ‘person’, ‘hand’ and ‘person’, ‘not hand’ respectively, in addition to ‘position’, ‘affect’, ‘motion', ‘place’. Complements yilmbun ‘ pull, drag ’ and digun ‘ clear away, rake away, dig - using hands - on the surface ’ require ‘ here ’, ‘ to ’ and ‘ here ’, ‘ from ’ respectively in addition to ‘ position ’, ‘affect’, ‘motion’ and ‘place’.

There are four main ‘ induced state of motion ’ verbs. The general verbs, transitive duman ‘shake’ and intransitive gawurinyu ‘move generally, e.g. toss and turn, fidget, “just going along”’,7 whose descriptions involve just ‘position’, ‘affect’, ‘motion’, ‘direction’. And the more specific madan ‘throw’ and baygun ‘shake, wave or bash’ that also involve ‘let go of’ and ‘hold on to’ respectively.

The main ‘induced state of rest’ verb is nyiman ‘catch hold of’ with description (position, affect, rest, person; tr). There are also verbs that appear to be nuclear and which combine the notions of induced rest and induced motion: maŋgan ‘ pick up ’ can be described as ‘ induced motion in order to be in an induced state of rest (relative to a person) ’ where the in order to be is the purposive construction of Dyirbal grammar (see Dixon 1968 a). Cases like this suggest that the hypothesis of this paper - nuclear equals componential, non-nuclear equals definitional description-is an oversimplification. Another complexity-for which no provision was made is the undoubtedly nuclear verb banaganyu ‘return’ whose semantic description involves (position, motion; intr) and also reference to some place that the subject was at rest at before beginning a series of interconnected actions that he has just completed; banaganyu has a wide range of meaning and can imply return to the place left a few seconds ago, or to the camp left three days ago.

Set 2, of affect verbs, are all of type S = A, on the evidence of reflexives, and are neutral with respect to locational qualification. Unlike set 1, which includes a good number of intransitive verbs, set 2 verbs are all transitive (the single exception - bundalanyu ‘fight’-is probably a fossilized reciprocal form and requires plural subject). The actions realising verbs from set 2 induce a ‘state’ in the object, that can be described by a (normally non-cognate) adjective - this is the main property distinguishing these verbs from those of other sets.

Members of the first subset include feature ‘affect’ and also ‘strike’; there is then specification of ‘rounded object’, ‘long rigid object’ (this choice requires an obligatory further choice from the system (let go of, hold on to}), ‘long flexible object’, ‘sharp pointed implement’ (for verbs ‘pierce’, ‘spear’, etc.) or ‘sharp bladed implement’ (for ‘cut’, ‘scrape’, etc.). Other verbs in set 2 involve features ‘rub’, ‘wrap/tie’, ‘fill in’, ‘cover’, ‘burn’.

There are several stages to making a hut, and a special verb describes each in Guwal:

(1) gadan ‘build up the frame by sticking posts into the ground’ - this is a non¬ nuclear verb defined in terms of nuclear bagan ‘pierce’, description (affect, strike, sharp pointed implement; tr).

(2) bardyan ‘tie the posts together with loya vine, making the frame firm’, defined in terms of non-nuclear dyunin ‘tie together, make tight’, which is itself defined in terms of nuclear dyaguman ‘tie up, wrap up’, description (affect, wrap; tr).

(3) wamban ‘fill in between the frame with leaves, bark or grass, taking especial care to make the bottom snakeproof’, defined in terms of nuclear guban, (affect, cover; tr).

Now in Dyalŋuy there is one holophrastic verb that covers all three stages, i.e. that refers to the complete complex action of building a hut; Dyalŋuy wurwanyu is the correspondent of Guwal gadan, bardyan and wamban. Normally a Dyalŋuy verb corresponds to a Guwal nuclear verb and a number of related Guwal non¬nuclear verbs; here wurwanyu refers to three non-nuclear verbs each of which is related to a different nuclear verb (and each of the three nuclear verbs has its own Dyalquy correspondent). This is the only instance in the writer’s data of a holophrastic verb of this type occurring in Dyalŋuy.

Set 3 includes nuclear wugan ‘give’ and seven non-nuclear items. Semantically these are derived from the syntactic dummy poss that in the grammar underlies possessive constructions (although poss itself is not realized as a ‘ surface verb ’ in Dyirbal; instead it triggers off an ‘ affix transfer ’ transformation and is then deleted - for details see Dixon, 1969).

Set 4, verbs of attention, involves first a choice from the system (take notice, take no notice}. Nuclear verb midyun ‘take no notice of, ignore’ has description (attention, take no notice; tr); the reflexive form of midyun carries the meaning ‘wait’. Feature ‘take notice’ involves a further choice, from system (seen, unseen (but heard)}: nuclear verbs buɽan ‘see, look at’ and ŋamban ‘hear, listen to’. The reflexive of ŋamban can be translated ‘think’ (lit. ‘hear oneself’).

Verbs in set 5 refer to language activity. There are six main nuclear verbs, buwanyu ‘tell’, ŋanban ‘ask’, ŋayban ‘call, by voice or gesture’, bayan ‘sing’, and the complements gigan ‘ tell to do, let do ’ and dyabin' stop someone doing something ’; the reflexive of dyabin bears the meaning ‘ refuse ’. ŋaɽin ‘ answer ’ is a non-nuclear verb defined in terms of gayban ‘ call ’ - literally ‘ call in turn ’.

Verbs which do not fall into any of the other sets are grouped together in set 6. These verbs have no common semantic feature, but they do appear to have a vague overall resemblance - they are all concerned with ‘bodily activity’ (other than seeing, hearing and speaking): ‘eating’, ‘kissing’, ‘laughing’, ‘coughing’ and so on. These verbs deal with particularly human physiological activities, so that we would be unlikely to find any exactly corresponding verbs in non-human languages; the semantic features required for the other verb sets, however, might well recur (albeit in different dependencies, and so on) in the semantic description of a ‘ language’ spoken by non-human aliens. Set 6 includes the only Dyirbal intransitive verbs that are not semantically related (as synonyms, near-synonyms or antonyms, leaving aside differences of transitivity) to some transitive verbs.

Verbs in set 7 refer to the ‘ breaking off’ of some state or action; they are thus in a sense ‘meta’ with respect to verbs in other sets. If gaynydyan occurs in a VP with verb X it means ‘the action referred to by X was broken off, i.e. stopped’; in a VP by itself the unmarked realization of gaynydyan is ‘ something - e,g. a branch - breaks’. A feature ‘break off’ can be set up, that can occur in a semantic description together with either ‘motion’ or ‘rest’; gaynydyan is thus (break off, rest; intr). ‘Break off’ plus ‘motion’, without any further specification, implies ‘fall down’ (nuclear badyinyu); with specification ‘ down on the ground ’ it implies ‘ be bogged (in mud) ’ (non-nuclear bumanyu). There is a single Dyalŋuy verb, dagaranyu, corresponding to Guwal gaynydyan, badyinyu and bumanyu, supporting the description of these words as all involving feature ‘break off’. dagaranyu is also the correspondent for Guwal verbs ganydyan ‘ take all the peel off, take clothes off, take a necklace off, etc.’, ginbin ‘ peel off just the top layer of skin (from a fruit) ’ and dyinin ‘ break a shell (of an egg or nut) ’.

The semantic descriptions of some words may appear surprising to speakers of English. Thus ‘ come out ’ might be thought to involve simple motion, rather than induced motion, and to have as complement ‘ go in ’. In Dyirbal, nuclear gundan ‘ put in ’ (and gundabin ‘ go in ’) has as complement buŋgan ‘ empty out ’; bundin ‘ take out ’ and mayin ‘come out’ are non-nuclear verbs defined in terms of nuclear yilmbun ‘ pull, drag ’ (that has as complement digun ‘ clear away, rake away ’); all these verbs involve induced motion. Dyalŋuy gives evidence for these groupings, which are examples of the mildly different ‘ world view ’ of the Dyirbal.

Each of the nuclear verbs mentioned in the brief survey above (but for a very few items, such as miyandanyu ‘ laugh ’) has associated non-nuclear verbs that are semantically defined in terms of the nuclear verb. As examples of the types of further specification that non-nuclear items may provide for a single nuclear verb, we give below three nuclear verbs and their associated non-nuclear verbs. These examples have been chosen to involve only straightforward definitions, avoiding complexities and indeterminacies. Parentheses round a word refer to the semantic description of that word.

(1) Nuclear maŋgan ‘pick up’; semantic description (position, affect, motion, place; tr) joined by the purposive grammatical construction ‘in order to’ with (position, affect, rest, person; tr). Non-nuclear naŋginyu ‘scrap about - e.g. on floor, in dish or in dilly-bag - picking up crumbs’; defined as (maŋgan) plus affix -dyay ‘ repeat event many times within short time-span Non-nuclear dyaŋinyu ‘ mock, i.e, imitate a person’s voice and words ’; defined as (naŋginyu) plus specification of guwal ‘ language ’ in object function to the verb. There is also non-nuclear dyaymban ‘ find ’, the intersection of (maŋgan) and (buɽan) ‘ look ’.

(2) Nuclear bidyin ‘hit with a rounded object, e.g. punch with fist, hit with a thrown stone, a woman banging a skin drum stretched across her knees, a car crashing into a bank, heavy rain falling’; semantic description (affect, strike, rounded object; tr). Non-nuclear dyilwan ‘kick, or shove with knee’; defined as (bidyin) with specification of dyina ‘foot’ or buŋgu ‘knee’ in transitive subject/instrument function to the verb. Non-nuclear dudan ‘ mash [food] with a stone ’; defined as (bidyin) plus specification of either diban ‘stone’ as subject and/or wudyu ‘food’ as object. Non-nuclear dalinyu ‘ deliver a blow to someone lying down, e.g. fall on someone ’ involves the intersection of (bidyin) and (badyinyu), i.e. (break off, motion; intr).

(3) Nuclear buɽan ‘see, look at’; semantic description (attention, take notice, seen; tr). Non-nuclear waban ‘ look up at5; defined as (buɽan) plus ‘ up ’, as in bound form -gala (see n.b, p. 443). barmin ‘ look back at ’; (buɽan) plus ‘ behind ’, as in bound form - ŋaru (see n« b, p. 443). walginyu ‘ look over or round [something] at [something else], e.g. look at someone hiding somewhere, look at a baby inside a cradle, look round a tree at, look out through a window at ’; (buɽan) plus X with locative inflection and the further affix -ru ‘motion’, where X is a noun referring to any object - i.e. ‘ look round an object ’. ɽuyginyu ‘ look in at, e.g. look in through a window at, open a suitcase and look inside’; (buɽan) plus ‘interior’, ‘to’, ɽugan ‘ look on at, i.e. watch someone going out in front ’; (buɽan) plus specification of the object as moving (by a relative clause involving the unmarked verb yanu ‘go’) and/or plus ‘out in front’, bound form galu (see n. b, p, 443). wamin look at someone, without the person being aware that he is being watched ’; (buɽan) with subject X and object Y, together with (gulu buɽan) -gulu is the operator ‘ not ’ - with subject Y and object X. ŋaɽnydyanyu ‘stare at’; (buɽan) plus qualifier dyunguru ‘ strongly ’. gindan ‘ look with the aid of artificial light [at night] ’; (buɽan) with specification of nyaɽa ‘ light’ as part of the subject/instrument NP. yaŋan ‘ look over land for something, e.g. look for good water hole, or for forked stick for house frame, or look at water to see if there are any fish in it ’ - note that the object of yaŋan will be the place that is looked at, whereas for buɽan it is most frequently the thing that is looked for; (buɽan) with object some ‘place’, joined by the purposive construction ‘ in order to ’ with (buɽan) with object ‘ some needed object ’. ŋuŋgan ‘ look at something from the past, e.g. go back and search for something that was found before but left for later, or look at a tree, say, and recognize it’; (buɽan) plus specification of the object ‘ from past time ’.

Detailed Dyalŋuy correspondences support these and other definitions - details are in Dixon 1968 a.

Nothing in this paper should be taken as definitive. Exploratory account of a method of semantic description; further work is likely to reveal it to be grossly oversimplified. Similarly, the descriptions of Dyirbal verbs are in most cases only tentative, and require further checking in the field, as well as more detailed assessment for theoretical consistency and sufficiency. There are points of similarity with recent work on generative grammar - particularly Fillmore (1968) and unpublished work of Lakoff, McCawley, Postal and Ross. It would be instructive to develop further some of the ideas in this paper on the basis of this work; this has not been attempted here.

I have tried in this paper to stick fairly closely to semantic descriptions suggested by mother-in-law language data, and not to extrapolate or generalize too far beyond this. Further work would have to range more widely and more deeply - for instance, nuclearity may be a rather ‘ deep ’ notion, and each nuclear ‘ concept ’ need not necessarily have a simple surface representation, as has been implied here.

A next step would be to attempt to apply the method of semantic description outlined here to other languages. Explanatory investigations of English verbs from this point of view have proved encouraging (see Dixon, forthcoming, b).

1 The few exceptions are intransitive roots that are obviously historically derived from transitive roots - a fossilized reflexive in set 4 and one fossilized reciprocal in each of sets 2 and 3.

2 We are deliberately oversimplifying here, since there is in fact a slight difference in seman¬ tic content for the ‘ eat ’ pair. manydyanyu is ‘ eat fruit or vegetables to appease hunger ’ while dyaŋganyu is ‘ eat fruit or vegetables (whether or not particularly hungry) ’; there is a different verb, intransitive ɽubinyu, for the eating of fish or meat. However, for all the other pairs mentioned here transitive and intransitive members have exactly the same semantic content.

3 The notes that follow mention only some of the nuclear verbs in each set.

4 The notion of semantic markedness could be developed further (beyond the tentative comments in the present paper) along lines similar to Chomsky and Halle’s discussion of phonological markedness, in chapter 9 of The sound pattern of English (1968).

5 Here a single system - {water, not water} - occurs twice, at different positions, in the dependency tree.

6 These two semantic descriptions also differ in that zvandin involves ‘ up ’. The description of Dyirbal does not yield a true minimal pair - two semantic descriptions involving the same features, differing only in feature ordering; however, such a minimal pair is likely to be encountered as this method of semantic description is applied more widely.

7 gazvurinyu can refer to any sort of induced state of motion, of anything. Consider the sentence bayindvana gingin, mala guludyilu baygul, gazvurimban bagu mayagu guralmali (he- nom-emphatic dirty-nom, hand-nom not-emphatic he-ergative, move-accompanitive-pres/ past it-dat ear-dat clean-causative-purposive) ‘he’s certainly got a dirty [ear], and can’t even [be bothered to] lift (gazvurinyu) [his] hand to clean [his] ear’.

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|