Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-12

Date: 2023-08-12

Date: 2024-02-06

|

The polysemy of -ize derivatives

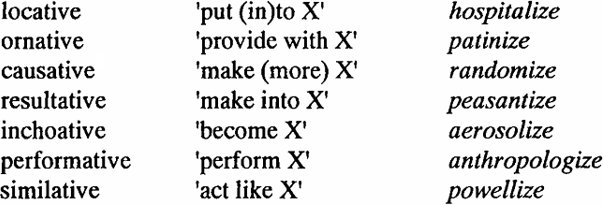

As a first step in the analysis, the data in the corpus were classified according to the set of semantic categories given in (1), which more or less include all of the paraphrases and meanings mentioned so far.1 The left column gives the name of the category, the second contains a paraphrase, and the third provides an example from the corpus. I will use the names of the categories as convenient mnemonic terms for some of the semantic representations to be introduced.

(1)

causative 2

As mentioned already in the introduction, explicit accounts of the relationship between these categories are non-existent. I will show that each of the seven categories can be subsumed under a single LCS, which the reader can find below. For expository purposes, however, I will go through the different meanings successively and develop the unitary LCS step by step.

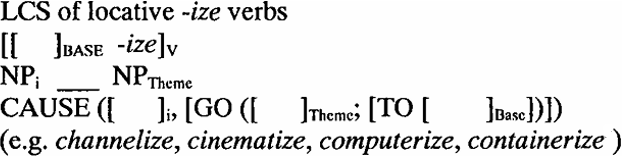

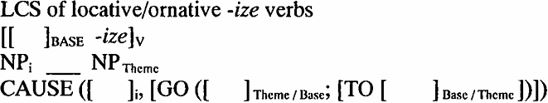

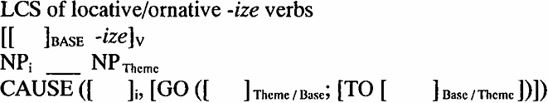

Let us first look at locative uses of -ize, for which I propose the following LCS:

(2)

containerize 3

In non-technical terms the structure in (2) reads as follows. Locative verbs involving the base [ ]Base and the suffix -ize are transitive and denote an Event in which the subject causes the transfer of what is denoted by the object NP to the entity that is denoted by the base. An example from the corpus is containerize 'pack into containers' which, according to (2), must be interpreted as in (3), given a sentence like The men containerized the cargo.

(3)

(3) could be read as "the men caused a transfer of the cargo into a container or containers".

This example possibly raises the question whether the locative function TO should not be represented by a more specific function, e.g. IN. From a lexicographic point of view, this would certainly yield a more adequate interpretation of containerize. However, we are not primarily concerned here with the accurate lexicographic representation of individual lexemes, but with the fundamental morphological problem how complex words are semantically related to other complex words, and how stems and affixes in complex words interact with one another. In other words, no semantic de scription of a morphological process can even hope to give a lexicographically precise description of all possible or attested derivatives, but can only aim at capturing regularities that predict the range of possible meanings of possible derivatives. This means that we are dealing with semantic structures that are necessarily underspecified.

Coming back to the derivative containerize, the LCS in (2) can therefore only tell us that, in informal terms, someone puts something somewhere, and that, in the case of containerize, 'somewhere' is denoted by the base container. With containerize, speakers will interpret TO as 'into', in other cases other interpretations are possible. In the notation used here, TO is thus considered an underspecified locative function.

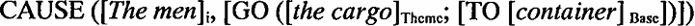

Having illustrated the LCS of locatives, we may turn to ornatives like patinize4, for which I propose the following LCS (given a sentence like They patinized the zinc articles, a modified version of the original OED quotation):

(4)

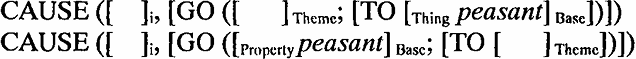

Thus ornatives denote the transfer of the referent of the base word to the referent of the object NP, which is exactly the reverse of what we observed with locatives.5 The LCS of ornatives may be represented as in (5):

(5)

A comparison of the LCSs of locatives and ornatives brings to the fore the close semantic relationship between the two categories: only the arguments of the GO function are exchanged in (2) and (5). In other words, it is the occurrence of the arguments in the different slots which makes the verb ornative or locative, respectively. The two LCSs can therefore be united in a - now polysemous - LCS, given in (6):

(6)

(6) expresses the fact that it is either the referent of the base that is transferred to the referent of the object or the other way round. How do speakers know which argument goes into which slot? In the default case, one of the two interpretations will be ruled out on the basis of our encyclopaedic knowledge. Thus one knows that it is usually the patients that are transferred to the hospital and not the hospital brought to the patients. If we imagine a world where the latter would be the case, this event could be easily referred to by the verb hospitalize. Thus, the LCS in (6) is in principle ambiguous between an ornative and a locative meaning. One can therefore suspect that there be cases where it is impossible to assign a clearly locative or clearly ornative meaning. And this is exactly what we find in the corpus.

Consider, for example, channelize, which can mean 'put into a channel or channels', which is the locative interpretation. Channelize can, however, also mean 'to provide with channels' as illustrated by the quotation given in the OED, in which channelize is paraphrased as 'to control traffic by curbs and dividers'. Another example is computerize which cannot only mean 'put (data) into the computer', which is locative, but also 'to install a computer or computers in (an office, etc.)' (OED), which is ornative.

Coming back to the initial examples containerize and patinize, let us briefly consider the alternative interpretations, given in (7a) and (7b):

(7)

These interpretations, though structurally possible, are again ruled out on the basis of the meaning of the base word and world knowledge. A patina is a Ά film or incrustation ... on the surface of old bronze ... or other substances' (OED). A patina is therefore something that cannot exist without the object whose surface it covers. Hence, it must be the patina that is brought onto the object's surface and not the object that is attached to the patina. Similarly, it is the cargo which is placed inside the container and not the container which is placed around the cargo. The examples illustrate that it is unnecessary to provide a more restrictive LCS since unwarranted interpretations are ruled out on the basis of independent semantic or conceptual knowledge.

The underspecified LCS structure does therefore not only account for the differences in interpretation between different derivatives, but can also explain putative and actual polysemies of individual derivatives. This is an important point because in earlier approaches the polysemy of individual derivatives is mostly ignored. Previous authors seem to have tacitly assumed that each derivative can only express one of the many possible meanings -ize words can express.

Let us turn to the causative meaning, which is closely related to the locative/ornative case. The crucial difference between these two categories is that the transfer denoted by the function GO is not of a physical nature with causatives. Whether we are dealing with a physical or a non-physical transfer depends on the semantic interpretation of the arguments of the GO function. While with spatial locatives/ornatives the arguments [ ]Base and [ ]Theme belong to the semantic category Thing, the respective arguments in the LCS of causatives are Properties. This is expressed in (8) below by the subscript "Thing, Property" in the empty argument slots of the GO and TO functions. In more traditional terms locatives/ornatives can be characterized as change-of-place verbs, whereas causatives are change-of-state verbs. In the unified LCS, the nature of the arguments is not fixed, but is projected by the arguments themselves. I therefore propose to extend the LCS for locatives/ornatives, given in (2) above, to causatives:

(8)

It could be argued that Jackendoffs functions INCH and BE (AT) (roughly 'become') are better suited for the expression of change-of-states than GO. As already mentioned in note 10 above, this option would also be available for the locative and ornative meanings. Jackendoff argues for INCH, and against GO, with verbs of touching and attachment (a class that roughly corresponds to my locatives and ornatives) because "there are no alternative paths available for verbs of attachment [and touching, I.P.], nor can anything be said about intermediate steps in the process of attachment [or touching, LP.]" (1990:114). Especially the argument concerning intermediate steps is compelling with the simplex verbs Jackendoff discusses, but in the case of -ize derivatives it loses its force, because these words often make reference to intermediate steps. It is a well-known fact that causatives (and inchoatives, discussed below) often do not mean 'make something X' but 'make something more X'. A nice example of this kind is the linguistic term grammaticalize, which is standardly used in the sense of 'make or become more grammatical'. Under the INCH analysis, such an interpretation would be impossible because we cannot refer to intermediate steps. Jackendoff discusses this problem with respect to the two causative verbs yellow and cool. While he finds the case of yellow equivocal, he prefers the function GO for the semantic description of cool because only GO can express a change over time without necessarily achieving a certain state. Hence, he paraphrases cool as 'continuously change temperature towards the direction of coolness' (1990:95).

Returning to the discussion of -ize derivatives, parallel arguments apply. GO is superior in expressing the semantics of these derivatives because it allows both readings, the 'contact' reading with ornatives, locatives, and many causatives ('achievement' in Jackendoffs terms), as well as the 'intermediate step' reading with certain causatives ('change over time in a certain direction' in Jackendoffs terms). The same holds for inchoatives.

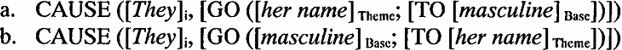

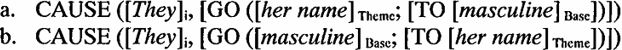

Let us now illustrate the workings of (8) with the derivative masculinize 'render (more) masculine' in a sentence like They masculinized her name (again modeled on the OED quotation):

(9)

In (9a) GO is the function expressing the change-of-state of the argument [her name]Theme, which can be paraphrased as something like 'They rendered her name (more) masculine'. (9b) is also permitted by the given LCS, and differs from (9a) in that [masculine]Base is imposed on the argument [her name]Theme· Hence, (8) predicts that there are two possible, slightly differing interpretations of the verb masculinize, formally expressed as (9a) and (9b), respectively. This prediction is borne out by the facts, since, in addition to the meaning (9a) 'render masculine', the interpretation (9b) is also listed in the OED ('Biol. To induce male characteristics in'). In other words, the LCS in (8) does not only predict the canonical meaning of causative derivatives standardly cited as 'make, render X', but also the less prominent, but equally possible, meaning 'induce X in'.

But not only the causative meaning itself is ambiguous, one also finds some derivatives in the corpus that can be interpreted both in the locative/ornative and in the causative sense. Take, for example, nuclearize, which is attested with the meanings 'To supply or equip (a nation) with nuclear weapons' (OED) and 'To render (a family, etc.) nuclear in character' (OED). In the first case the base word is interpreted as a Property 'Of, pertaining to, possessing, or employing nuclear weapons' (one of the meanings of nuclear in the OED). With the second meaning of nuclearize the base is interpreted as the Property 'Having the character or position of a nucleus; like a nucleus; constituting or forming a nucleus', which is another meaning of nuclear given by the OED. Spelling out the semantic categories of the relevant arguments of GO, the LCS looks as follows:

(10)

Another example of this kind of ambiguity is publicize whose LCS predicts again two interpretations:

(11)

(11a) either denotes that something is made public (the Property reading), or the transfer to the public (the Thing reading). Both interpretations of (11a) are given by the OED ('to make generally known', '[t]o bring to the notice of the public'). In the first case traditional analyses would claim that the base is adjectival, in the second case nominal. The analysis along the lines of (8) and (11a) makes reference to the syntactic category of the base unnecessary, and arguments about whether a derivative is deadjectival or denominal appear futile. (11b) illustrates the ornative variant, of which only the first alternative (inducing a Property) is in accordance with the extra-linguistic world, i.e. it is the news that is brought to the public rather than the public to the news.

The derivative publicize thus illustrates two important points. First, arguments about the exact categorization of the semantic nature of the derivative (locative, ornative or causative?) are fruitless, if they fail to recognize the identical structures that unite locative, ornative and causative -ize verbs. Second, we have seen that the syntactic category of the base is irrelevant. In standard treatments locative and ornative -ize derivatives are regarded as denominal, while causatives have adjectival bases. Based on these generalizations, different denominal and deadjectival word formation rules have been proposed. While the observations concerning the syntactic category of the bases are not entirely wrong, it seems that the specification of the syntactic category of the base is an unnecessary complication which leads to empirical and theoretical problems. In a purely semantic approach, the syntactic category of the base can be disregarded because the only restriction necessary is that the base can succesfully be interpreted as an appropriate argument in the LCS.

However, if the syntactic category of the base is not specified, why can only adjectives and nouns, and not verbs, serve as bases of -ize derivatives? As was just mentioned, possible bases must be able to be interpreted as appropriate arguments in the LCS. In the above LCSs possible arguments of GO and TO in the LCS of -ize verbs are restricted to Things and Properties. Arguments as projected by verbs, i.e. Events, Actions or States, are therefore excluded. Note that this restriction is also expressed in Lieber's LCSs, where the open argument slots are equally reserved for Things and Properties. Given that this argument specification is independently needed, our analysis has the advantage that the restriction to nominal and adjectival bases falls out automatically, making the specification of the syntactic category of the base redundant.

Let us turn to the category 'resultative', which is usually depicted as the denominal counterpart of the deadjectival causative (cf. e.g. the treatment in Rainer 1993:238-239). However, the distinction between 'make X' and 'make into X' seems to be conceptually unmotivated and can be characterized as an artefact of an inappropriate meta-language that treats paraphrases as if they were direct representations of meaning. In our framework, the resultative and the causative collapse into one category. Take, for example, the meaning of peasantize 'to make (oneself) into a peasant' (OED), where the base is interpreted either as a Property induced in the object NPTheme, or as a kind of person into which NPTheme is transformed.

(12)

Why does peasantize not mean 'supply with peasants' (ornative interpretation), or 'make someone go to a peasant' (locative)? First of all, the spatial-ornative meaning is not attested but is certainly possible. A village, for example, could be peasantized by making more peasants live there. This type of meaning is actually attested with two derivatives out of the large group of forms that relate to a country or group of people, e.g. Anglicanize, Baskonize, Cubanize, Czechize, Mongolianize, Nigerianize, Scandinavianize, Turkicize, Vietnamize. While most of these derivatives only show the causative meaning 'render X in character', the resultative meaning 'turn into an X' is also attested. The said ornative forms are Romanianize and Filipinize 'supply with Romanians/Filipinos' (cf. the quotations in the OED), which is exactly parallel to the putative ornative formation peasantize (a village).

But why is the locative interpretation apparently ruled out? Generalizing from the previous examples it seems that the semantic-categorial interpretation of the arguments largely depends on the inherent semantics of these arguments. Thus certain nouns like hospital or ghetto are prone to spatial-locative interpretations, while nouns denoting persons never seem to adopt this meaning. The reason for this is not obvious, but it seems that with verbs like hospitalize non-locative interpretations are indeed possible. Thus, if hospitalized was not lexicalized with its spatial-locative meaning, it is conceivable that the conversion of an institution (say, a child-care center) into a hospital (i.e. a change-of-state) could be referred to with the verb hospitalize. The inherent semantics of hospital, in which the 'location' meaning is more prominent than the 'institution' meaning, strongly favors the locative interpretation.6 A similar reasoning holds for the non-attested, but possible interpretation of locatives like containerize as causatives/resultatives 'make (into) a container'. Coming back to the problem of peasantize, the interpretation of peasant as a location could be ruled out along the same lines, since the semantic information concerning the Property is more prominent than the possibility of being a location. However, the latter interpretation would not be excluded on structural grounds, nor is it obvious that it should be. Consider the derivative Vietnamize, which was cited above as belonging to the same group as, for example, Cubanize. The interesting point with Vietnamize is that its attested meaning is not the causative but the locative 'make something go to Vietnam', in the sense of 'handing over to the state of Vietnam'. Compare the quotation from the OED:

(13) 1969 Daily Tel. 25 Oct. 5/3: It was learned .. that America had handed over another base to South Vietnam. Two of the United States major port facilities, including the one in Saigon, were next on the list to be 'Vietnamized'.

To summarize, it is unclear whether any account of -ize derivatives should include principled mechanisms that would strictly prevent items like peasantize from being interpreted as a locative derivative, and how such a mechanism would still allow the correct interpretation of items like Vietnamize. We will leave this issue to further research.

Coming back to the difference between the resultative and causative categories we have seen that the only formal difference lies in the syntactic category of the base (N vs. A) and in the paraphrase ('make X' vs. 'make into X'). Both differences are naturally accounted for under the analysis proposed here. Reference to the syntactic category of the base is superfluous, and the difference in the paraphrase does not have a correlate in the semantics but merely shows that paraphrases of this kind are not an appropriate meta-language.

Consider another example, fantasize, of which one reviewer says that it is not adequately described by the proposed model. According to the LCSs above, this derivative could be analyzed as a causative/resultative formation in the sense of 'making (into) a fantasy'. The reviewer quotes the COBUILD dictionary's definition of fantasize to show that the above LCSs cannot capture the "rich meaning" of fantasize: "If you fantasize, you think about a pleasant event or situation which you would like to happen but which is unlikely to happen." (COBUILD:515). However, one should not equate dictionary definitions with semantic structures. Thus, the dictionary gives three definitions of the base word fantasy, one of which is almost entirely identical with the definition of the derivative fantasize: "a pleasant situation or event that you think about and hope will happen, although it is unlikely to happen" (COBUILD:516). This meaning of fantasy seems to be derived from the more general meaning "a story or situation that someone creates from their imagination and that is not based on reality". From these definitions of the base word and the LCS above, the meaning of fantasize can be predicted rather precisely as a straightforward causative/resultative, 'making (into) a fantasy'. The rest follows from the "rich meaning" of the base word.

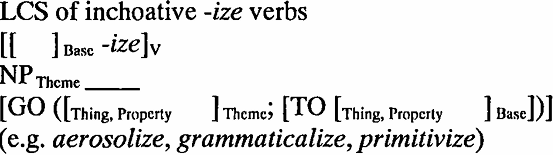

Having shown that resultatives can also be subsumed under the LCS (13), we may turn to the discussion of inchoatives. The label 'inchoative' is usually attached to derived verbs that are intransitively used and whose meaning can be paraphrased as 'become X'. In the corpus of neologisms this meaning is not very frequent, but it seems that most transitive derivatives expressing a change-of-state can potentially also be used intransitively. I propose the following LCS for inchoatives:

(14)

The difference between the LCSs in (9) and (14) is that the latter lacks the function CAUSE, and that - consequently - the Agent argument of CAUSE is also lacking. Finally, the Theme occurs in the surface subject position and not in the object position. The LCSs of the previously discussed derivatives and the inchoative ones are unified in (15):

(15)

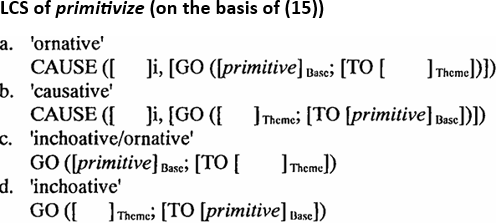

Following the arguments and conventions presented in Jackendoff (1990:73), the dashed underline signals that the CAUSE function is optional. If it is applied, we are dealing with the locative/ornative/causative/resultative meanings discussed above, if it is not, we are confronted with an inchoative meaning. Before we turn to the problem of the syntactic realization of the Theme as the subject in inchoative structures, let us first illustrate (15) with an example from the corpus for which both transitive and intransitive variants are attested. Primitivize is characterized by the OED as 'trans, and intr. To render primitive; to impute primitiveness to; to simplify; to return to an earlier stage'. The possible LCSs look as follows, with the mnemonic categorization given at the end of each line:

(16)

(16a) formalizes the meaning 'impute primitiveness to', (16b) spells out as 'render primitive', and (16d) 'become primitive' corresponds to the OED's 'to return to an earlier stage'. The interpretation (16c) would be dispreferred with the base primitive, because the transfer of a Property to a Thing usually requires an Agent, i.e. the CAUSE function. A structure like (16c) should, however, not be ruled out a priori as a possible structure. In the case of oxidize the structural parallel to (16c) is entirely appropriate, because of the inherent semantics of the base:

(17)

The meanings as given by the OED for intransitive oxidize match exactly the ones described by (17). Thus, interpretation (17a) is a formalization of the OED's 'become coated with oxide', and (17b) corresponds to 'become converted into an oxide'. The reason for the adequacy of (17a) is that the base can be interpreted as a Thing that is transferred to [ ]Theme without visible instigation. Such an interpretation is less likely with (16c). The examples show again how the correct interpretations can be construed on the basis of the general LCS of -ize verbs in interaction with the inherent semantics of the arguments involved.

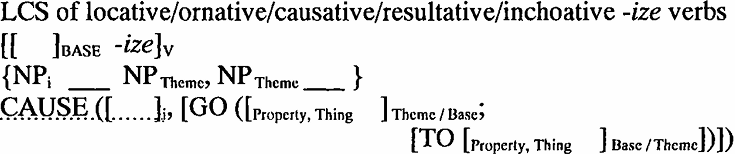

Let us turn to the problem of subjecthood. In the LCS (15) it is left unclear how, when and why the Theme should appear in subject position. Two solutions to this problem are possible, a local, i.e. lexical one and a more general one.

The lexical solution would mean that the object/subject alternation is encoded in the LCS itself, i.e. some device in the LCS regulates that in the case of the non-presence of NP¡, ΝΡTheme occurs in the subject position. A LCS of this kind could take the following form:

(18)

According to (18), -ize verbs may occur either transitively, i.e. in the syntactic frame [NP¡ ΝΡ Theme], or intransitively, i.e. in the frame [NP Theme ]. In those cases where the underlined function is lacking, the second frame applies automatically.

Although this lexical solution works properly for -ize verbs, there are strong arguments in favor of a more principled solution. Such arguments are based on the observation that the subject/object alternation of Theme arguments is not restricted to a particular class of derived verbs but a rather wide-spread phenomenon. A standard example is the verb open, whose Theme may appear as the subject of the intransitive form or as the object of the transitive form. A number of principled analyses of such mismatches between syntactic and conceptual relations have been proposed (see Jackendoff 1990:155ff for an overview), an evaluation of which is beyond the scope of this investigation. Since the problems of a principled analysis are still hotly debated, I will adopt the more conservative lexical solution here. Future research will show how the proposed lexical mechanisms can be eliminated in favor of more general principles (see Jackendoff 1990: chapter 11 for some suggestions). In any case, the decision on this problem does not substantially affect the proposed analysis of -ize verbs.

Another problem concerns the optionality of the CAUSE function in the LCS (15). The formulation of (15) suggests that any -ize verb may be used as an inchoative, which is certainly not the case. Locative and ornative derivatives necessarily take three arguments, and a putative intransitive form hospitalize can therefore only be interpreted as 'become a hospital'.

Since inchoatives lack an overt instigator one can expect intransitive forms typically with Events where Agency is either unclear or unnecessary to specify. This prediction is borne out by the data. Consider for example aerosolize, which in its intransitive form denotes a process that is governed by the laws of physics (cf. the quotation given by the OED "Six per cent, of the total amount of penicillin aerosolized").

So far, our treatment may have suggested that intransitive derivatives are automatically interpreted as inchoatives. This is, however, not true. In some cases we find intransitive forms that do not correspond to the analysis of inchoative derivatives as put forward above. This group of non-inchoative intransitive -ize derivatives is the one that was labeled 'performatives' in (1), and whose meaning can be paraphrased as 'perform X', e.g. anthropologize, or apologize (Lieber's example, not a 20th century neologism). Let us consider in some detail the intransitive form anthropologize 'intr. to pursue anthropology' (OED) as in John anthropologized in the field (a slightly modified OED quotation). In such cases, the Theme argument remains unexpressed, while there is a clear Agent expressed by the subject NP (in this case [John]). This suggests that there is yet another syntactic frame for -ize verbs, namely [NP¡____]. Incorporating this frame into (18) yields the following LCS:

(19)

The LCS of John anthropologized (in the field) looks then as in (25):

(20)

Given the lack of an overt object, only two syntactic structures can be mapped onto the semantic representation, namely [NP Theme [NP¡ ____ ]. Thus [John] can be either interpreted as [NP¡ ], yielding the interpretation (20a), or as [NP Theme ____ ], with the interpretation (20b). (20a) can be paraphrased as 'John applied anthropology to an unmentioned object', while (20b) would paraphrase as 'John became anthropology', which is an interpretation that can be ruled out on pragmatic grounds. Thus the introduction of a third syntactic frame naturally solves the syntactic and semantic problems with the group of derivatives called 'performatives' above, which can, like the other groups, be subsumed under the LCS (19).

I have already critically mentioned Lieber's example economize, which, although not a 20th century innovation, would nicely fit into the performative group (instead of Lieber's 'manner' group (5d)). One of the meanings of the base word economy, and surely the pertinent one in this case, is given by the OED as 'Frugality, thrift, saving'. Accordingly, and correctly I think, the intransitive derivative economize is defined by the OED 'To practise economy', which parallels our analysis of verbs like apologize or anthropologize. Under Lieber's approach these similarities are not ackowledged and apologize and economize are taken as examples of different, even homophonous categories. As already pointed out, another disadvantage of Lieber's model is that the transitive use of performative -ize derivatives is left unexplained, whereas the present model predicts that transitive use is in principle possible.7

We may now turn to the last cluster of derivatives, called 'similatives', which are often paraphrased as 'act like X', 'imitate X', and which seem like an entirely separate class of derivatives, mostly with proper nouns as their bases. Lieber's analysis of these forms as in (5d) is therefore not at all far-fetched. However, both the traditional paraphrases and Lieber's LCS (5d) cannot cope with the problem that most, if not all of the pertinent derivatives are transitive. I will show that these formations can be subsumed under the general LCS of -ize derivatives. The corpus contains the following forms, among others: Coslettize, Hooverize, Lukanize, Maoize, Mandelize, Marxize, Powellize, Stalinize, Sherardize, Taylorize. Let us examine how they fit into the LCS of -ize verbs by looking briefly at the form Marxize, as in The socialists Marxize the West (adopted under slight modification from an OED quotation), and the form Taylorize. For reasons of space and clarity only the transitive forms will be considered; the analysis of intransitives can be done in a parallel fashion (see the discussion above):

(21)

Two interpretations are structurally possible. The first is that [Marx] is induced in [the West], the second is that [the West] is transferred to [Marx]. Both interpretations only make sense if the base Marx is not interpreted as the name of a person but metonymically as a framework of ideas. Such cases of metonymy are a rather frequent phenomenon, which can be illustrated by a sentence like

(22) Marx is rather out-dated these days.

The referent of Marx in (22) is not Marx himself, but his ideas, usually referred to by the form Marxism. Reference to metonymie meanings is also attested in other areas of word-formation, e.g. with the suffix -(i)an. A Chomskian may have nothing to do with Chomsky himself, but follows the master's ideas. Coming back to the structures in (21), we can paraphrase them as either 'the socialists induce Marxism in the West' or 'the socialists make the West adopt Marxism'.

Let us briefly discuss the second example, Taylorize, which is paraphrased by the OED as 'To introduce the Taylor system into'. In other words, we are confronted with an ornative meaning where the base Taylor stands metonymically for the system invented by Taylor (similar arguments apply with the other derivatives mentioned). In sum, the oft-cited meaning 'act like X, imitate X' (formally encapsulated in Lieber's LCS (5d)) is the result of the inference that if one applies the ideas or manners of a certain person, one acts like that person.8

As was already pointed out above, previous approaches have difficulties in explaining the transitive use of similative derivatives. However, analyzing similatives as special kinds of ornatives, as suggested above, can nicely account for this fact. Furthermore, the proposed analysis explicates the relationship between the similative and the other interpretations of -ize verbs. If there were no such relationship, as suggested by the advocates of the homonymy position, the very existence of a similative interpretation would be totally unwarranted.

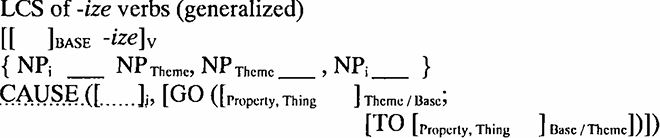

To summarize the discussion of each of the semantic categories mentioned in (6), we can say that all of them are derived from a single LCS, which I repeat here for convenience:

(23)

This LCS can account for the vast majority of 20th century neologisms in -ize. In the remainder, I want to discuss the very few derivatives in the corpus that seem to be impossible to interpret on the basis of the proposed LCS. These derivatives are prisonize ' To cause (a person) to adapt himself to prison life', weatherize 'To make weatherproof, winterize 'To adapt or prepare (something) for operation or use in cold weather', ecize 'of plants: to become established in a new habitat', and cannibalize 'To take parts from one unit for incorporation in, and completion of, another (of a similar kind)' (all definitions OED).

In the case of cannibalize, the derivative has only a remote semantic relationship to the base word's meaning. Without the appropriate context, or knowledge of the lexicalized form, the correct meaning cannot be inferred. Cannibalize may well have been coined in analogy to derivatives with a similative meaning 'act like a cannibal', but, if so, it is unclear, why it does not mean 'eat someone of your own species'. In other words, cannibalize is semantically not transparent and has only a very remote relationship to productively formed -ize derivatives.

Not quite as remote seems to be the relationship between regular -ize words and the forms prisonize, weatherize and winterize. Although these forms cannot be interpreted in terms of (23), they do denote the inducing of a property in the Thing denoted by Theme. However, this property is not denoted by the base. Rather these forms could be paraphrased as 'adapt something to X', with X being the base word. These deviant forms seem to be based on the inference that adaptation always implies a change of Properties. As shown by van Marie (1988), such inferences are not uncommon and often lead to the development of a greater semantic diversity of a derivational category. Hence, the three forms can be regarded as being derived by a creative extension of the original semantics of regular -ize formations.

Turning to the derivative ecize, it is clear from the quotation given in the OED that this form has been intentionally coined by biologists on the basis of ecesis (cf. Greek  'to colonize'), apparently in analogy to other nouns in -sis (e.g. hypothesis, metathesis) which in their majority may undergo -ize suffixation (e.g. Raffelsiefen 1996). In general, the words of this type show the kind of polysemy discussed in connection with the LCS in (23). Thus, ecize (like e.g. metamorphosize and metathesize) belongs to the performative group, while others may be considered resultatives or locatives (e.g. hypothesize, not a 20th century neologism), or ornatives (e.g. metastasize) etc. Semantically, ecize is thus a regular formation.

'to colonize'), apparently in analogy to other nouns in -sis (e.g. hypothesis, metathesis) which in their majority may undergo -ize suffixation (e.g. Raffelsiefen 1996). In general, the words of this type show the kind of polysemy discussed in connection with the LCS in (23). Thus, ecize (like e.g. metamorphosize and metathesize) belongs to the performative group, while others may be considered resultatives or locatives (e.g. hypothesize, not a 20th century neologism), or ornatives (e.g. metastasize) etc. Semantically, ecize is thus a regular formation.

In sum, even the putatively idiosyncratic formations can be shown to be at least remotely related to the general semantics of -ize. Given that idiosyncratic, lexicalized meanings are a rather common phenomenon with derivational categories, these isolated exceptions do not challenge our overall analysis. Quite to the contrary, the fact that they are so small in number supports the semantic coherence of -ize derivatives as expressed by the LCS in (23).

An additional argument for the suggested analysis comes from the relative stability of -ize affixation over the centuries and from its present productivity. Van Marie (1988) argues that semantically diverse morphological processes tend to lose their productivity, unless their diversity is still transparently related. The latter is crucially the case with all processes that display polysemy proper, like, for example, Dutch subject nouns (Booij 1986). The fact that -ize is definitely a productive verb-deriving process in English is another indication that we are dealing with a semantically transparent, polysemous process.

Lieber (1996) questions the semantic transparency of -ize derivatives and calls this suffix only 'partially determinate'. She claims that it is more determinate than, for example, Ν to V conversion, but less determinate than the formation of denominal verbs in de- (such as debug, deflea, dethrone). This view rests on two questionable assumptions. The first is that "the more transparent the meaning, the more productive the pattern of word formation" (1996:10). While a significant relationship between semantic transparency and productivity cannot be denied, it seems that this relationship is not of the kind assumed by Lieber. Thus, there are completely unproductive derivational processes in English that are nevertheless semantically highly transparent (e.g. nominal -th, verbal -en). However, there seems to be no process that is semantically non-transparent and nevertheless productive. These considerations boil down to the more moderate and more accurate generalization that productive processes are always transparent.

Based on her questionable assumption, Lieber then puts forward that the greater productivity of denominal de- is an indication of the fact that -ize is semantically less determinate than de-. First of all, it can seriously be doubted that de- is in fact more productive than -ize. Unfortunately, Lieber does not give any source for her "recent calculation of Ρ for de- ... P=0.0465" (as against P=0.0072 for denominal -ize and 0.0138 for deadjectival -ize), but if CELEX was used, the figures cannot be trusted. My own calculation on the basis of the OED (again 20th century neologisms) yields a different result. Including denominal, deverbal, and parasynthetic formations with de-, I arrived at 115 types, which is less than half the number of -ize neologisms in this source.9

Secondly, it is unclear what, if anything, such purely quantitative assesssments of productivtiy can tell us about the semantics of a morphological process, since even unproductive processes can be transparent. Thus, even if de- had a higher Ρ than -ize, this could be simply due to non-semantic (e.g. phonological or morphological) restrictions that constrain -ize formations but not de- formations. Attempts to base semantic conclusions on a simple comparison of purely quantitative measures are therefore totally unconvincing.

In sum, Lieber's arguments against the semantic coherence of -ize derivatives are not compelling.

1 Lieber's representations, for example, roughly correspond to the categories locative, ornative, causative, resultative, inchoative, and similative. See Rainer (1993:235-241) for a similar classification of Spanish derived verbs.

2 Traditionally, 'factitive' is used to refer to the induction of a property or properties in an object, whereas 'causative' is used for the incitement of an event. Hence Rainer (1993: 235, 238) employs the term 'factitive' for deadjectival formations, and the term 'causative' for denominal ones. In the morphological literature, these two concepts are often not distinguished. For reasons that will become clear below, the necessity of such a distinction for the description of derived verbs is indeed doubtful, and we will therefore use 'causative' as the cover term. Note, however, that nothing hinges on this decision since the terms used in (6) do not have any independent theoretical status in our model.

3 Note that some of these forms are polysemous themselves, i.e. they also have other, non-locative, interpretations. We will return to this issue below.

4 Patinize is the first derivative from the corpus which involves stem allomorphy. In general, stem allomorphy is rather common with -ize. However, cases of allomorphy can be straightforwardly accounted for by a number of morpho-phonological constraints without making reference to se mantic properties of the base or the derivative. For the purposes of the semantic analysis, we can therefore ignore stem allomorphy.

5 Note that in Jackendoffs (1990) system, verbs of attachment and covering would require a structure involving the functions INCH and BE (AT). For the present problem this difference can be ignored, since both locative and ornative meanings could equally well be formulated using these functions. We will re turn to this issue below.

6 Furthermore, the putting of patients into a hospital is culturally more salient than the conversion of hospitals into other institutions. Given the importance of frequency for lexicalization in general, it is this salience that is responsible for the lexicalization of the locative meaning of hospitalize.

7 That is not to say that all of the performative verbs must have a transitive variant. Examples like apologize show that this is not the case. Note, however, that one can apologize for something, in which case the normally unexpressed Theme surfaces syntactically as an adjunct phrase.

8 Sometimes such inferences contribute to a complete loss of productivity of a given rule. Van Marie (1988) is a detailed study of semantic diversity leading to the downfall of a morphological category.

9 A quantitative analysis of de- in the Cobuild corpus was not carried out.

|

|

|

|

خطر خفي في أكياس الشاي يمكن أن يضر صحتك على المدى البعيد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ماذا نعرف عن الطائرة الأميركية المحطمة CRJ-700؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الأمين العام للعتبة العلوية المقدسة يستقبل المتولّي الشرعي للعتبة الرضوية المطهّرة والوفد المرافق له

|

|

|