Motion

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 5

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 5

2024-01-27

2024-01-27

1449

1449

It has been emphasized earlier that physics, as do all the sciences, depends on observation. One might also say that the development of the physical sciences to their present form has depended to a large extent on the emphasis which has been placed on the making of quantitative observations. Only with quantitative observations can one arrive at quantitative relationships, which are the heart of physics.

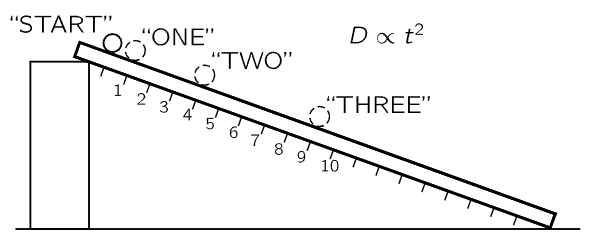

Many people would like to place the beginnings of physics with the work done 350 years ago by Galileo, and to call him the first physicist. Until that time, the study of motion had been a philosophical one based on arguments that could be thought up in one’s head. Most of the arguments had been presented by Aristotle and other Greek philosophers, and were taken as “proven.” Galileo was skeptical, and did an experiment on motion which was essentially this: He allowed a ball to roll down an inclined trough and observed the motion. He did not, however, just look; he measured how far the ball went in how long a time.

The way to measure a distance was well known long before Galileo, but there were no accurate ways of measuring time, particularly short times. Although he later devised more satisfactory clocks (though not like the ones we know), Galileo’s first experiments on motion were done by using his pulse to count off equal intervals of time. Let us do the same.

We may count off beats of a pulse as the ball rolls down the track: “one … two … three … four … five … six … seven … eight …” We ask a friend to make a small mark at the location of the ball at each count; we can then measure the distance the ball travelled from the point of release in one, or two, or three, etc., equal intervals of time. Galileo expressed the result of his observations in this way: if the location of the ball is marked at 1, 2, 3, 4, … units of time from the instant of its release, those marks are distant from the starting point in proportion to the numbers 1, 4, 9, 16, … Today we would say the distance is proportional to the square of the time:

D∝t2.

Fig. 5–1. A ball rolls down an inclined track.

The study of motion, which is basic to all of physics, treats with the questions: where? and when?

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة