تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Cavendish’s experiment

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 7

2024-02-04

1520

Fig. 7–13. A simplified diagram of the apparatus used by Cavendish to verify the law of universal gravitation for small objects and to measure the gravitational constant G.

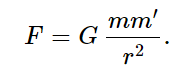

Gravitation, therefore, extends over enormous distances. But if there is a force between any pair of objects, we ought to be able to measure the force between our own objects. Instead of having to watch the stars go around each other, why can we not take a ball of lead and a marble and watch the marble go toward the ball of lead? The difficulty of this experiment when done in such a simple manner is the very weakness or delicacy of the force. It must be done with extreme care, which means covering the apparatus to keep the air out, making sure it is not electrically charged, and so on; then the force can be measured. It was first measured by Cavendish with an apparatus which is schematically indicated in Fig. 7–13. This first demonstrated the direct force between two large, fixed balls of lead and two smaller balls of lead on the ends of an arm supported by a very fine fiber, called a torsion fiber. By measuring how much the fiber gets twisted, one can measure the strength of the force, verify that it is inversely proportional to the square of the distance, and determine how strong it is. Thus, one may accurately determine the coefficient G in the formula

All the masses and distances are known. You say, “We knew it already for the earth.” Yes, but we did not know the mass of the earth. By knowing G from this experiment and by knowing how strongly the earth attracts, we can indirectly learn how great is the mass of the earth! This experiment has been called “weighing the earth” by some people, and it can be used to determine the coefficient G of the gravity law. This is the only way in which the mass of the earth can be determined. G turns out to be

6.670×10−11 newton⋅m2/kg2.

It is hard to exaggerate the importance of the effect on the history of science produced by this great success of the theory of gravitation. Compare the confusion, the lack of confidence, the incomplete knowledge that prevailed in the earlier ages, when there were endless debates and paradoxes, with the clarity and simplicity of this law—this fact that all the moons and planets and stars have such a simple rule to govern them, and further that man could understand it and deduce how the planets should move! This is the reason for the success of the sciences in following years, for it gave hope that the other phenomena of the world might also have such beautifully simple laws.

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)