Series and parallel impedances

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 25

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 25

2024-03-14

2024-03-14

1869

1869

Finally, there is an important item which is not quite in the nature of review. This has to do with an electrical circuit in which there is more than one circuit element. For example, when we have an inductor, a resistor, and a capacitor connected as in Fig. 24–2, we note that all the charge went through every one of the three, so that the current in such a singly connected thing is the same at all points along the wire. Since the current is the same in each one, the voltage across R is IR, the voltage across L is L(dI/dt), and so on. So, the total voltage drop is the sum of these, and this leads to Eq. (25.15). Using complex numbers, we found that we could solve the equation for the steady-state motion in response to a sinusoidal force. We thus found that  . Now

. Now  is called the impedance of this particular circuit. It tells us that if we apply a sinusoidal voltage,

is called the impedance of this particular circuit. It tells us that if we apply a sinusoidal voltage,  , we get a current

, we get a current  .

.

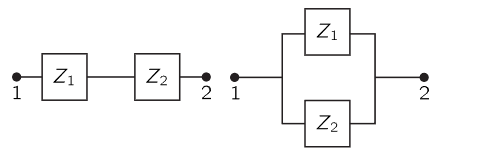

Fig. 25–6. Two impedances, connected in series and in parallel.

Now suppose we have a more complicated circuit which has two pieces, which by themselves have certain impedances,  and

and  and we put them in series (Fig. 25–6a) and apply a voltage. What happens? It is now a little more complicated, but if

and we put them in series (Fig. 25–6a) and apply a voltage. What happens? It is now a little more complicated, but if  is the current through

is the current through  , the voltage difference across

, the voltage difference across  ,

,  ; similarly, the voltage across

; similarly, the voltage across  is

is  The same current goes through both. Therefore the total voltage is the sum of the voltages across the two sections and is equal to

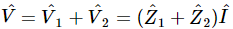

The same current goes through both. Therefore the total voltage is the sum of the voltages across the two sections and is equal to  . This means that the voltage on the complete circuit can be written

. This means that the voltage on the complete circuit can be written  where the

where the  of the combined system in series is the sum of the two

of the combined system in series is the sum of the two  of the separate pieces:

of the separate pieces:

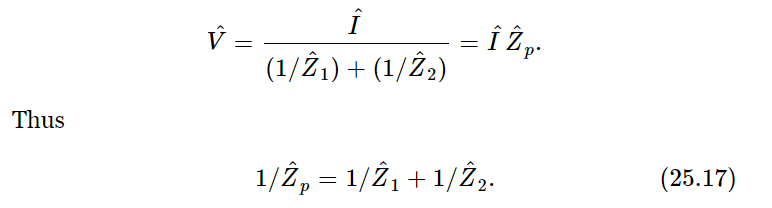

This is not the only way things may be connected. We may also connect them in another way, called a parallel connection (Fig. 25–6b). Now we see that a given voltage across the terminals, if the connecting wires are perfect conductors, is effectively applied to both of the impedances, and will cause currents in each independently. Therefore the current through  is equal to

is equal to  The current in

The current in  is

is  It is the same voltage. Now the total current which is supplied to the terminals is the sum of the currents in the two sections:

It is the same voltage. Now the total current which is supplied to the terminals is the sum of the currents in the two sections:  This can be written as

This can be written as

More complicated circuits can sometimes be simplified by taking pieces of them, working out the succession of impedances of the pieces, and combining the circuit together step by step, using the above rules. If we have any kind of circuit with many impedances connected in all kinds of ways, and if we include the voltages in the form of little generators having no impedance (when we pass charge through it, the generator adds a voltage V), then the following principles apply: (1) At any junction, the sum of the currents into a junction is zero. That is, all the current which comes in must come back out. (2) If we carry a charge around any loop, and back to where it started, the net work done is zero. These rules are called Kirchhoff’s laws for electrical circuits. Their systematic application to complicated circuits often simplifies the analysis of such circuits. We mention them here in conjunction with Eqs. (25.16) and (25.17), in case you have already come across such circuits that you need to analyze in laboratory work.

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة