تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

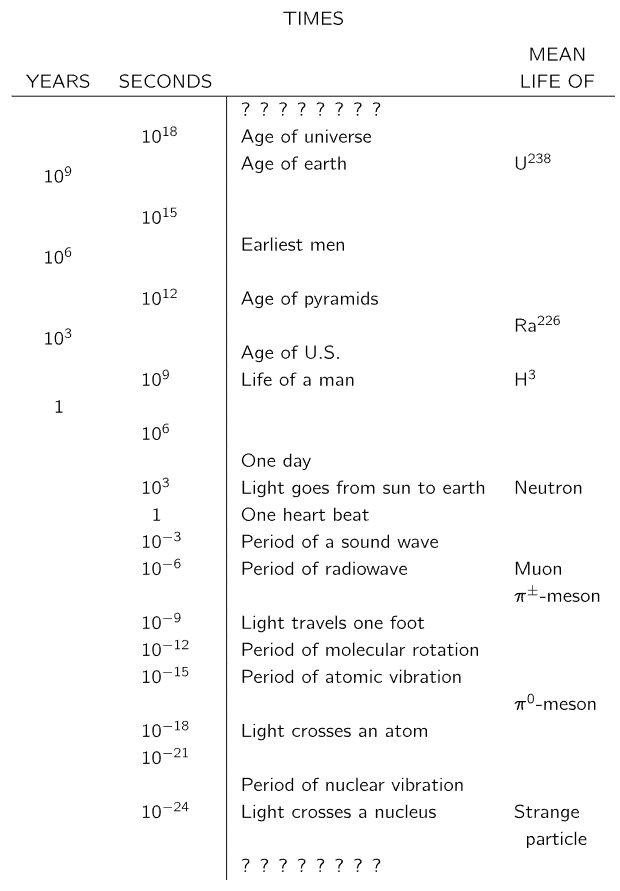

Long times

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 5

2024-01-27

1902

Let us now consider times longer than one day. Measurement of longer times is easy; we just count the days—so long as there is someone around to do the counting. First, we find that there is another natural periodicity: the year, about 365 days. We have also discovered that nature has sometimes provided a counter for the years, in the form of tree rings or river-bottom sediments. In some cases, we can use these natural time markers to determine the time which has passed since some early event.

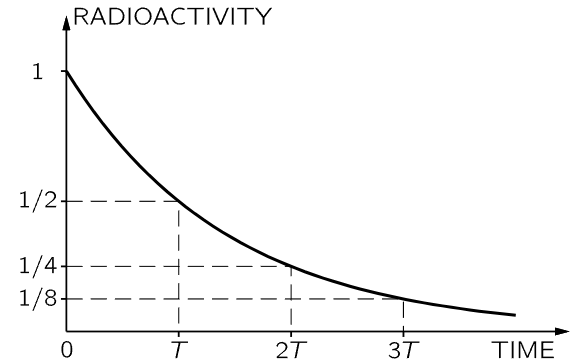

When we cannot count the years for the measurement of long times, we must look for other ways to measure. One of the most successful is the use of radioactive material as a “clock.” In this case we do not have a periodic occurrence, as for the day or the pendulum, but a new kind of “regularity.” We find that the radioactivity of a particular sample of material decreases by the same fraction for successive equal increases in its age. If we plot a graph of the radioactivity observed as a function of time (say in days), we obtain a curve like that shown in Fig. 5–3. We observe that if the radioactivity decreases to one-half in T days (called the “half-life”), then it decreases to one-quarter in another T days, and so on. In an arbitrary time interval t, there are t/T “half-lives,” and the fraction left after this time t is (1/2) t/T

Fig. 5–3. The decrease with time of radioactivity. The activity decreases by one-half in each “half-life,” T.

If we knew that a piece of material, say a piece of wood, had contained an amount A of radioactive material when it was formed, and we found out by a direct measurement that it now contains the amount B, we could compute the age of the object, t, by solving the equation

(1/2) t/T=B/A.

There are, fortunately, cases in which we can know the amount of radioactivity that was in an object when it was formed. We know, for example, that the carbon dioxide in the air contains a certain small fraction of the radioactive carbon isotope C14 (replenished continuously by the action of cosmic rays). If we measure the total carbon content of an object, we know that a certain fraction of that amount was originally the radioactive C14; we know, therefore, the starting amount A to use in the formula above. Carbon-14 has a half-life of 5000 years. By careful measurements we can measure the amount left after 20 half-lives or so and can therefore “date” organic objects which grew as long as 100,000 years ago.

We would like to know, and we think we do know, the life of still older things. Much of our knowledge is based on the measurements of other radioactive isotopes which have different half-lives. If we make measurements with an isotope with a longer half-life, then we are able to measure longer times. Uranium, for example, has an isotope whose half-life is about 109 years, so that if some material was formed with uranium in it 109 years ago, only half the uranium would remain today. When the uranium disintegrates, it changes into lead. Consider a piece of rock which was formed a long time ago in some chemical process. Lead, being of a chemical nature different from uranium, would appear in one part of the rock and uranium would appear in another part of the rock. The uranium and lead would be separate. If we look at that piece of rock today, where there should only be uranium, we will now find a certain fraction of uranium and a certain fraction of lead. By comparing these fractions, we can tell what percent of the uranium disappeared and changed into lead. By this method, the age of certain rocks has been determined to be several billion years. An extension of this method, not using particular rocks but looking at the uranium and lead in the oceans and using averages over the earth, has been used to determine (within the past few years) that the age of the earth itself is approximately 4.5 billion years.

It is encouraging that the age of the earth is found to be the same as the age of the meteorites which land on the earth, as determined by the uranium method. It appears that the earth was formed out of rocks floating in space, and that the meteorites are, quite likely, some of that material left over. At some time more than five billion years ago, the universe started. It is now believed that at least our part of the universe had its beginning about ten or twelve billion years ago. We do not know what happened before then. In fact, we may well ask again: Does the question make any sense? Does an earlier time have any meaning?

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء العامة

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء العامة

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)