Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Valence alternations

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P70-C5

2025-12-17

140

Valence alternations

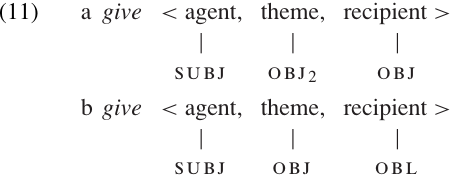

We have already seen that some verbs can be used in more than one way. In Semantic roles and Grammatical Relations, for example, we saw that the verb give occurs in two different clause patterns, as illustrated in (10). We can now see that these two uses of the verb involve the same semantic roles but a different assignment of Grammatical Relations, i.e. different sub categorization. This difference is represented in (11). The lexical entry for give must allow for both of these configurations.1

(10) a John gave Mary his old radio.

b John gave his old radio to Mary.

It is not difficult to find examples of other verbs with more than one possible valence. For example, in the following pairs of sentences we see the same verb used either with or without an object:

(12) a John has eaten his sandwich.

b John has eaten.

(13) a Bill is writing an autobiography.

b Bill is writing.

These sentences seem to show that eat and write can be either transitive or intransitive. However, the same kind of event is described in both patterns. Whenever you eat, something must get eaten; whenever you write, something must get written. So even in the (b) sentences, it seems reasonable to assume that the argument structure contains a patient, although we don’t know exactly what the patient is because it is not specified. It is even possible to refer to this unspecified patient, as illustrated in (14). The pronoun it in (14c) refers to the unspecified patient of (14b).

(14) a John: I feel hungry.

b Mary: Didn’t you eat before we left?

c John: Yes, but it wasn’t very substantial.

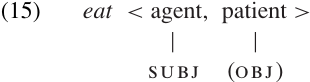

We might say that such verbs are semantically transitive, but differ from other transitive verbs in that they allow the patient argument to remain unexpressed. (For historical reasons, the pattern illustrated in (12b) and (13b) is sometimes called “unspecified object deletion.” A more precise term might be “unspecified patient suppression.”) We could represent the argument structure of these verbs as in (15), indicating that the patient may either be an OBJ, or be syntactically unexpressed:

But not all cases of variable transitivity can be treated in this way. Consider the following examples:

(16) a John is walking the dog.

b John is walking.

(17) a The sunshine is melting the snow.

b #The sunshine is melting.

c The snow is melting.

In example (16), it is not so clear that the same kind of event is described by both sentences. In (16b) John is definitely walking; but in (16a), while the dog is clearly walking, John could be riding a bicycle or roller-skating. Similarly, even though the string of words in sentence (17b) is a proper subset of sentence (17a), its meaning is quite different. Compare this example with (12) and (13) above. The sentence Bill is writing an autobiography clearly implies that Bill is writing; and John has eaten his sandwich clearly implies that John has eaten. However, sentence (17a) implies not (17b) but (17c).

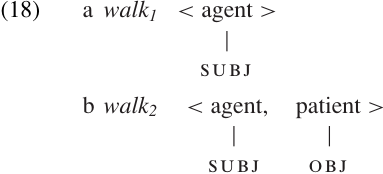

Thus, the variable transitivity in examples (16) and (17) seems to be of a different type from that in (12) and (13). For cases like (16) and (17), we might want to say that the verb simply has two different senses, each with its own argument structure (as illustrated in (18)), and both senses must be listed in the lexicon.

A number of languages have grammatical processes which, in effect, “change” an oblique argument into an object. The result is a change in the valence of the verb. This can be illustrated by the sentences in (19). In (19a), the beneficiary argument is expressed as an OBL, but in (19b) the beneficiary is expressed as an OBJ. So (19b) contains one more term than (19a), and the valence of the verb has increased from two to three; but there is no change in the number of semantic arguments. Grammatical operations which increase or decrease the valence of a verb are a topic of great interest to syntacticians.

(19) a John baked a cake for Mary.

b John baked Mary a cake.

1. The relationship between these two configurations can be expressed as a grammatical rule, since a number of other verbs allow the same kind of alternation. See Kroeger (2004, Constituent structure) for a detailed discussion of this alternation.

الاكثر قراءة في Sentences

الاكثر قراءة في Sentences

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)